Christian Garland

“Don’t start from the good old things, but the bad new ones” (Brecht)

Benjamin’s maxim that nothing that has ever happened can be regarded as lost for history [1] is important to keep in mind when reflecting on the events of May 1968 in France, and especially in 2018, its 50th anniversary. However, this moment risks becoming a nostalgic memorial in our own urgent present of 2018, as it becomes more and more distant and removed by the passage of time, and direct generational experience.

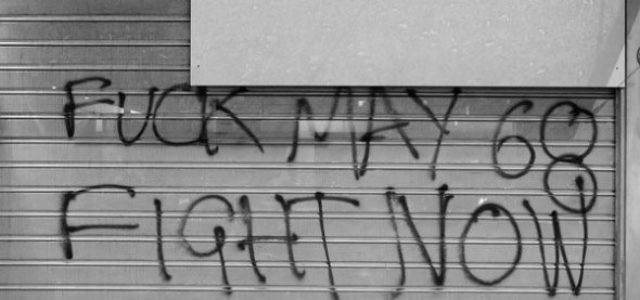

Indeed, the 2008 graffiti from Athens, illustrated above, , is not meant as a dismissal of May ’68, but is an effort to articulate the necessity of contesting the present. It is an assertion of Jetztzeit, the time-of-the-now, to make sense of why it is the way it is and might yet be different. This unwritten future is one certainly imbued with the knowledge of May’68 and its significance, and it is for this reason the Athens graffiti seeks to disrupt any false closure and implicit end of history narrative. These frequently underlies most post-dating of concepts and none more so than revolution and the notion of radical socially progressive change.

2011 not without good reason, was compared to 1968, since there did at last seem to be some approximation of radical social and political change: The Arab Spring, the Indignados in Spain, rolling wide-scale if not general strikes and mass protests across continental Europe combusting into riots, the riots in London combusting into riots across the whole of England that August, and Occupy Wall Street that October spreading across the whole of the US and the world. However, some six years later we are faced by a tide of reaction in which never has the future looked more uncertain or insecure. This paper aims to contribute to ‘blasting open’ the confined present, and indeed ‘fighting now’.

May 68 has been accurately described as “The uprising which overtook France 50 years ago and fermented a social, sexual and cultural revolution, despite its political failure. Arguments about its repercussions have been raging ever since.” Indeed, it should be kept in mind by those who understand that the events in France of that May-June half a century ago and the social forces which animated them continue in our urgent present of 2018. A decade ago in 2008 – the 40th anniversary of the notorious evenments then-French President Nicolas Sarkozy also understood their lasting significance and long-term effects when he declared “May ’68’s heritage must be liquidated once and for all”, that heritage being in large part every socially progressive gain of the second half of the twentieth century as well as the early twenty-first century. Sarkozy’s reactionary anxiety over May ’68, as Julian Bourg has noted was because it “symbolizes the opening of an era, and unstoppable transformations that cannot be contained.”

The uncertainty with which the 2018 50th anniversary of May ’68 was greeted by the ‘post-political’ post-’68 centrist Emmanuel Macron should come as no surprise. Macron, at 40 and born in the late-70s, is the first French president to be too young to remember the evenments first-hand, having taken place almost a decade before his birth. Indeed, the uncertainty of the state over how to ‘celebrate’ a series of subversive and cataclysmic events aimed at nothing less than revolution poses a central and recurrent problem: how best to banish the historical memory of something which whilst being unique and specific to a particular time and place, is also an example of the “temporal index” (2) of hope and contestation of the present? The French state has always been aware of the significance of May ’68 and regardless of incumbent government, aware of the existential threat the events posed at the time, and the potential threat these embody now, being the wholesale calling into question of the form life takes in late capitalist society.

The ‘commemoration’ of the events which were, and are, unique in modern society, arguably with only one other significant equal: the ‘Hot Autumn’ in Italy the following year (1969), and the recurrent series of events in that country culminating in 1977, inevitably face being made into a curiosity of retrospective kitsch if they are viewed as having no bearing on the present from which they are viewed. It is in this sense that Benjamin warns us in the Theses on the Philosophy of History

“The true image of the past flits by. The past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant it is recognized and is never seen again. For every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably” (3).

In 2018 we are faced by a world in crisis, in which the reactionary backlash against neoliberalism remains in the ascendant. This backlash against neoliberalism being however, thoroughly contrived and not in fact against neoliberalism at all but presenting itself in such terms. The populist turn of the last three years mobilizes hopes and fears from above along with a conservative and retroactive ideological narrative presenting itself as ‘radical’. The left – such as it is – remains at present in its own state of crisis unable to convincingly counter and replace these reactionary forces. However it should be added that what is being referred to is the ‘orthodox, or standard’ left, not all those on ‘the left’ per se.

This piece aims to define the importance of May ’68 for now and the future, and against “The affirmation of the present, the existent, which aims to recognise a vision of the past, but only one in its own image imputed with its own conditions and demands” (4). As such, this vision of the past is ‘history from above’, in which the victors – the ruling class and its political faction in control of the state – record events as they would like them to be remembered, their true nature forgotten – history not being what has made the past and also brought us to our present moment. This is the ‘bad faith’ of ideology seeking to refract historical events from the vantage point of the present, in which it is claimed that they are either of little significance and can be safely ignored, and/or they are irrelevant to how the world is now. This erroneous vision of the past and present is one in which the existing dismal ‘state-of-things’ is not only upheld as inevitable and immutable, but eternalized and sanctified.

To be sure, the effort to counter such a vision of ‘history from above’ should not be mistaken as an ahistorical and nostalgic retrospective. First hand participant Mitchell Abidor notes,“to think you could recreate May ’68 in a vacuum is arrant nonsense” (5). The backward-looking effort to simply recreate and repeat a specific series of events is also not something those serious about their importance or how they relate to our urgent present can or should countenance. The ‘official’ version of May ’68 is one underscored by a distinct unease over what is the signature event of the 1960s and 1970s, a time in which everything about the form society took and how life is not lived (6) was called into question. May ’68 did indeed call the entire form of social life into question and none more so than how material existence itself is reproduced, and embodied in ‘work’. Capitalism was paralyzed by a spontaneous general wildcat strike across all sectors of the economy involving at its height, 10 million people. The riots in Paris and across France that year, no less than the poetic graffiti, are a permanent reminder that supposed ‘contentment’ with consumer capitalism and its everyday banalities, was a lie.

The response to the upheavals and revolts of the 60s and 70s in Europe and the US by Capital and its economic and social represeantatives across all of the countries formerly comprising the ‘First World’, was to re-group and as far as possible re-align and restructure production relations to make such direct contestation close to impossible, a task it should be said that has been largely successful. The past four decades of neoliberal globalization are not without serious problems however. The late-2010s bear witness to this, not least in a resurgent far-right and in its ‘alt-right’ garb bogusly claiming to be the historical reckoning of neoliberal globalization. Benjamin as early as 1930, noted with disarming premonition, “Behind every fascism is a failed revolution”, and the reaction ‘against’ globalized free market capitalism can also be seen in such terms.

May ’68 retains its historical power because in this fleeting moment at the beginning of the late Twentieth Century is crystallized the consciousness that revolt against the existing dismal ‘state-of-things’ is both necessary and possible, and that life as it is not lived day-to-day is only bearable at all because we are aware that it could be different, that this present state-of-things is not ‘given’ and is not invulnerable. It is my contention that ‘our side’ – the forces of opposition and resistance – must take account of the urgent present, and how past momentous events led to it, and in so doing that we might grasp the mettle of the Jetztzeit, the ‘time-of-the-now’, toward an unwritten and redemptive future.

References

(1) Benjamin, W. (1940) Theses on the Philosophy of History, Thesis II in Illuminations (London: Pimlico) p.245

(2) Benjamin, Thesis V p.247

(3) Garland, C. ‘A Secret Heliotropism of May ‘68: Historical Postponement, Mimesis, and Nostalgia’ pps.3-16 in Movements in Time: Revolution, Social Justice and Times of Change, Part 1. Protest Time Lawrence C.A, & Churn, N. eds. (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing) p. 3

(4) Abidor, M. (2018) ‘May Made me: An Oral History of the 1968 Uprising in France’, Talk and book launch, May 15 2018, Houseman’s London

(5) This is a paraphrase of Ferdinand Kurnberger, quoted By Theodor Adorno at the start of Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life (London: Verso) p.19

Christian Garland teaches precariously at Queen Mary, University of London and has degrees in Philosophy and Politics from the University of East Anglia (UEA) and Social and Political Thought from the University of Sussex. He has research interests including Marx and Frankfurt School Critical Theory especially applying this to the rapidly changing nature of work and how this can be said to embody social relations of atomization and individualization: the re-composition and restructuring of the Capital-labour relation itself. A version of this paper was presented at the conference F*ck May 68, Fight Now: Exploring the Uses of the Radical Past from 1968 to Today, June 8, 2018, Department of History, University of Liverpool.