Wajihah Hamid

I was in the airport waiting to fly back to Sydney from Melbourne when a friend texted me to ask how I was doing and if I was ok. I hadn’t read the news or seen the television yet, it was barely three hours after Friday prayers. Subsequently reading about it, my heart sank as I had some close family friends in New Zealand whom I knew attended Friday prayers in the main city mosques there. Upon learning that the perpetrator was from Australia, I began fearing for attacks on Muslims here. Just the week before I had made plans to attend Friday prayers in one of Sydney’s biggest mosques. It was in Sydney’s Lakemba mosque over three Ramadans and Eid celebrations that I observed and learnt about the nuances as well as significance of the mosque as a place of worship, and social gathering for Muslims in the West.

Despite coming from Singapore, where most neighbourhoods have a mosque and being a Muslim isn’t politically charged or perceived as a ‘problem’ as compared to being one in the West post 9/11, it was in Sydney where I experienced a special sense of serenity through attending various communal and Friday prayers regularly. It is also here where I experienced and learnt first-hand that the everyday normality of Muslims in Australia is fragile, as they have become the embodiment of the dangerous others.

The tragic incident in New Zealand’s Al-Noor mosque in March 2019 shows the frightening end point to which Islamophobia, misinformation and a basic lack of knowledge of Islam and Muslims and their practices can lead. Contemporary ideas, perceptions and thoughts of Islam and or Muslims, mosques, prayers and practices have been increasingly fed by social media. The suspected attacker, a 28-year-old Australian national had shared his motivations, inspirations and justified his killing of Muslims in his manifesto.

This, amongst other tragic events, has brought home the idea that Islamophobia is very real and deadly. To move forward beyond fear and hate, I appeal for the importance of developing a nuanced and deeper understanding of Islam, Muslims and mosques particularly through ordinary Muslims and their everyday practices, particularly within the Australian context.

For a long time, the building of mosques within the Australian context has been a cause of regular panics, where discourses around mosques tend to be racialized and stereotyped. Using his research on opposition to mosques in New South Wales, Dunn has identified that these discourses were then used by local politicians, residents, and media to culturally construct and define local (white Anglo-Australian) belonging, citizenship and community. Such discourses and tropes need to be challenged particularly now as the far right’s Islamophobic agenda has increasingly become normalized. Akbarzadeh has highlighted a positive correlation between the rise of far-right groups and the presence of anti-Islamic sentiments in Australia’s political mainstream.

In detailed ethnographic research on Islamophobia, Randa Abdel Fattah concretizes the above finding by showing how it has permeated everyday Australian life. In her thought provoking chapter on affective registers of Islamophobia, her participant Rita had shared ‘’I haven’t spoken to any Muslims, well, except you.’’ Rita subsequently shares that the local Australian media was her source of information on global events, Muslims and suspected terrorists. What is unnerving to me is that Rita too, like the alleged perpetrator behind the attacks in Christchurch, share the perception that Muslims are taking over. Through Rita’s narratives and the perpetrator’s manifesto it is apparent that they have not had much or any interaction with ordinary Muslims and their everyday practice of Islam.

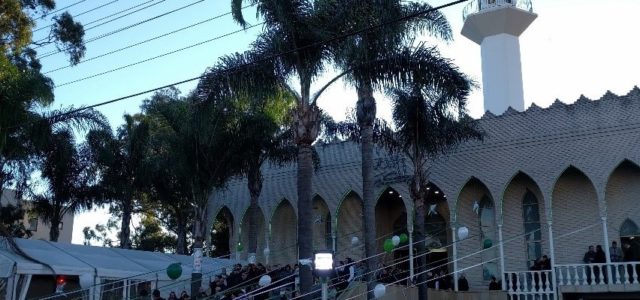

Much of what Australians have come to know of mosques, Muslims and Islam is often represented through masses of bodies prostrating together in ritual prayers. This stereotypical image has become one of the universal visual representations of Muslims. Lakemba mosque and the popular representation of the suburb too is no exception to this. Beyond it being chosen for visual footage, what is its significance to someone engaging in it? What does it mean to an ordinary everyday Muslim embodying this practice?

Using my research findings from Sydney’s Lakemba—home to the highest percentage of Muslims in Australia—my aim here is to bring to attention the importance of understanding Islam and Muslims in the West beyond pathology and stigma by focusing on Muslims’ everyday practices. Previously I have demystified Lakemba beyond its label as a ‘no-go zone’ and found it to be a space of refuge for Muslims, particularly women. While carrying out my ethnographic fieldwork there, the mosque usually emerged organically in conversations as one of the main motivations of residents for choosing the suburb or visiting Lakemba even after moving out. By understanding what Lakemba mosque—one of the largest mosques in Sydney—truly means to one of Lakemba’s Muslim residents, I highlight one of the ways everyday Muslim belonging is embodied and experienced there.

I feel Eid is complete if I go there to pray…

I feel Eid is complete if I go there to pray…

Latifa, a first-generation female Muslim migrant from India who at the point of interview had lived in Lakemba for six years, shared her experiences of attending communal Eid prayers in Lakemba mosque and the mosque being the main attraction to move to Lakemba and continue living there despite increasing negative stereotypes of the suburb.

‘Oh my God, we just wait for the day. We just wait for the day. I go very early morning so that we … otherwise you won’t get any space to stand in. It’s nice. Especially I want to go there because after the prayer we meet many friends. All the friends we made, maybe a year, two years before, we meet them there. We greet, we give salaam, and we do charity. And that day is very special. So, I feel Eid is complete only if I go to there to pray. Only if I go there [emphatically] … There are many different venues that are in for prayer, but still I feel happy only if I go to Lakemba Mosque… I’m going there (for six years). Only one time I went to other place, but I’m not happy on that day. I said, “No, no. From next time I want to go only Lakemba Mosque… That’s one of the main reasons, when we decide to live in Lakemba. [emphatically].’ (Latifa)

Latifa began sharing that the current stigma and pathology surrounding Muslims and Lakemba had an impact on their lives, drawing on her husband’s experience where a past job interviewer had negatively remarked about Lakemba. She shared with me saying ‘Our suburb is Lakemba, everybody looks up and down. It’s a really embarrassing moment [emphatically].’ However, she emphasised that despite such experiences, living close to the mosque and being able to attend communal prayers enables her to feel connected to Lakemba as a suburb and place of belonging. The Lakemba mosque anchors her in the local area, “That’s [the mosque] one of the main reasons, when we decide to live in Lakemba” [emphatically].

This sheds light on the way belonging is shaped and affected by the physically embodied experience of praying together congregationally in the Lakemba mosque, meeting old and new friends and sharing moments together. Through Latifa’s articulation above we are also presented with a glimpse of some of the ordinary and peaceful activities Muslims engage in in mosques in Australia.

Islamophobia and the killing spree which took place in the Al-Noor mosque did not come overnight and has been the result of anti-Muslim rhetoric of some political leaders and media agencies. While it now may seem that right wing extremism perhaps has succeeded in instilling fear against Muslims, it is imperative at this very moment to challenge the rhetoric by seeking to understand Muslims and Islam through ordinary Muslims, their everyday lives and practices. By understanding what attracts ordinary Muslims such as Latifa to the mosque, one is able to get a more balanced perspective of Islam, Muslims, and their ideas of belonging through everyday practices. My research has revealed that contrary to popular political rhetoric and media claims, ordinary Muslims in the West do feel a sense of belonging and such belongings are here to stay. More than ever, it is now urgent to acknowledge Muslims’ sense of belonging in the West, including Australia.

Wajihah Hamid is a PhD research scholar at the department of Sociology, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia. Carrying out ethnographic research, she examines the suburb of Lakemba in Sydney beyond the headlines using an intersectional approach. Her broader research interests include Muslims, belonging, Identity, the intersection between race and space, migration, and South Asian Diaspora.

IMAGE CREDIT: Author’s own photos