Kalpana Kannabiran

A 2015 report of PEN International opens with the following lines: “In India today it is surprisingly easy to silence people with whom you disagree. An overlapping network of vague, overbroad laws and a corrupt and inefficient justice system have given rise to an environment in which speech can be quickly censored…This is a shameful state of affairs for the world’s largest democracy.” Indeed it is, but there is more to this story. I will attempt in this short essay to undertake a brief journey into the past – to recover the memory of history at a time when history is in peril; and reflect on our present predicament.

The 1960 film from Universal Studios, Spartacus based on a novel by Howard Fast tells the story of a slave rebellion against the Roman Republic in the first century BC led by the gladiator Spartacus. The most memorable scene in the film shows the Roman general promising freedom to recaptured slaves if they put Spartacus forward. Kirk Douglas as Spartacus steps forward: “I am Spartacus” – he is quickly followed by every one of the slaves present. This scene has over the years become iconic especially in times when repressive state regimes work with lists of persons who are singled out, identified, profiled, framed and criminalised for their dissent.

The question of academic freedom, imperilled today by the rise to state power of the Hindu Right in India, throws up several urgent questions for our consideration. There are also several parts to academic freedom that require opening out: the right to question, the right to know, the freedom of inquiry, the right to dissent and the full acknowledgement of academic endeavour as a practice of politics. At its core, it is a defense of rigorous scholarship, of uninhibited creative expression that is transgressive by definition, and of the open classroom that allows for a flow of ideas and disagreements. There is also the vital link to education – higher education in particular – that academic freedom is tied to: the institutional structures of HE, the freedom of association for all campus communities, and the right to the freedom of expression without fear of punitive action either within the protocols of HE (assessments, hiring practices, admission policies etc), or through the abdication of institutional governance to the repressive apparatus of the state.

Using state power to disembowel autonomy of universities and institutes, and using political power and governmental machinery to delegitimise the gains of social sciences, humanities and the sciences in favour of obscurantism in a new parade each day of the emperor in his new clothes, is by far the biggest assault we have seen on academic freedoms, and one that will have far reaching consequences for our collective futures. In recognition of the fact that resistance against authoritarian and oppressive regimes in post-colonial India has inevitably found its most stunning expressions on university campuses, with education, knowledge production, dissent and critical thinking interlocked in social and political thought, there are renewed efforts to harness campuses in the service of the state — through mob assaults, administrative arbitrariness, hiring practices, curtailment of financial subsidies in higher education, sudden and drastic changes in admisssion policies and criminalising robust debates on campuses. But also, importantly, through a narrow bureaucratisation of higher education that proceeds on a truncated distortion of knowledge and intellectual pursuit in terms of census driven immediate, measurable returns, delegitimising the pursuit of history, philosophy, literature and explorations of the seamlessness of knowledge and life, their interconnections and their essentially transgressive, irreducible character.

Dissent, which lies at the core of even a minimalist idea of academic freedom, is in this new era, constructed as “incitement to violence” and a “threat to national security” (with institutions being co-opted into the ring), opens the doors to state and mob violence that has “been incited.” The undermining of dissent, free speech and academic freedom is triggered through this construction of expression as incitement. Violence, raw violence itself, now decriminalised, subserves the upholding of “national honour” (now synonymous with security of the state) and is outsourced to anyone with a capacity for violence as pastime – these are our self-proclaimed “patriots.” This is the rule of law in what we believe to be (and what the PEN report describes as) “the world’s largest democracy.” The only credential check for acting in the name of the state is the limitless capacity for physical and verbal violence, and menacing conduct – this violence can today legitimately be used just about anywhere. There is no institution that guarantees protection to persons in custody despite evidence of torture and assault, as police, armies and a servile media collude with perpetrators of this ugly violence that has neither name nor knows any limit. Justitia stands blindfolded holding scales that tilt dangerously on the side of gross injustice, sponsored violence and organised misrule. We have known and seen this treatment of political dissidents in the past and have resisted it – it is marked now by its frightening spread and escalation through mobs on the street and the complete co-optation of the mass media with very few brave exceptions.

Academic freedom and free speech, both are now matters of life, death and liberty, like never before – victim to the cataclysmic shift in the framing of higher education by those that rule: educate, agitate, organise, in the seventieth year of India’s independence are replaced with indoctrinate, terrorise, criminalise.

There is a proliferation of names on lists and an accumulation of lists that travel seamlessly between proctorial boards, intelligence agencies, fringe groups, organised gangs in professional garb and goons on the prowl on the streets of our cities. You are damned if you are in custody. You are damned if you are not in custody. Fear stalks the streets and homes and universities – and yet, the voice of reason persists despite blocking news of protests, complicities with this unlawful exercise of power within institutions, brazen profiling, criminal intimidation, fabrication of evidence and direct incitement to violence and communal profiling on TV channels – “the country wants to know, my viewers also want to know” is the opening line of the anchor’s intimidation on camera, and the scholar-academic who speaks truth to power, because of the challenge she poses to authoritarian rule, is target. We can scarcely forget the proliferation of the moral police in the academy — within institutions of higher education — who have crawled out of the woodworks to assert that everything is normal and the trouble is the work of the “foreign hand” – Marx, Pakistan, the West… We are back to where we began our struggles for fundamental freedoms and democratic rights in India in the early to mid-nineteen seventies, but we have lost ground in an unprecedented fashion.

Why have universities come to occupy centre-stage? It might be useful to look at the triggers. University campuses shall not be ‘a part apart’ (to echo Dr. Ambedkar). This is the crux of the cascading resistance within campuses. What has thrown universities (and institutions of higher education in India) into crisis in the past two years, it cannot be forgotten, are questions raised by dalit students on the hanging of Afzal Guru (convicted in the Parliament attack case), discussions on Kashmir, the death penalty and discrimination on the basis of caste and religion: that is evident in the creation of agraharas [the brahmin quarters] and velivadas [the ‘untouchable’ hamlets], and in the conflict around consumption of beef on campuses in an Ambedkarite era.

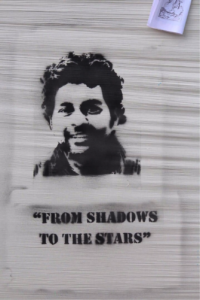

It was in fact this organising effort by the Ambedkar Students’ Association in 2015 led by Rohith Vemula that spiralled into a confrontation with students from the BJP students’ wing, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, the direct involvement of politicians and central ministers belonging to the ruling BJP, and a deeply complicit university administration. Interrogating their expulsion from the hostel, Rohith and four others camped on the streets of the campus that they named the ‘Velivada’, calling out deeply entrenched forms of caste discrimination and untouchability practices on the university campus. It was from the velivada in the University of Hyderabad that Rohith walked to a friend’s hostel room to hang himself on 17 January 2016. To quote from his suicide note, he was travelling “From shadows to the stars.” And beef-terror against Dalits and Muslims has now ripped through the country as never before, the eruptions on campuses signalling the onset of targetted violence and murder by lynch mobs on the streets.

At another level, the past couple of decades especially have seen the rise of Dalit movements and the large entry of Dalit and Adivasi students into universities. We also witness the rising resistance of Muslim students to deeply troubling targetted violence and deep-seated discrimination in the aftermath of the rise of Hindutva politics and government. The gender question has never been stronger and more complex than it is in this moment of churning – with women and LGBTQ persons confronting a misogynist, masculinist, stridently patriarchal gender order steered by majoritarian politics. These students possessed of the spirit of the constitution enter university campuses hoping that these spaces will nurture the power of questioning, and help promote the Article 17 spirit – the annihilation of caste and discrimination. But what they find is that the university is a conflicted space — negotiations around political dissent and free speech intersect with unequal gender and caste orders and hierarchical pedagogic practice. A cogent critique of the ways in which caste is taught in classrooms interlinks with caste as experience and the larger right to political dissent and free speech, with the figure of Dr. Ambedkar as the torchbearer of this renewed sensibility.

It is this constellation that is very new in the campus movements we witness today. The different resonances of azaadi (freedom) within university campuses, borrowing from older traditions of resistance for azaadi in Kashmir and in feminist movements, have rocked the foundations of the dominant, authoritarian, majoritarian community that is in control of the governance of the university, the state outside, and the streets – repression, arbitrary rule, the dismantling of institutions (indeed of the constitution itself) untrammelled powers to the police within and outside campuses and murder on the streets with the guarantee of impunity are the single method of rule to stem the tide of dissent.

This is also the time for us to recall shards of our engagements with free speech on the Indian subcontinent over the past century – to spin the historical record back into view. The accusation of sedition is not new. The facts of ‘incitement to violence,’ ‘clear and present danger,’ “persecution”[1] and marketplaces of a different order of ideas are perhaps constitutive of speech in colonial contexts, where there is little evidence that seditious speech was “chilled” by repressive legislation. Writers demonstrated again and yet again to the colonial government that “one man’s vulgarity is another’s lyric”[2] — whether it had to do with obscenity or with the brazen challenge of colonial rule. Speeches by “itinerant seditious orators,”[3]pamphlets, newspapers, poetry, stories, arms, ammunition (sometimes carried back and forth by “malcontent emigrants”[4])) and address lists of informers strapped the extreme right and the extreme left together in the term “revolutionary” and pitted them against the state/monarch, challenging the Sovereign. There are significant inversions in the conflations as they spread out across the borders of the partitioned sub-continent after 1947 and notable ruptures.

Sedition trials in independent India saw the imprisonment of poets and writers, especially those from radical left movements in the 1970s. Then, as now, universities were at the centre of the resistance to authoritarianism. However, in the present conflagration, majoritarian, dominant caste hate speech, the hallmark of three decades since the 1990s has gone largely unattended by courts with technologies of cyber communication harnessed in largely unregulated ways, not to speak of murder on the streets of free thinking intellectuals. The apparent seamlessness in jurisprudence and governmental action – the persistence of impunity — that straddles colonial and post-colonial contexts on the sub-continent is troubling. And yet, free speech on the Indian sub-continent has had a history that is somewhat more complex and layered than is evident from the legend of incidents of state and mob censorship that the PEN report recounts.

It will take a long time to undo this damage, but authoritarian rule will be defeated by the sheer grit of non-violent resistance — it always has been. And when that happens, there will be a remembrance of another kind — of those who stood unwavering to provide “freedom’s shade” (to echo Anis Kidwai).

Notes:

1. Gordon, Gregory S. Hate Speech and Persecution: A Contextual Approach, Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law, volume 46, no.2, March 2013, 303-373.

2. Justice Harlen in Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971). See also Golash, Deirdre (2010). ed. Freedom of Expression in a Diverse World (AMINTAPHIL: The Philosophical Foundations of Law and Justice, volume 3) Springer. Ebook.

3. Sedition Committee (1918). Report. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing, p. 139.

4. Sedition Committee (1918). Report. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing, p. 153.

Kalpana Kannabiran is a feminist sociologist and legal researcher and currently Professor and Director, Council for Social Development, Hyderabad, India. Her research focuses on the intersection between law, sociology and gender studies – examining caste, disability, indigenous rights and free speech in particular. The title of this article is taken from Niharendu Dutt Majumdar v. The Emperor, 43 Criminal Law Journal 1942, 504.

Images: Sannaki Munna. Main image – Radhika Vemula, Rohith Vermula’s mother addressing a gathering in Chennai after his death 2016.