Helen Goulden

Meritocracy, on the face of it, would initially seem to be one of the least worst ways of formulating a hierarchy. It is based on the assumption that those who extend their efforts and apply their intelligence – whoever they are – are worthy and deserving of taking their varying senior positions in the professions, industry and public office. Yet, hierarchies of any kind, whether they are of intelligence, or strength or wealth are problematic – they assume there is more below than above and require a form of ‘legitimacy’ contract of authority from the many to the few in order to be stable.

Michael Young, author of the satirical book Rise of the Meritcracy, published in 1958, wanted to see the creation of a society where all people were able to pursue their talents and succeed in fulfilling their potential as human beings. But, he predicted that a mature meritocracy would lead to calcification of a new ruling elite, one more pernicious than had gone before, because of this notion of it being ‘deserved’ – and so there being a justification for it being held on to – and that people would ultimately turn away from that new class, against the meritocratic elite; after feeling shut out and devalued. He also predicted this would lead to a surge in populism, rising nationalism – and a rebellion led by women.

But, putting meritocracy in perspective today is more complex than ever before.

The idea that if you work hard and you’ve got a head on your shoulders, you will be successful has persisted as a publicly told story. But it is as debilitating a message as it is empowering. Moreover, trends on social mobility do not support that kind of story for many people.

Debates about meritocracy have become overly confined to the education system. While there’s no doubt that the quality and extent of an education has a material and often lifetime impact on an individual, there are two massive problems with boxing our conversations about meritocracy into one of schooling for attainment. Getting on in life is only partly about your classroom experiences. If you’re hungry, generally not eating well, living in a household that is experiencing sustained financial stress and all of the challenges that come with that, you don’t do as well at school. Equally, if you’re in low paid work, you’re still not that likely to progress out of it, no matter how hard you work. Though increases in the national minimum wage have had positive benefits, precarious, insecure work has increased. In employment, collective bargaining has decreased across the board and, in education, technology and access to it is also having a considerable impact on equality of education and skills development; without forgetting that automation is spelling trouble in both spheres.

The geographic polarisation of our local economies across the country, even how the choices that are made in planning our transport infrastructure, also directly affect your chances of being able to find good work and an affordable place to live. One in seven tenants in the UK is paying more than half of their income in rent. This has got nothing to do with hard work and intelligence but with structural inequalities and geographic imbalances. All of the top ten places where you see the greatest social mobility are cities. Most of the places where you see the lowest social mobility are not.

As such, any abstracted conversation about education being the driver of a meritocratic society, without attending to place, and place-based policies and systems, our ageing towns, the geographic distribution of jobs, housing, the decentralisation of power, and attention to the successive sedimentary layers of history that lie unevenly across all of different towns, cities and places across the UK, means we are only having half a conversation.

The issue of geography may well lie at the heart of the debate about meritocracy. The new elite born of a meritocracy could be argued as being as much about the marriage of social norms and networks to accessing resources in certain localities across the country, as it is of a marriage of two IQ’s. Of course, geography lies at the heart of the underlying sore of discontent that unfolded as a result of the EU referendum.

We must change the terms of the debate about meritocracy and ask questions like: what has merit? What do we value?

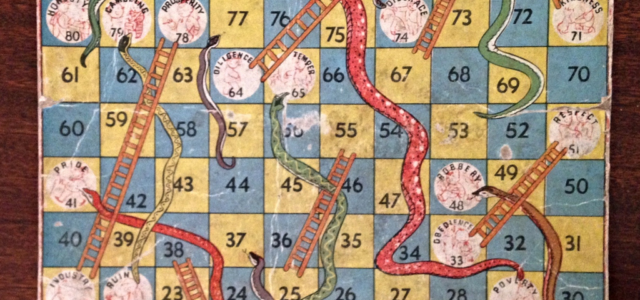

The meritocratic equation, as set out by Michael Young’s satire, is IQ + Effort. This is peculiarly valueless and amoral given it doesn’t speak of purpose, or intent, or effort with a sense of responsibility. The unit of focus is also individual so, subsequently, the effort is individual and so too are the rewards.

The mobilisation of an early meritocracy in and of itself has positive benefits enough on the general well-being of a broader base of the population — an increasing flow of access to education, rising incomes for more households, increased health care and so on. We saw all this in the 20th Century and the attendant rise in social mobility. But, those days are over. Could it not be possible to now live in society where we evaluate people, not only according to their intelligence and their education but according to their kindliness and their courage, their imagination, sympathy and generosity?

This approach might seem alien to the structure today of our 21st Century economy but when you start to look more closely, it doesn’t look quite so fluffy. Parts of our economy and society are heading this way already.

You only need listen to people in communities across the country talk about their experiences to know that some feel highly devalued, that they have no merit; that we’re failing as a national community. The statistics on loneliness, social isolation and poor mental health speak for themselves. These are the consequential losses of a more individualistic society, where we have categorised and rewarded some individual’s success and work as having merit, and others as having none. At the same time, data on mass extinctions, loss of marine life, increasing global temperatures show that we humans are in real trouble.

Yet, in among all of this, there are efforts underway to redress what is given merit and what is valued – and very real efforts try and quantify and legitimise measuring what matters to us. Take for example the development of new measures such as National Well-being Indices, Quality of Life Surveys, the Thriving Places Index in recent years. They each attempt to capture not individual, but community well-being.

Community-led movements and social forms of innovation, built on creativity and kindness for others, are also increasingly finding their voice and a following. This shouldn’t be surprising. In communities where people know each other a bit more, you see less crime; you see reduced hospital admissions; you see higher degrees of capability to respond and adapt to unpredicted events. Connected communities seem to make us a bit happier as individuals.

In business, we are also seeing change in this direction too. The UK has been quietly growing a particularly vibrant and advanced social economy; with rising numbers of community-owned businesses, co-operatives mission led business and social enterprises that are aligning revenue generation with social and environmental purpose and broadening ownership of value in an economic system. This is supported by a growing flow of social finance that only will support businesses that can demonstrate real, positive and lasting contributions to communities and society.

Returning to our education system, the ability to collaborate with others, to be able to empathise and communicate with lots of different kinds of people, to be creative and solve problems together are attributes and competencies that are making their way to the fore of school curriculums – albeit slowly. This trend responds to the inevitable material needs driven by automation and an ageing population, but the wider benefits and the urge to ‘do good’ is there.

Ultimately, there are many examples of how we can value different things; changing what is deemed to have merit. There is clearly a growing appetite amongst the public for readdressing what we merit beyond individual well-being, status and limited classifications of success. This is more than a utopian ideal, or a debate about education.

Helen Goulden is Chief Executive of the Young Foundation

Image: Pru Mitchell CC BY 2.0.