Ruth Penfold-Mounce and Nathan Manning

2016 has been a significant year for voting and elections. The UK held a referendum on whether to stay in the EU or Brexit, Australian’s went to the polls in a rare double dissolution federal election, and the tumult and fanfare of the US presidential campaigns continues to roll on. However, as is the case in many established democracies there is a notable lack of trust in politicians, many people feel little connection to political parties and electoral participation is on the wane, particularly amongst young people.

With electoral politics in many democracies no longer organised by social class, politicians increasingly seek to relate to citizens in new ways. One key illustration of this is the rise in politicians performing informality, aimed at cultivating authenticity. Social media is a key platform for such informal performances, with its blurring of public and private and its typically casual and instantaneous modes of communication.

Of course, politicians are relative latecomers to social media, in which celebrities have tended to have more success. Celebrities have cornered massive followings as the public try to access the ‘back stage’ of their lives and personalities. This ‘authentic’ social media space is immensely popular and circumnavigated with skill and apparent ease by many high profile celebrities, such as Katy Perry with her 90 million followers.

Moreover, numerous politically motivated celebrities draw upon their public profile to lend an ‘authentic’ voice to a range of political causes and issues. For example, Angelina Jolie’s work as a Goodwill Ambassador for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and her ability to form relationships with politicians such as William Hague has made her a powerful political voice despite not being an actual politician.

US Presidential nominee Donald Trump is another kind of celebrity politician (see Street 2004) in that his power as a celebrity has been used to cultivate power within electoral politics. His success can be linked to his appeal as an authentic anti-politician. His informal, rude and offensive style is part of his political appeal, much like other populist politicians (e.g. Moffitt and Tormey 2014). However, the majority of politicians lack celebrity status and are overwhelmingly perceived by citizens as disingenuous, fake and self-serving.

The remainder of this article explores how young people perceive the social media use of politicians and celebrities posting about social and political issues. The discussion is based upon our recently published work ‘Politicians, Celebrities and Young People: A Case of Informalisation?’ This work draws on data gathered from young people aged 16-21 years in Australia, the UK and the US who were asked about the way politicians and celebrities use social media. Drawing on this data, we argue that politicians and celebrities have been subject to processes of informalization and that young people like politicians who present themselves as “down to earth”, “just like us”, fallible, and capable of having “fun”. Yet, at the same time, they also regarded politics somewhat traditionally, which led them to think politicians needed to retain some of the formality associated with professionalism, integrity and the exercise of authority.

Informalisation was originally developed by Cas Wouters (2007) to describe the vast social changes through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in Europe and North America which led to a general relaxation of the rules and formality of social life. These societies witnessed increased social integration and mixing as well as declining social and psychic distance between individuals and groups. In conjunction with these general trends of increased informality and egalitarianism, displays of social superiority became increasingly tabooed. As manners become less formally regulated, we are increasingly asked to look ‘natural’ and exercise greater self-regulation. So the easing of social formality does not mean ‘anything goes’, but entails a new imposition for increased self-regulation. As Wouters tells us, we are increasingly under ‘a constraint to be unconstrained, at ease, and authentic.’ (2007: 4) We think Wouters’s notion of informalisation is very useful in trying to understand the changing ways in which politicians present themselves and relate to citizens, as well as the ways other public figures engage in social and political issues. Undoubtedly other social and political changes are important in understanding the changing relationship between citizens and their representatives, but informalisation has a key role to play in an electoral politics which is increasingly mediatised and no longer organised by social class.

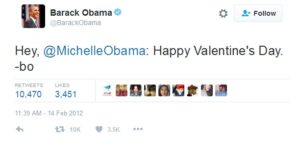

The young people from our study were generally very positive about politicians’ informal use of social media. They felt it worked to humanise politicians, revealing them as more than their professional persona, as more “real”. The tweets below from US President Barak Obama and the UK’s Boris Johnson are good examples of this.

Left-hand side: US President Barak Obama with his daughters celebrating Father’s Day, below: Obama tweeted his wife Michelle for Valentine’s Day. Right-hand side: UK politician Boris Johnson at a charity tennis match with comedian Jimmy Carr in the background.

However, there seems to be a fine line for young people regarding the informality of politicians on social media. They don’t want them to replicate the informality characteristic of celebrities on social media as they hold politicians to a different standard. Many young people in our study strongly asserted traditional expectations of politicians. They wanted them to remain professional and credible and to avoid “over sharing”. This was pronounced amongst the Australian sample particularly because of the image used in the discussion groups (see below) of Former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s ‘selfie’ after cutting himself shaving.

Nonetheless, and as seen in responses to the tweeted images below, respondents from the USA and UK were also critical of informal representations which some perceived as detracting from the professionalism and seriousness they expected from politicians or as very inauthentic.

“I think that this is nice every once and awhile, but I don’t want to see this all the time. There are better things to do than spend time posting pictures about your life when you are in charge of running the country.” (Female USA)

“ewh things like this make me cringe bet he doesnt even know who will smith is just another photo op so he can be seen as begin cool no no no.” (Female UK)

Left-hand side: Barack Obama ‘hanging out’ with Bruce Springsteen and Jay Z; Boris Johnson with Will Smith.

It would seem that informality is only acceptable and effective for certain types of well-known individuals such as celebrities, but may risk the credibility of politicians in the eyes of young people, many of whom maintain quite traditional expectations of their political leaders. As a result, young citizens seem to be demanding a contradiction: they want politicians to be “just like us”, “down to earth” fallible and capable of having “fun” but at the same time they also need to be responsible, judicious and worthy of respect. These contradictory expectations leave politicians vulnerable on at least two fronts. Firstly, if they don’t use social media or fail to share aspects of their private lives they can be interpreted as being out of touch. Secondly, if they do use social media they risk undermining their authority and respectability by being too intimate. Therefore, the informalisation process which works so effectively for celebrities has considerable limitations for politicians.

Moreover, the acceptability of informalisation for politicians is likely to be unevenly distributed across political roles, and the evaluation of such presentational styles is also likely to vary between citizen groups. Indeed, politicians’ use of social media to cultivate an authentic and accessible persona may not be a communication strategy which is available or safe for all (van Zoonen 2006). High-profile women on twitter including female politicians have endured widely reported trolling incidents including threats of rape and other abuse and the low number of women talking politics on twitter compared to men is a stark reminder of not only continuing gender inequality but also the limitations of social media as a communication strategy for some groups.

Nonetheless, based on our research informalisation should be encouraged in so far as it promotes direct, informal communication and makes politicians more relatable. The democratising potential of informalisation, celebrity culture and social media should continue to be drawn upon in an effort to create a more accessible and dialogical politics which seeks the engagement and participation of young people.

References

Moffitt, B. and Tormey, S. (2014) Rethinking Populism: Politics, Mediatisation and Political Style, Political Studies, 62: 381-397.

Street, J. (2004) Celebrity politicians: popular culture and political representation. The British journal of politics & international relations, 6(4): 435-452.

Wouters, C. (2007) Informalization: Manners & Emotions since 1890. London: Sage.

van Zoonen, L. 2006. “The Personal, the Political and the Popular a Woman’s Guide to Celebrity Politics.” European Journal of Cultural Studies, 9 (3): 287–301.

Ruth Penfold-Mounce is Lecturer in Criminology at the University of York. Her research interests encompass crime and deviance in relation to celebrity, popular culture and death. She is active in media engagement including having filmed with the Hairy Bikers for BBC 2 on the Kray Twins and recorded with Radio 4 on television violence. Nathan Manning is Lecturer in Sociology at the University of York. His research interests relate to young people’s understandings and practice of politics, as well as political dissatisfaction and the role emotions play in political (dis)engagement. He is editor of the recent volume Political (Dis)Engagement: The Changing Nature of the ‘Political’ (2015, Policy Press). The research described here was part of The Civic Network Project funded by the Spencer Foundation (Grant 201300029) and run by Brian Loader (University of York), Ariadne Vromen (University of Sydney) and Mike Xenos (University of Wisconsin-Madison).