Marek Skovajsa

A recent English-language issue of the Czech SociologicalReview/ Sociologický časopis (2018, 54 [3]) features a symposium, Remembering Prague Spring 1968 (free to download), of which I was editor. In it thirteen sociologists, social theorists and political scientists recalled personal experiences relating to the ‘events’ of 1968 in Czechoslovakia and offered their thoughts on the significance of the Czechoslovak reform project. A sequel to this symposium is scheduled to appear in the same journal in the summer of 2019.

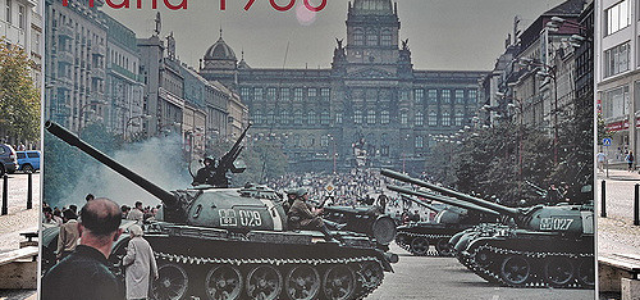

Was there ever a chance for a state-socialist system to become genuinely democratic? Many people wouldn’t think so, but others would say that this possibility seemed to be on the horizon in such historical moments as the Hungarian Uprising of 1956, the Prague Spring of 1968 or the Polish Solidarity movement of 1980. We will never know, as all these processes were prevented from running their full course by the brute force of the military and the police. The Czechoslovak attempt to establish ‘socialism with a human face’ was crushed by a Soviet-led military intervention on 21 August 1968.

If it perhaps enjoys a special place among the episodes of liberalisation of a state-socialist system, it is because it coincided and was connected through a dense network of mutual influences with other protest movements developing in many countries of the world. This international context makes it truly unique. But the Prague Spring wasn’t just a protest movement; it was an all-encompassing political and societal reform in the course of being formed. As Stephen Turner has argued in this Symposium, ‘this was not merely a protest: it was a collective political experience of the whole society, led by the state itself’ (page 467).

The complete defeat of the reformers and the hard-line nature of the ensuing neo-Stalinist regime in Czechoslovakia made the Prague Spring look like an irresponsible wager made by those naïve enough to believe that Communist authoritarianism could be humanised. That was the interpretation that prevailed in Czech society after 1989, when the leading catchwords of the day were ‘freedom’, ‘democracy’ and ‘market’, but certainly not ‘socialism’, no matter what face it might wear.

But history does not end. As the Czech Republic and other East Central European countries are approaching 30 years since the collapse of their Communist regimes, the story of their democratic and capitalist development is far from triumphant. Oligarchic state capture, populism and persistent economic weakness in comparison with Western Europe are impossible to ignore. It is against the backdrop of this crisis of the liberal-democratic-cum-capitalist project in East Central Europe, largely conceived of as a copycat version of simplified and decontextualised Western models (deemed universal), that alternative social visions of a progressive nature rooted in these countries’ historical experiences is worth a second look. Reconsidering them might be difficult and open to misinterpretation, but potentially rewarding, for, as Jacques Rupnik has commented, ‘if your aim is to imitate Western economic and political models you cease to be interesting for the West. And, more importantly: what if you are imitating a model in crisis?’ (page 441)

The objective of this symposium was to gather memories and reflections of the Prague Spring from sociologists and social theorists who were young adults or older at the time of these events (that is, who were born in 1950 or earlier). The intention was to make this material available to a wide readership, not to analyse it and certainly not to evaluate it. Sociologists and social theorists have written before about their experience of and their views on the events of 1968 (Sica and Turner 2005; Bhambra and Demir 2009). These and other books are in fact sharp analytical studies as well as valuable autobiographical testimony on what happened in 1968, but they contain few or no references to the Prague Spring. Our symposium was thus inspired by the idea of producing a collection of short texts by sociologists in which the Czechoslovak reform project would figure centrally both as the reference point for personal recollections and as the subject to be reflected on in terms of its significance then and now. These papers taken together form but one tiny piece in a large and rapidly growing mosaic of literature devoted to studying the 1968 period from a transnational perspective (see, e.g., Gildea, Mark and Warring 2013).

As far as the list of contributors is concerned, there was no intention to produce a representative sample in any geographical, political or other sense. It would certainly be a noteworthy project to create a similar collection of written reflections from Czech and Slovak academics and make them accessible in English. But this would no longer be feasible for sociology alone as the list of surviving Czech or Slovak sociologists who took part in the events is now very short. Conversely, if other disciplines were to be included, the project would become too broad. One important motive behind this symposium was to add the voices of scholars abroad to domestic Czech discussions of the subject of 1968, as these discussions tend to be rather inward looking.

Authors from two regions were invited to participate: from East Central Europe, because of the similar history and political developments, and from the global West, this latter group in order to provide them with an opportunity to extend the scope of their past reflections on the year 1968 to include the Prague Spring. Sociologists (and some philosophers and political scientists), most of them based in large Western countries, and most of whom had written on the subject of 1968 before, were invited to contribute. The final list of contributors was the product of the editor’s decisions about whom to invite but also of the varying non-response or refusal rates among the different categories of authors contacted. It is no accident that more than half of those who contributed are either émigrés from East Central Europe who live(d) in the West or Western authors who spent at least some part of their life in the East. But the focus on the West and Central Europe did indeed give rise to two of the lacunae: there are no authors from the ex-USSR or Russia and China, and no authors from the global South.

The third and most embarrassing lacuna is the absence of women among the contributors, with one notable exception – the Hungarian philosopher Ágnes Heller, who was one of the few intellectuals in the Eastern bloc to protest publicly against the Soviet invasion. It was not for a lack of trying on my part to get other female scholars on board that this imbalance came about. Among possible explanations, one seems particularly interesting, which is that the authors who accepted the invitation to contribute tended to see some positive meaning attached to the Czechoslovak reform project. From the viewpoint of women’s emancipation and the feminist movement, the Prague Spring wasn’t an internationally important event (Quiz question: how many female figures connected with 1968 in Czechoslovakia do you know?).

There were of course some moderately progressive developments in Czechoslovak state policies toward women and important feminist breakthroughs in the cultural sphere in the 1960s, but the outlook of most Communist reformers on the issues of gender and sexuality was conservative (Havelková 2009: 44). If the Prague Spring has only minor significance in the history of women’s rights and sexual liberation, feminist authors find little reason to discuss it.

The contributors were asked to write both an autobiographical account of how the Prague Spring resonated with them personally and their thoughts on its meaning viewed from the perspective of today. The autobiographical part of the proposal wasn’t misled by the unrealistic expectation that all the details the authors retrieved from their memory would not only be factually accurate but would also provide an undistorted picture of how they actually perceived the events in Czechoslovakia back then. Yet, even though it seems unavoidable that the autobiographical stories would show how the participants of 1968 have constructed the Prague Spring in their own memory in the time since and up until now, this does not mean their recollections must be disqualified for a lack of empirical validity. After all, the Czechoslovak reform process conforms surprisingly well to William Outhwaite’s observation that 1968 ‘is a year defined by process rather than outcome, inviting a focus on its phenomenology rather than an analysis of its material causes and consequences. In other words, the memory, true or false, is to a substantial extent the reality.’ (2009: 176)

The weight the authors attach to their personal experience of the Prague Spring varies widely, from ‘my most important politically relevant memory of 1968’ (Hans Joas, Symposium: page 449) to ex-post realisations that something of interest had been going on in 1968 also in Czechoslovakia. But that the Prague Spring had strong autobiographical relevance for contributors was not a necessary precondition for their readiness to ponder its significance. Like other historical moments, the Czechoslovak reform process has been many times interpreted, misinterpreted, and reinterpreted, adapted to widely disparate contexts and instrumentalised for different political purposes, as Maud Bracke has shown in reference to the French left’s appropriation of the Prague Spring (Bracke 2008). The diverging interpretations presented in this symposium indicate that the Czechoslovak democratisation experiment was and remains a subject of lively controversy. Yet, perhaps most of all, the papers provide proof that even on its 50th anniversary the Prague Spring continues to generate hope and disappointment. Although there does not seem to be any successor project around in the world at the moment, this does not mean there won’t be one in the future.

The year 2018 was a very busy one for the Czechs in terms of commemorating the most important milestones in their political history. Consistent with the nature of this history, the anniversaries that were marked – a series of important years ending in an 8 (e.g. 1968) – are a mixed bag of glorious and inglorious moments: the establishment of the first independent and modern Czechoslovak state in 1918 and the dismemberment of this state after the Munich Pact in 1938; the 1948 coup staged by the Czechoslovak Communist Party, which made the country into a Soviet satellite; and, last but not least, the Prague Spring. The wheels of the celebratory machinery were turning at full speed for most of this year, especially in connection with the centenary of Czechoslovakia. But if any of the years among these key moments in Czech history can aspire to international significance, it is the year 1968, the year of the Czechoslovak Spring.

References:

Bhambra, Gurminder K. and Ipek Demir (eds.) (2009). 1968 in Retrospect: History, Theory, Alterity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bracke, Maud (2008). ‘French Responses to the Prague Spring: Connections, (Mis)perception and Appropriation.’ Europe-Asia Studies 60 (10): 1735-1747.

Gildea, Robert, James Mark, and Anette Warring (eds.) (2013). Europe’s 1968: Voices of Revolt. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Havelková, Hana (2009). ‘Dreifache Enteignung und eine unterbrochene Chance: Der „Prager Frühling“ und die Frauen-und Geschlechterdiskussion in der Tschechoslowakei.’ L’Homme 20 (2): 31-50.

Outhwaite, William (2009). ‘Conclusion: When Did 1968 End?’ Pp. 175 – 183 in G.K. Bhambra and I. Demir (eds.). 1968 in Retrospect: History, Theory, Alterity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sica, A. and S. Turner (eds.) (2005). The Disobedient Generation: Social Theorists in the Sixties. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Marek Skovajsa teaches social theory and the history of the social sciences at the Faculty of Humanities, Charles University, in Prague. He was for ten years the editor of the Czech Sociological Review published by the Institute of Sociology, Czech Academy of Sciences. His research interests include the history of sociology, sociological theories of culture, and political culture and democracy. Among his publications are: Sociology in the Czech Republic (with J. Balon, Palgrave 2017), Structures of Meaning: Culture in Contemporary Social Theory (Slon, 2013).

The Czech sociological journal Sociologický časopis / Czech Sociological Review began publishing some of its issues in English in the early 1990s (a sign of the new optimistic times after the regime change of 1989). The following authors contributed to the symposium, Remembering Prague Spring 1968: Johann P. Arnason (Iceland/Czech Republic), Richard Flacks (USA), John A. Hall (Canada), Ágnes Heller (Hungary), Hans Joas (Germany), György Lengyel (Hungary), William Outhwaite (UK), Jacques Rupnik (France/Czech Republic), Ilja Šrubař (Germany/Czech Republic), Vladimir Tismaneanu and Marius Stan (USA/Romania), Stephen Turner (USA), Jerzy J. Wiatr (Poland).

Image: FaceMePLS CC BY 2.0