Dominic O’Sullivan

In 2015, the Australian Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition appointed a Referendum Council. The Australian Constitution can be amended only by public referendum. The Council’s task was to consult widely among indigenous Australia and recommend the form of a Constitutional amendment to ‘recognise’ indigenous peoples. Successful constitutional referendums are rare in Australia. 2017 marks the 50th anniversary of one of the few to succeed; that which allowed indigenous people to be counted in a national population census and which allowed the Commonwealth government to make laws for their benefit. In 2017, the Government and Opposition anticipated indigenous Australia settling for a modest and ideally inconsequential recognition of prior occupancy.

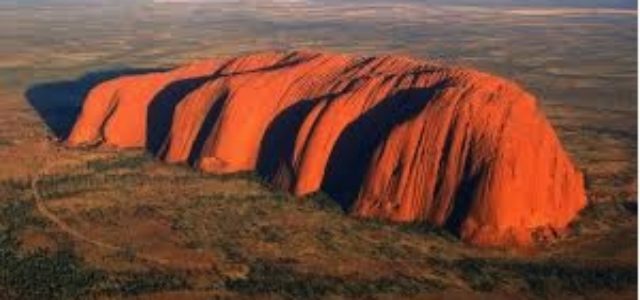

The Referendum Council’s final recommendations to the Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition will be made on 30 June. The communiqué released at the conclusion of the Council’s consultation process shows that indigenous Australian expectations are, in fact, neither modest nor inconsequential. The Uluru Statement from the Heart proposes a constitutionally guaranteed indigenous voice ‘to Parliament’ and recognition of indigenous sovereignty as a spiritual notion; the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return hither to be reunited with our ancestors. This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown… With substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this ancient sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood.

The form that this ‘fuller expression’ of nationhood might take is still to be worked out. It will be politically difficult and controversial. The idea that indigenous people ought to share, as indigenous, in the sovereign whole is sharply contested. The Uluru Statement’s translation into nationally acceptable, yet still politically worthwhile amendments to the Constitution, depends on indigenous Australia convincing a suspicious public that its proposals will strengthen liberal democracy, not threaten it.

There is an influential assimilationist narrative once expressed in a Liberal party election campaign theme song that will have to be undone: ‘Son you’re Australian, that’s enough for anyone to be’. People will have to accept that between the state and the family there are indigenous nations that are worth preserving and that indigenous political voices strengthen democracy by their guaranteed presence.

The Uluru Statement argues for an indigenous ‘voice to parliament’ rather than a voice in parliament. There would be some kind of elected indigenous body that would have powers to advise the Parliament, perhaps scrutinise legislation or question public officials in the style of a Senate Estimates Committee. This differs from the New Zealand practice where Maori have, since 1867, been guaranteed the right to elect their own members of Parliament. However, the two paths to secure democratic voice are compatible and one can use the same liberal democratic arguments to support one or both.

Guaranteed and substantive political participation allows indigenous peoples to engage in public affairs as members of the sovereign citizenry, rather than as subjects of a hopefully benevolent state, waiting for others to recognise their presence. Guaranteed participation recognises that an egalitarian justice, alone, cannot consider indigenous claims to culture, language, collective resource ownership, or just terms of association between indigenous peoples and public institutions.

Liberal democracy can tend to encourage conformity but it can also protect difference. It can propose the protection of all not just some people’s rights to participate in public affairs. The ideal of a strong democracy, with checks on political power, is strengthened when everybody can participate. Guaranteed participation overcomes the otherwise inevitable distance between parliaments and the indigenous peoples for whom they presume to make policy. Active participation in the political life of the community fosters a positive conception of citizenship and stable political order.

Citizenship is not best understood as a body of entitlements; but as a body of political capacities. Including the capacity to re-shape the neo-colonial context under which contemporary politics occurs; where the indigenous citizen is not always ‘one who deliberates’ according to Aristotle’s ideal. One will know that a post-colonial present has arrived when political agency is equally distributed; when indigenous people can use their political agency to secure their cultural traditions, secure the opportunity to derive material and spiritual sustenance from their lands and participate in public affairs as distinctively indigenous members of the Commonwealth. In these ways, foundations are laid for indigenous sovereignties to coexist with that of the Crown, as the Uluru Statement proposes. Just as importantly, foundations are also laid for the reconfiguration of Crown sovereignty. An authority that is legitimised by being inclusive of all citizens. The state is not then, a Leviathan-like sovereign, ruling exclusively and without contestation.

The argument for structured and guaranteed inclusion is consistent with the United Nations’ Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Declaration affirms a two-fold right to self-determination. Firstly, a distinctive indigenous political authority in and over their own affairs and secondly, the right to participate in public affairs in ways that are culturally meaningful and politically focused on the ways in which indigenous peoples themselves choose to enjoy national citizenship.

Self-determination gives effect to the conception of sovereignty that the Uluru Statement proposes. It responds to the state’s history as an institution of omnipresent coercive and constraining political power. It recognises that politics and relative power relationships are not constant. They are not fixed in the functions they maintain, nor in the ways that they distribute power. The state has no need always to include or exclude the same people.

The Declaration proposes an inclusive democratic state where indigenous peoples must be guaranteed substantive voice and which serves the state’s integrative function, but in ways that are not assimilationist and which balance the state’s authority with the explicit expectation that indigenous peoples are able to consider the distinctive ways in which they wish to enjoy national citizenship, with implications for democracy and the meaning of indigenous belonging to the state.

While liberal democracy does presume a strong common national identity, the pursuit of that objective through an imposed cultural homogeneity and violent assimilationist policies is profoundly illiberal and has not succeeded. Indigenous people do not wish to be drawn into a singular non-indigenous whole. Indigenous politics is not, therefore, instinctively inclined towards liberal democracy as a path to self-determination. However, the UN Declaration is an alternative, unique and potentially far-reaching statement of liberal possibility that supports inclusive sovereignty. It imagines a comprehensive transformation from liberal democracy’s capacity to exclude to its capacity for plural recognition.

Indigenous peoples reasonably expect to be able to occupy distinct culturally contextualised spaces in a state that has emerged over territories that they never ceded and whose institutions have developed without regard for indigenous presence.

The Uluru Statement, supported by the inclusive liberalism of the UN Declaration, invites the juxtaposition of liberal and indigenous political theories to create a standard of justice against which institutional arrangements can be measured. The intellectual alignment of these distinctive accounts of the source of political authority may provide a new and inclusive political language for thinking about and responding to indigenous claims to live as indigenous citizens of a genuine Commonwealth. A commonwealth that can admit extant rights of prior occupancy, most especially the right to exist as distinct peoples, in ways that can do not interfere with the liberal rights of other citizens. Extant rights mean that an exclusive state cannot presume the right to define political agendas and entitlements, compromise the right to culture, or exclude people from opportunities to participate in public decision-making.

Recognising that sovereignty is inclusive, and neither absolute nor incontestable, means that all citizens must engage with theories of power and authority that are equipped to support cohesion and stability. The ultimate purpose is to change the indigenous affairs narrative from one of victimhood to one where people can live in equality and dignity.

Political values and expectations are culturally framed and for indigenous peoples they are responsive to colonial context. Liberal politics is a politics of freedom. However, freedom is not an abstract concept. It is present or it is elusive in the different contexts of people’s everyday lives. Its meaning must come from somewhere and for indigenous peoples colonialism’s logic was to curtail freedom. If freedom is a liberal objective that belongs equally to all people the state must lose its neo-colonial character. It is, then, a reasonable liberal objective to re-configure the state to ensure that indigenous peoples are a part of it, both individually and collectively, and enjoy the opportunity to influence its values, purpose and form. That form could be an indigenous voice to parliament, in parliament or perhaps even both. However, for either to succeed the Australian public will need to be convinced that what is proposed is not a separatist fracturing of the body politic, but an inclusive measure that strengthens liberal democratic values and practice.

Dominic O’Sullivan is Associate Professor of Political Science at Charles Sturt University. He has more than 55 publications, including six previous books, most recently, Indigenous health: power, politics and citizenship (Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2015) and Indigeneity: a politics of potential – Australia, Fiji and New Zealand (Bristol: Policy Press, 2017).