Dominic Davies

What do you think of when you hear the word ‘comics’? Most likely, Superman, Spider-Man, Batman, or another white, male, US superhero will come to mind. Perhaps you remember your childhood Beano or Tin Tin albums? Maybe you were once an avid reader of Charles Schultz’s Peanuts strips or even the UK’s ongoing science-fiction magazine 2000 AD? Or perhaps you still read ‘adult’ comics, such as Art Spiegelman’s Maus or Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home – though you might prefer to think of these as graphic novels or graphic memoirs, rather than comics per se?

Now, what do you think of when asked to consider the relationship between comics and ‘race’? Maybe you think again of Tin Tin, and Hergé’s notoriously racist depiction of Congolese Africans in Tin Tin au Congo? Maybe you are thinking of 2018’s re-boot of the Black Panther franchise, and the potentially – though debatably – emancipatory messages that this film contained? Just as likely, your mind may turn to the many offensive cartoons that have caused outrage across the US, Europe and Middle East in recent decades, from the controversial representations of the Prophet Mohammed by Denmark’s Jyllands-Posten and France’s Charlie Hebdo to the more recent and outwardly racist depiction of Serena Williams in Australia’s Herald Sun?

In this survey, comics and cartoons do not immediately suggest themselves as aligned with decolonising methodologies or debates. But where is the global South here? What are comics artist located in cities of the South up to in the twenty-first century, and does their work assert a more radical, decolonial perspective to and through this resurgent medium?

In a new book, Urban Comics: Infrastructure & the Global City in Contemporary Graphic Narratives, I look at the work of different comics artists and collectives working across five Southern cities (Cairo, Cape Town, New Orleans, Delhi and Beirut), as well as other urban spaces in the West Bank, Gaza, and along the US-Mexico border, to argue that yes, comics are engaged with a range of decolonial projects. In this effort, I join and contribute to a gradually growing geographic and conceptual decolonisation of comics studies. Shifting our geographic lens away from the Anglo-American world reveals that in fact, comics across the South are engaged in both their form and content with a radical revisioning of violent, neocolonial urban spaces. Moreover, these Southern artists are often connected to a range of radical urban social movements that seek to challenge racial and gender-based urban violence and to reclaim for marginalised populations a newly radical ‘right to the city’, as Henri Lefebvre first termed it.

The Egyptian Revolution of 2011 ignited an explosion of radical cultural production that centred on the massive occupations of, and protests in, Cairo’s Tahrir Square. Magdy El Shafee’s 2008 graphic novel, Metro, A Story of Cairo, anticipated these events, especially as they were routed through the reclamation of urban space. Meanwhile, Deena Mohamed’s webcomic about a female Muslim superhero, Qahera, raised and represented issues of gender violence and sexual harassment during the protests, creating through its multiple online issues an alternative vision of more socially and spatially just city spaces. These Egyptian comics have been both about and of the Revolution. Artists such as Ahmed Nady drew comics as protest banners in the space of Tahrir Square itself, while internationally-renowned graffiti practitioners such as Ganzeer have turned from their subversive street art to speculative comics in order to continue their critique of the oppressive constraints imposed by post-2011 Egypt’s counter-revolutionary urban violence.

In the Southern US city of New Orleans, the New Orleans Comics and Zine festival (NOCAZ) attempts not only to create a platform for a growing network of independent print publishers across the South, but also to open that network up to previously occluded voices. The artists included in this collective align their comics with New Orleans’ recent removal of its confederate monuments, and support the city’s local chapter of Black Lives Matter by creating, like Ahmed Nady, banners that protest the deaths of young black men at the hands of police and contributing the proceeds to the families of these victims. Meanwhile in South Africa, historian Koni Benson collaborated with the comics artists and brothers Nathan and André Trantraal to document the history and ongoing activism of women’s social movements organising in Crossroads, a township on the outskirts of Cape Town. Visualising continued calls for basic infrastructure services such as water, shelter and electricity that extend from apartheid into post-apartheid eras, this comics series – entitled Crossroads, after the community it represents – seeks to place the twenty-first-century activism of marginalised African women in a decolonised historical context.

Readers may be familiar with the ground-breaking work of the US comics journalist Joe Sacco, whose 1990s comics series Palestine pioneered a new field of politicised graphic narratives that sought to capture the voices and experiences of colonised subaltern populations. Much of the Southern work I have mentioned here takes inspiration from Sacco’s example. But this is no uni-directional, North-South movement, and Palestinian artists have themselves collaborated with other anti-colonial activist groups across the West Bank to realise the decolonial potential of the comics form.

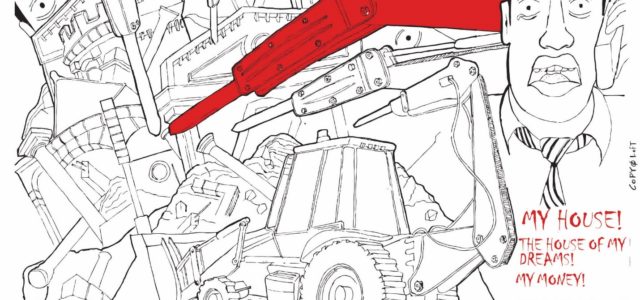

For example, the artist and architect Samir Harb has drawn comics for the collective Decolonizing Architecture, an architectural studio and art residency programme based in Beit Sahour, Palestine. As they outline in their book Architecture After Revolution, the collective incorporates the work of canonical decolonial writers such as Frantz Fanon into their methodologies. In a 2010 project and exhibition, Decolonizing Architecture explored the liminal legal space of the lines that were drawn in pen onto maps of the West Bank during the 1993 Oslo Accords. While these boundary lines organised the territory on either side of them into administrative units, the ink of the drawn line signified a thickness that, at the scale of 1:20,000, translated into more than 5 metres of actual geographic space. Harb’s comics for this exhibition documented the everyday activities of Palestinians who build in these interstitial zones in order to resist the spatial constrictions of the Israeli Occupation. They combined a right to the city narrative with a decolonial perspective in order to mount a challenge to the often violent, top-down urban planning regimes of settler colonial states.

Combining these examples with many others, Urban Comics shows how, in the global South especially, comics artists might be thought of as radical, cultural engineers. They use the graphic narrative form in innovative ways to draw up alternative urban plans that are aesthetically capable of capturing the informal, subversive rhythms of city life. Moreover, these artists are especially interested in linking up with local urban movements, bringing a decolonial perspective to bear on their activist and social justice impulses. The research included in Urban Comics tries to demonstrate a crucial need to reevaluate the potential of a medium that, though often at the centre of scandals around race and racism in Europe and the US, is in fact aligned with – and in many cases, an active contributor to – the often anti-racist and anti-patriarchal social movements that are working to rebuild more socially and spatially inclusive cities in and across the global South today.

Dominic Davies is a Lecturer in English at City, University of London. He holds a Dphil and British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowship from the University of Oxford, where he also established the Oxford Comics Network. He is the author of Imperial Infrastructure and Spatial Resistance in Colonial Literature, 1880-1930 (Peter Lang, 2017) and Urban Comics: Infrastructure & the Global City in Contemporary Graphic Narratives (Routledge, 2019). He has published a number of articles and book-chapters on topics relating to colonial and postcolonial literature and history, and he is the co-editor of Fighting Words: Fifteen Books that Shaped the Postcolonial World (Peter Lang, 2017) and Planned Violence: Post/Colonial Urban Infrastructure, Literature & Culture (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). He is currently co-editing a collection of essays entitled Documenting Trauma in Comics: Traumatic Pasts, Embodied Histories and Graphic Reportage (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

Image: Samir Harb