Lauren Johnson

The Sunbury Plantation House in Barbados; The Mourne Coubaril estate in Saint Lucia; the Maima-Seville Heritage Park in Jamaica – the list goes on. Representations of slavery on the plantation are a multiplicity in the Caribbean, but this limits the view of the West Indian’s existence, ultimately to a Western working subordinate.

Heritage is in many ways about preservation of the collective self and the past; but it should come as no surprise that accounts of history are subject to selection and distortion. In 2009, UNESCO placed the Maima-Seville Great House & Heritage Park in Jamaica on their list of World Heritage sites — the site is also regarded as an official ‘heritage’ site of Jamaica. Their reasoning: that the site bears testimony to “two distinct and now vanished cultures”; that it is a space where a “thorough exchange of different human values and ideals” took place; and that the site is “a perfect illustration” of “the daily life of both the slaves and the European elite.” These are the criteria by which the site is deemed to be worthy as a representation of Jamaican heritage. Already, a hierarchy is exacted here.

The park (a sugar plantation once active in the days of slavery) is composed of the plantation’s “Great House”, reconstructions of Taino huts and artefacts, and slave houses in which its purpose is to serve as a tourist site. The Great House (which overlooks the sugar cane fields) is used as a museum, displaying artefacts of the various cultural groups that resided on the island with the grounds harbouring replicas of the living quarters of the Amerindians and African slaves. To being with, these replications potentially leave the visitor with the most basic and inauthentic image of a people based on preconceived ideas circulated through popular media, which dangerously feeds into what are already widespread myths about Black heritage.

These historical reproductions reinforce the colonial distinctions of social and racial hierarchies during slavery. In UNESCO branding the area as an official site of Jamaican heritage, the Seville Heritage Park is a landscape where slavery and racism is commemorated, transformed and made sacred. With this display of land, the park is commercialised to reinforce the dominant “cultural” narrative of Jamaica’s past. Although, with the likes of tourism, it becomes difficult to assert whether this display of heritage is selected to repeat narratives of cultural dominance, all the while summoning the cultural power dynamics of the past between the West and the Caribbean through capitalism. This participates in forming cultural stigmas that are confined to this history.

While the plantation space has had a long history in the Caribbean dating back to the 17th century as a site of slave labour and economic profitability for those in power, this is not the only history for the islands. The issue is not that these narratives are damaging and therefore should not be showcased at all, but rather the fact that they become the primary form of representation for the heritage of the people that reside within. There are a multitude of other aspects that are part of the heritage of these islands – both tangible and intangible – that do not attract the same attention as these sites of slave activity and inequality do. Ultimately, what is at risk here is the integrity of those who are constantly reminded of this violent history. Not only in this capacity, but deeming this space a heritage site where its purpose is as a ploy for profit mirrors the same sentiment of the initial construction of the plantation site in its beginnings of exploitation across the Caribbean in the slave trade.

The Caribbean is no stranger to exoticism at the hands of tourist industries. In fact, they are a dominant source of income for its island economies, especially in Jamaica. There is a noted bias in the Caribbean where it is common for plantation houses to be deemed as heritage sites (Joliffe, 2015). Changes in the economy have meant that governments have turned their attention to tourism as a main source of income. As a result, many former slave owner’s plantations are widely sanctioned as heritage sites for the purpose of attracting tourists. Fair enough, UNESCO aims to educate, to reflect and encourage the teaching of a damaging past (much like the commemorations of the Holocaust), but there are only so many times that narratives of negativity should be repeated until they become the dominant association in a long history that Black heritage is associated with.

Culture in this case becomes more of a system of management. Upon consistently seeing these same images, the island’s cultural heritage remains stagnant as these repeated narratives of slavery and subordination are marketed to foreigners through the replications of the conditions of that time. Since an integral part of heritage is how it is understood and received by the public, Jamaica like many other islands in the Caribbean fall subject to a foreign gaze from a past (and still in some ways present) inferiority. That is not to say that tourism is the bane of all heritage sites used to showcase the history of a people, but rather a significant component in how a people and a place is received on a global scale, and its vital role in producing the discourses and narratives that are created with it.

It is for this reason that organisations like UNESCO play an important role in bringing national histories to the forefront. In certifying the Seville Heritage park as an exemplar of Jamaica’s heritage, part of the island’s cultural identity is legitimized through this body of authority. UNESCO (2009) reports that “Seville Heritage Park is illustrative of an environmental and societal evolution that is distinctly Caribbean,” which in itself poses a problem by confining West Indian identity to a history of slavery, and the concurrent coloniser/colonised relationship founded on the plantation. With West Indians portrayed as the colonised, the plantation site marks out the social divisions that once were and still are present in global hierarchies.

Local businesses and organisations also play a significant role in the matter as they have a close relationship with the heritage site and its construction which help determine how heritage is, and will be, communicated to the public. The Jamaica National Heritage Trust recently motioned for the Park to be Jamaica’s number one tourist site attraction – further prioritising the site’s potential for profitability over the protruding cultural assumptions of a colonial ideology rooted in Jamaica’s past. The funding from these more local management bodies (including the Tourism Product Development Company and the Spanish Jamaican Foundation) help determine how heritage is, and will be communicated to the public, thus holding the power to reveal and even conceal such knowledge.

The park and its landscape in its commemoration then becomes symbolic of the Jamaican people’s values in both their past and their present. For this site however, emphasis is placed on European influence and activity: the scale and cultivation of the landscape showing off the wealth of the English plantation owner. One must ask themselves whether this heritage site is for the Jamaican people as a stark reminder of their hardships or for the pride of the British? In any case, the site as an official representation of Jamaican heritage reproduces a narrative of slavery as cultural; Jamaican identity is reduced to the ploughing of sugar canes by slaves for the Spanish and English exportation of sugar as a cash crop. Yes, slavery is an inescapable part of the West Indian community’s collective memory and should rightfully be acknowledge in order to fuel progress, but West Indian identity should not be confined to this past to which in many cases heritage organisations ultimately legitimise in this way.

References

Jolliffe, L. (2015). Sugar, Heritage and Tourism in Transition. Bristol: Short Run Press.

Lauren N. Johnson is a freelance academic writer, interested in culture and people. She currently writes for online magazine, Society19UK.

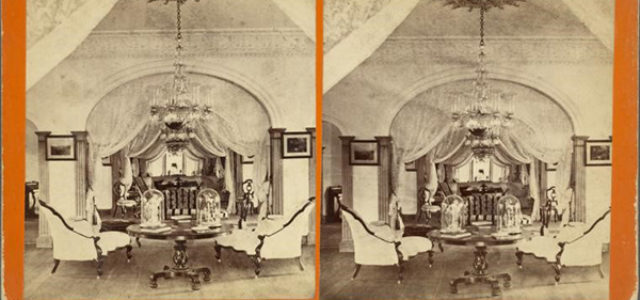

Image credit: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. (1865). Interior of Farley Hill, Barbados.