Sara Wheeler

“Families with different surnames may be asked questions to establish their relationship. Thank you” (The Home Office)

It was with this tweet, issued on the 1st August 2018, that the UK Home Office sparked a debate on twitter, about the diversity of naming practices in Britain, and how sharing the same ‘surname’ within families is increasingly uncommon.

As Finch has previously noted, the Anglo-Saxon naming formula of forename(s) and surnames is dominant legally as well as culturally in contemporary Britain – despite not necessarily reflecting the naming customs of other cultural groups now settled in the UK. However, as the debate around this assumption by the Home Office has highlighted, there is an indigenous language community within ‘Britain’, who are as much at odds with this custom as migrant groups – the Welsh-speaking community.

This issue, and a variety of other aspects which demonstrate the chasm between Welsh and English names, are the subject of my recent publication in the field of onomastics – the study of names and naming.

This is an interesting time to be studying Welsh naming practices, because as Wales gains greater political independence and confidence, the Welsh community appear to be doing all kinds of interesting and creative things with regards to personal names; these patterns can give fascinating insights into emerging and transforming identities and senses of belonging.

The re-emergence of the patronymic naming practice in Wales

In response to the Home Office tweet, Plaid Cymru assembly member/ MP Hywel Williams responded by tweeting on the 2nd August 2018:

“Wholly unacceptable. Having different surnames is not some bureaucratic problem. My wife is Davies – she’s not an add-on to me. My children are Hywel – a pattern becoming more common in Wales as we shed practices enforced on us during industrialization”.

Here, Hywel Williams is referring to the patronymic naming practice, in which individuals were identified (or ‘placed’ socially) by their relationships, chiefly in relation to their father, so ‘Mab’, ‘ab’, or ‘ap’ (son of) and ‘Ferch’ (daughter of). Thus Garmon, who was the son of Garth, would have been ‘Garmon ap Garth’.

The patronymic naming practice was common throughout Europe, including England. However, ‘settled surnames’ had mainly been adopted in England between the 12th and 15th centuries, largely in a response to the needs of growing towns and bureaucracy. Meanwhile, Wales was less affected by urban influences and pressures as there were few towns and much of the population was unaffected by English social practice. Thus the ancient naming-system had continued until much later.

However, the Acts of Union of 1536 and 1542 removed the Welsh language from all official domains in favour of English. The Act of 1536 specifically had a ‘language clause’, which basically stated that if Welsh people wanted to prosper, they cease speaking any language other than English. Thus, following the Acts of Union, Welsh families found it necessary to take a single ‘surname’, which would be a better match for this linguistic and cultural context which privileged ‘English’ customs. Following on from the patronymic tradition, they tended to choose surnames from within their pedigree, for example the forename of their father or paternal grandfather. Modern surnames demonstrate how Anglicization of ‘ap’/ ‘ab’ meaning ‘son of’, were incorporated into the formation of the new names; for example, Hywel ab Owen, became Howell Bowen.

While these newly formed surnames, which became settled and used in the way that they are today, eventually replaced the traditional patronymic system, there was, according to Moore, an observable ‘intermediate stage’, when it was common to use a Christian name followed by an unfixed surname, the latter of which would often be determined by first names of males in the family: “The great Methodist leader John Elias (who died 1841) was the son of Elias Jones, who was the son of John Elias”.

There was also an allied phenomenon of alternative fixed surnames:

“David Morgan Huw of Trefilan, Cardiganshire, who was also known as ‘David Morgan’” (Moore).

This second phenomenon is particularly interesting in the contemporary context, as there appears to be a recent trend towards a naming practice whereby a first and second name are given, as well as a surname, at birth. However, the use of the surname is discouraged and it is becoming increasingly common to observe people using just their first two names. For example, singer, political activist and past president of Plaid Cymru, Dafydd Iwan, is not commonly known as ‘Dafydd Iwan Jones’, which is in fact his full name.

Whilst this could be perceived as a stage name, given his profession, discussions with my students and others from the Welsh-speaking community have revealed that this appears to be a growing trend and a source of much pride. This is despite the problems it can cause, for example, with delivery people for student halls, who express frustration that students don’t use surnames.

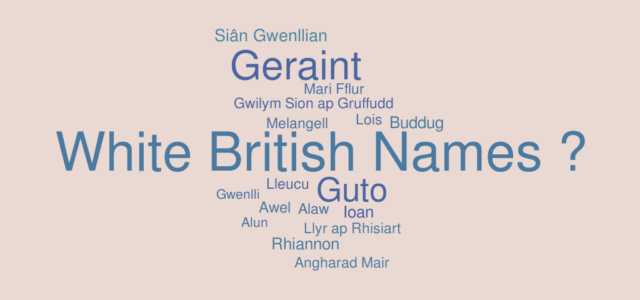

Geraint, Guto and Ioan – White British Names?

Another aspect of Welsh naming practices, which has hit the headlines in recent weeks, is the fact that many Welsh names emanate from the Welsh language, and thus are very different from English names. Welshman Geraint Thomas won the Tour de France this year, but his victory in Wales was somewhat overshadowed by incredulity over the fact that BBC reporters seemed completely unable to pronounce his forename. However, as well as anger, this has prompted some humorous and creative responses, including a video on how to pronounce ‘Geraint’.

This activity all came on the heels of the furore on twitter regarding Welsh politician Guto Bebb’s name, as tweets focussed on belittling his name, rather than why he had resigned his position. This particular incident within social media has been seen by some as another example of racism towards Welsh people. This has been a common theme in recent months, following the comments of Rod Liddle in relation to the debate around the re-naming of the ‘Second Severn Crossing’.

Much of the current research in relation to names and naming focusses on migrant experiences. Wykes, makes a distinction between ‘White British Names’ and ‘foreign’ names, claiming that ‘White British Names’ afford their bearers ‘White British Privilege’. However, I would raise the question whether names such as ‘Geraint’ and ‘Guto’ are ‘White British’ – if so, they do not seem to be bringing their bearers much ‘White British Privilege’. Furthermore, the return to the patronymic practice in Wales, and the emerging other expressions of Welshness, will undoubtedly cause non-privileged complications at border control.

In her article, Wykes refers to a series of ‘microaggressions’ towards the migrant participants of her research, which she likens to the ones discussed by Nigatu, which include people asking things like “No, where are you really from?” However, I would point out that these kind of ‘microaggressions’ are common towards Welsh people, for example being accused of only speaking Welsh when English people walk into the pub, or being asked “But do you actually speak Welsh”.

In terms of Welsh names, in my recent article I point out the kinds of ‘microaggressions’ which have been experienced by Welsh celebrities, for example Ioan Gruffudd, which have included:

“Your last name is completely preposterous, I don’t know what’s going on over there”

In a previous article, I have described similar ‘microaggressions’ which I myself have experienced towards my forename, ‘Sara’, for which my parents chose the Welsh pronunciation ‘Særæ’ (transcribed in phonetics), as in Lara (Antipova from Dr Zhivago). Reactions have included assumptions that I am ‘Trying to be posh’ – despite this simply being my given name.

Furthermore, in another article, I have discussed the fact that, the kinds of incidents which Wykes cites as being ‘microaggressions’ towards migrants, and, conversely the privileges they describe upon changing their names, may in fact be misperceptions. For example, Wykes states that Kayla Brackenbury (pseudonymn), who had a Zimbabwean maiden name, which was then replaced by her ‘White British’ married name, reported that her credit file had improved, because she had a changed:

“I’m getting…offered, more credit…just compared to {what I was offered} as Kayla Manyika”.

However, when I got married and swapped the surname ‘Edwards’, which indexes for Welsh, but probably also for ‘White British’, for the surname ‘Wheeler’, which undoubtedly indexes as ‘White British’ and also ‘English’, my car insurance premium went down. Whilst I might have been tempted to perceived this as ‘White British Privilege’, or in this case ‘White English Privilege’, a discussion with the insurance salesperson revealed that it was actually because insurance companies see married people as not being such ‘risk takers’ – which personally I felt was debatable, though a welcome perception given that it meant I’d pay less to insure my car.

Conclusion

There have been many incidents recently, including the emotive issue of renaming the ‘Second Severn Crossing’, which have raised the issue of ‘Othering’ Welsh people, and even whether it is possible for Welsh people to be the subject of ‘racism’. I think what I have highlighted here is that Welsh people certainly are the subject of negative and prejudiced attentions, particularly with regards to our language and culture; an important part of this sense of identity and sense of belonging are our personal and place names, and the debates regarding them highlight the fractures within the indigenous communities, which collectively are referred to as ‘British’. Unpacking these issues may help explain current unease with the term ‘British’ and help understand current and future tensions within the United Kingdom.

Sara Louise Wheeler is a lecturer with Y Coleg Cymraeg Cenedlaethol (National Welsh Medium College) based at Bangor University, North Wales. She tweets at @SerenSiwenna