Caroline Schlaufer

The Policy Briefing section of Discover Society is provided in collaboration with the journal Policy & Politics. The section is curated by Sarah Brown.

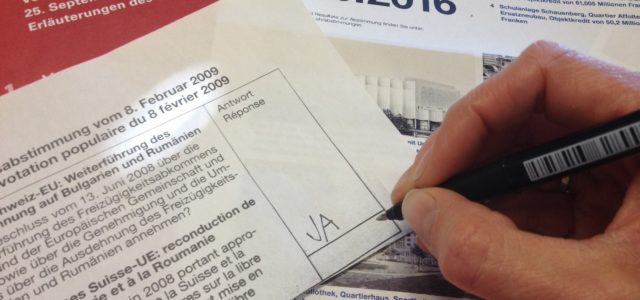

Referendums are increasingly used worldwide to allow citizens to directly decide about important policy issues. However, there is growing concern about whether citizens are properly informed when they make their choice in these usually complex referendum questions. For example, many commentators and editorials have argued in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum that facts and scientific evidence was politicised and not correctly used during the referendum campaign. Citizens, so it is argued, had made their decisions based on twisted facts.

However, in the context of a referendum campaign, facts, data and scientific evidence are always used politically. In other word, politicians, interest groups and governments always select those findings and data that fit their position and interpret scientific evidence in accordance with their political conviction. So yes, scientific evidence is politicized in referendum campaigns, but is this necessarily a bad thing? Based on the findings of a multiyear research project on the political use of scientific evidence in Swiss direct-democratic campaigns, I argue that scientific evidence, even when politically used, has the potential to enrich a referendum campaign in several ways.

Firstly, argumentation that contains scientific evidence focuses on policy and not on politics. By providing information on a policy in question the political use of evidence may, thus, enrich the content of a campaign. However, in order to do so, scientific evidence must contain policy-relevant information on the policy measures debated. This may be in the form of insights on potential outcomes or constraints of policy implementation, or by illustrating important context factors.

In my recent Policy & Politics article Global evidence in local debates: the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in Swiss direct-democratic debates on school policy, I argue that not all scientific studies used in policy debates may do so. In the article, I compare the political use of different studies in Swiss referendum campaigns in the field of education. It is one study that is predominantly used in the campaigns: the PISA study, a ranking of test results of 15-year-old students in reading, mathematics and science conducted by the Organization for Economic Development and Co-operation (OECD) every three years. In the examined referendum campaigns, PISA is used by both sides to argue in favour of, or against, a wide range of different policy measures. However, rankings such as PISA (and arguably also other statistical and monitoring data that do not analyse causality between policy measures and desirable policy outcomes) fail to provide information on the specific referendum questions. In contrast, scientific evidence that closely analyses the policy measures in question, such as policy evaluations, contributes to the content of the campaigns and have a potential to inform citizens on the referendum questions.

Whether the political use of evidence really can inform voters about the policy measure at stake and, eventually, contribute to a more informed campaign not only depends on what types of studies are used but also on how evidence is used. It is important to understand that when politicians use scientific evidence to influence opinions in the highly politicised context of a referendum campaign they do not present just data and numbers. Rather, they tell a story to voters and use evidence to make this story more convincing. Such stories usually first describe a problem (often caused by a villain) to then present their own solution as the happy ending.

The story of Brexit advocates, for example, presents high immigration as a severe problem caused by a villainous EU that can only be solved by leaving the EU. Evidence can be used in relation to different elements of a story to make the story more convincing – what I call the narrative uses of evidence. Most frequently, evidence is used in connection with the problem the referendum is supposed to solve: numbers and data are stated to demonstrate how severe a problem really is. Also frequent is the use of evidence to present a particular solution as effective and superior to the solution proposed by opponents. In both of these cases the evidence used in the referendum debate may offer relevant information to voters such as: is the policy problem really relevant to me or to society? Is the proposed solution apt to address the problem?

Secondly, in my Evaluation and Program Planning article, ‘The contribution of evaluations to the discourse quality of newspaper content’, I show how the political use of evidence may also lead to a higher quality of argumentation. Let me explain. When politicians use scientific evidence in their argumentation, they not only focus on content, they also use less offensive and disrespectful language. In addition, statements supported by scientific evidence usually contain a justification why voters should vote for or against a referendum question, which, unfortunately, not all statements in referendum campaigns do. Furthermore, arguments backed by empirical data are conducive to the interactivity of a debate, because such statements can be verified and refuted by opponents. In contrast, it is difficult to argue against statements that are purely based on values, ideology or someone’s own experience – nobody can claim that the ideology or experience of the opposing side is “wrong”. Accordingly, I found in the examined campaigns that those statements that contained evidence were more responsive to the arguments of opponents.

So if the political use of evidence may enrich a referendum campaign, as my research suggests, scientists should not be afraid to see their research results being used by politicians. Rather, research or evaluation results that are relevant to ongoing policy debates should be actively presented and discussed in the public arena, and if data is not cited correctly in the media, experts on the issue can and should intervene. After all, improved knowledge of available evidence and of its relevance to the lives of citizens is crucial: it is essential for high quality referendum debates, but also for the formulation of acceptable and more effective policies.

Caroline Schlaufer is a researcher at the University of Bern. She has just finished her PhD on the use of evidence in democratic discourse. Her research interests include the use of scientific evidence in democratic processes, policy evaluation, policy narratives and the translation of policy to other contexts