Robin Mann and Steve Fenton

The results of the EU referendum in the United Kingdom came just in time to add some comments to our newly published book, Nation Class and Resentment: the politics of national identity in England Scotland and Wales. In these comments, we claimed the results tended to confirm some principal arguments we had advanced. We wrote of Scotland and Wales too, but on England we argued that a certain “resentful nationalism” was growing in strength and playing a new part in English and British politics. It was grounded partly in the discontents of the working class population, and embraced opposition to immigration, a dislike of multiculturalism and political correctness, as well as a distrust of politics and politicians. There is a matching, if less strident, English nationalism in sections of the middle and upper classes, and some of these voices were heard during the campaign. Since sending off our typescript and the present we have had time to think more about class, English national identity and resentment – and its relationship to new populist discourses, and the Leave vote in the EU referendum.

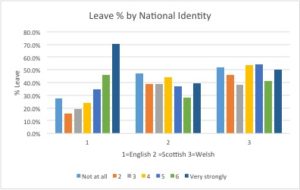

To what extent was voting leave in the EU referendum being driven by the rise of English resentful nationalism described in our book? To examine this we can look at the post-EU referendum wave of the British Election Study carried out between 24th June and 4th July 2016. The survey, based on a sample of some 10,000 people, asks the question of how people voted in the EU referendum and includes a question on strongly people feel about their national identity. The following table compares the percentage of the Leave vote in each of the three nations by English, Scottish and Welsh identity, and the results are quite striking.

The table indicates a relationship between the referendum vote and English identity, and an association between voting to leave and feeling very strongly English. Equally, we find some of the lowest proportions of Leave voters are amongst people in England reporting a weaker sense of English identity. It is possible that amongst those reporting weaker senses of English identity are higher proportions of non-whites, migrants and people of migrant parentage. It also supports the view that liberals and progressives in England are more reticent in their expressions of English identity.

In Scotland, by contrast, we see a different pattern whereby the proportion of leave voters is lower amongst those with a stronger sense of Scottish identity. In Wales, there is no obvious link between strength of Welsh identity and voting leave. So although England and Wales voted in similar proportions to vote leave as a whole, there appears to be a difference in how voting leave related to English and Welsh identities respectively.

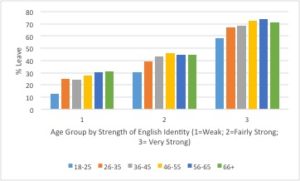

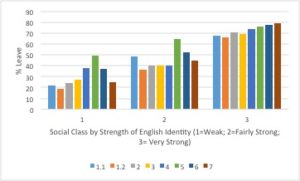

Analysis of the referendum vote has emphasised how older populations, people vulnerable to poverty and with fewer educational qualifications, as well as those living in economically disadvantaged areas were more likely to vote to leave the EU. But looking at the following two tables it is noteworthy that the association between feeling ‘very strongly English’ and voting Leave holds for all age groups and social classes. Whereas young people overall voted by a large margin to remain in the EU, we can see that 57.9% of 18-25 and 67.4% of 26-35 year olds with a very strong sense of English identity voted leave.

We do see that younger people who feel strongly English are a little less likely to vote leave than their older counterparts. We also find higher proportions of leave voters with weaker senses of English identity in the working classes – especially lower supervisory (NS-SEC 5). Still it remains that a very strong sense of Englishness appears to provide a basis support for leave across divisions of age and class. If we consider this on top of the existing evidence that support for UKIP and hostility to immigration are related to how English a person feels, then there is a strong case for arguing that the dominant expression of English identity is a resentful one. So why then did English nationalist resentment described come to form a basis for support to leave the EU? To understand this we need to consider how people’s sense of English nationhood has evolved.

The modern roots of English nationhood lie with the English upper and governing class which dominated the Parliament of England at the end of the seventeenth century. Politically, Englishness preceded Britishness, and a sense of English statehood and the “English people” preceded the British Empire. With the creation of Great Britain, Englishness became partly submerged in Britishness and British identity – associated with empire – took on an elevated position. But English identity did not go away. A form of political Englishness re-emerged at the end of the nineteenth century represented by a growing number of conservatives and liberals – often described as “Little Englanders” – who saw the efforts put into empire to be at the expense of domestic growth and prosperity. It also found explicit expression in Enoch Powell who, in his 1968 “Rivers of Blood” speech, fused the antiquated English class structure with a white racial English identity. Moreover Ben Wellings has argued that English nationalism, far from being absent, was “hidden” within the Eurosceptic wing of the Conservative Party. But not before the demise of Britishness symbolised by the welfare state and industry, as well as the declining support for the British Labour party amongst working class people, would the conditions be created for nationalist and populist parties of different kinds to succeed in UK elections.

The success of the “taking back control” slogan adopted by the Leave campaign is that it appeals to the nationalist sentiments of different classes and groups whose sense of identity is, at the same time, derived from different roots, and has a different tone. Thus explaining the leave vote lies, at least in part, with the Janus-faced character of English nationalism which appeals to concerns about immigration and foreign engagements, sovereignty and to traditional social values; as well as to elite interests in the idea of an open global Britain, both of which hark back to the British empire and a rather grand view on England’s place in the world.

Whether, and for how long, such a coalition might be sustained is open to question. If there is one thing that is clear it is that free movements of trade, i.e. economic globalisation, and movement of people are inextricably linked. This was evident both during the period of empire and subsequent post-Second World War immigration from the former commonwealth, as well as with the EU and free movement of labour. As we write, the UK government is already lowering public expectations on lowering immigration after Brexit. So it is hard to see how future global economic arrangements would allay popular grievances about nation and country and, for this reason, it is unlike that resentful nationalism will lose its appeal any time soon.

What prospects then for a progressive English nationalism? Evidence and scholarship tells us that liberals and the political left in England are not especially enamoured by English identity. In contrast, there is a progressive nationalism in Scotland which is available for liberals and for the left to draw on. Whether or not remain voters in Scotland turn toward an independent Scotland as an avenue for the pursuit of progressive politics is a matter of great debate presently. There is also a progressive Welsh nationalism but it is comparatively weak and it is a weakness which pushes Wales towards the England pattern. Nevertheless, the stronger remain vote in Scotland, especially amongst those most economically insecure, does show that the politics of resentment may be challenged when ordinary people are provided with a viable progressive alternative.

Notes:

(1) English Identity derived from seven point scale from Not At All English (1) to Very Strongly English (7): Weak (1-4); Fairly Strong (5-6); and Very Strong (7).

(2) NS-SEC Social Classes: 1.1 (Employers in Large Organisations and Higher Managerial); 1.2 (Higher Professional Occupations); 2 (Lower professional and managerial and higher supervisory; 3 (Intermediate Occupations); 4 (Employers in small organisations and own account workers); 5 Lower supervisory and technical occupations; 6 Semi-routine occupations; 7 Routine occupations.

Robin Mann is Senior Lecturer in Sociology at Bangor University, UK and a member of the Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research, Data and Methods (WISERD). Steve Fenton is Professor Emeritus of Sociology at the University of Bristol, UK and is a member of Bristol’s Centre for the Study of Ethnicity and Citizenship.

Image: ‘House decorated with England flags during the 2010 World cup finals’. By User Rept0n1x at Wikimedia Commons