Ingo Günther

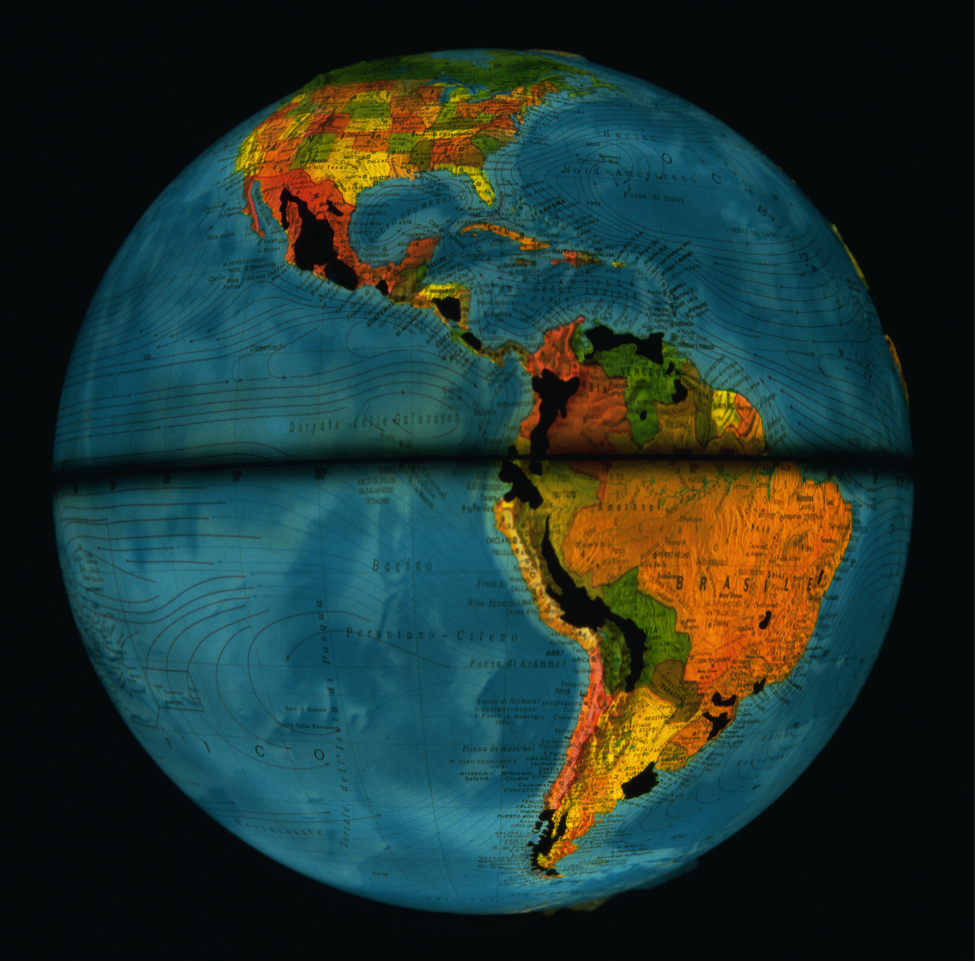

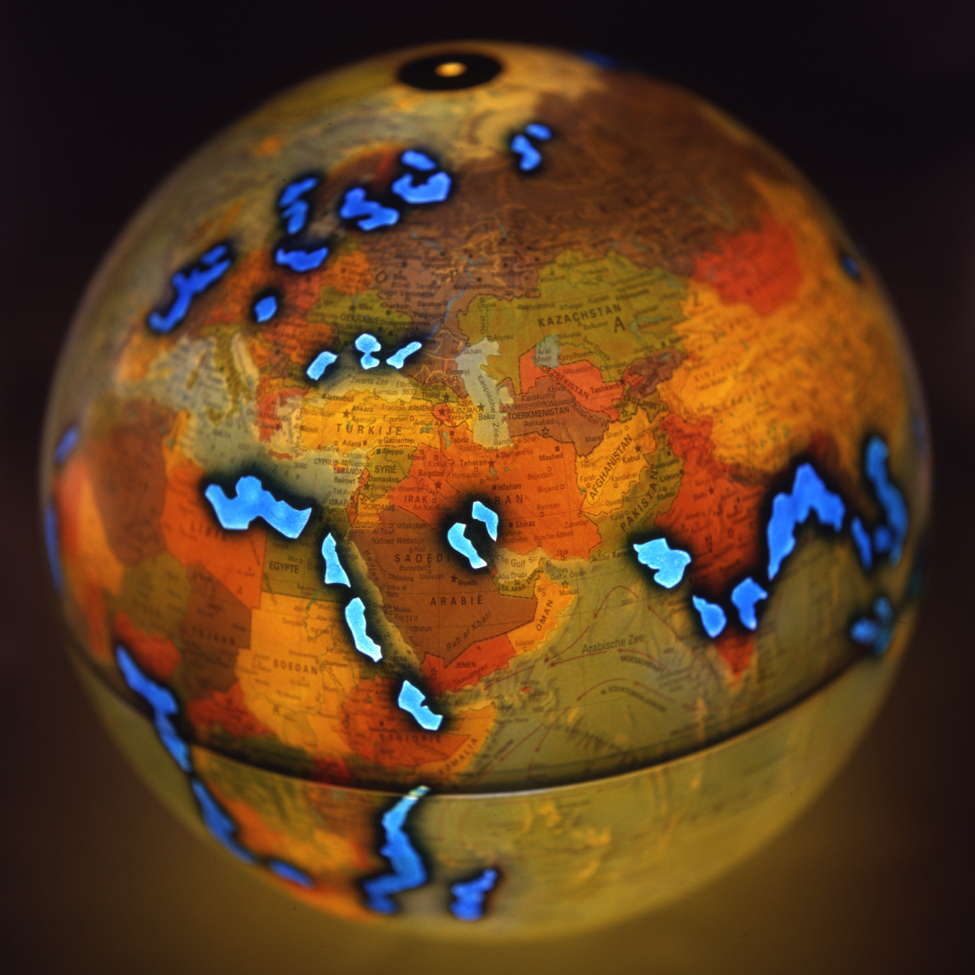

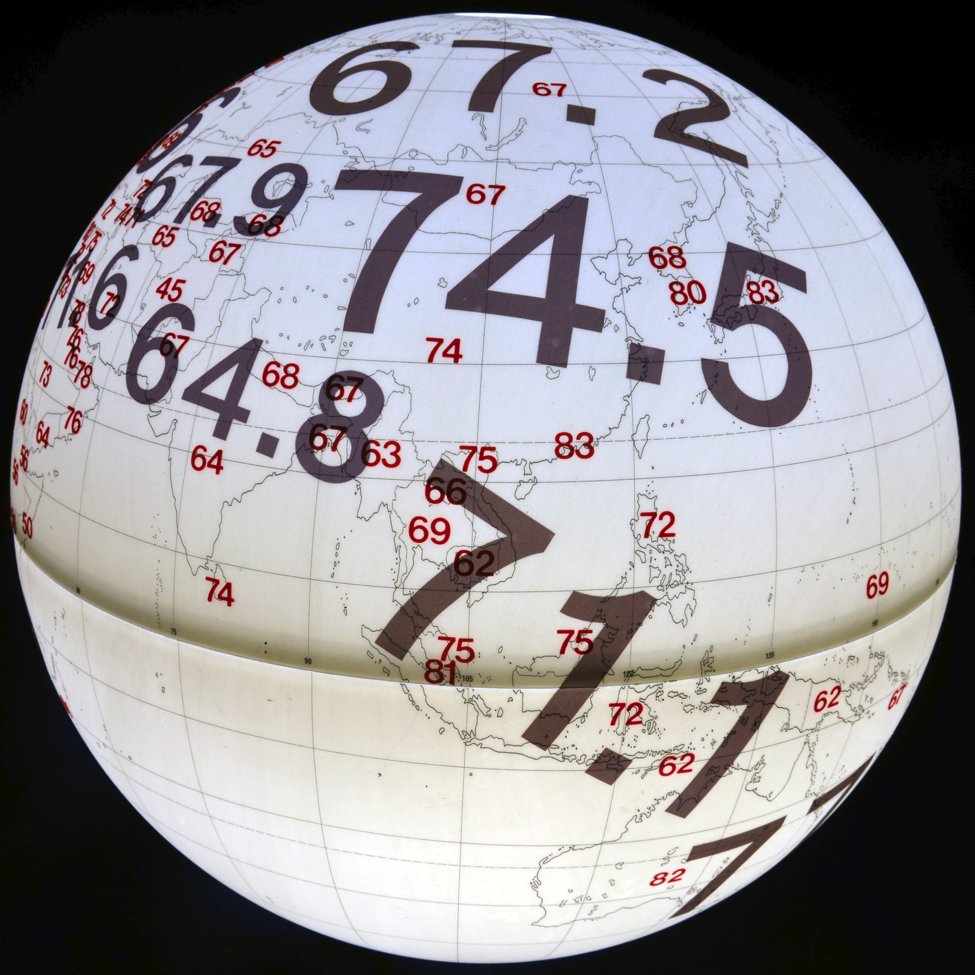

After dealing with time-critical mapping projects for reporting news in both print and television media in the mid-1980s, I ‘discovered’ the globe as a communication medium in 1988. In these pre-internet days, I saw the need for consolidating information about the entirety of the global condition and also the possibility of mapping these data on a sphere. I later came to regard this work as the quintessential medium to chronicle and represent the elements that condition the new emerging globality. It was time also to expand the 500-year-old notion of the world globe to serve the needs of the twentieth and now twenty-first century.

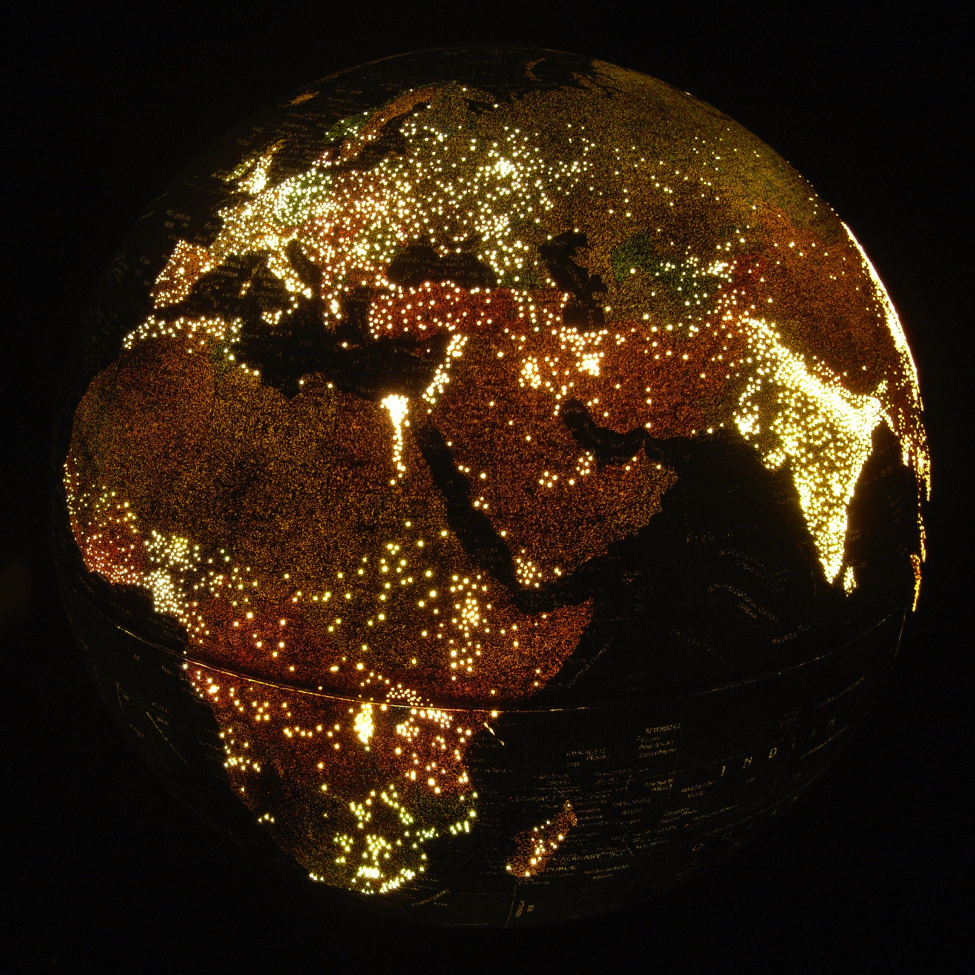

It’s been for me an enduring project that has evolved and grown steadily over two decades. In the last five years it has sprouted digital wings, allowing the results to be presented on spherical projection systems. These more recent cinematographic (moving/ dynamic) maps were made specifically for the largest high-resolution spherical movie screen on Earth: the Geo-Cosmos at the National Museum for Emerging Sciences and Innovation, Miraikan, in Tokyo. The maps are shown there on a daily basis.

What I now call the Worldprocessor project is inspired by a mix of art, journalism and scientific research. For some who have followed my work it evokes a time when art, science and philosophy occupied one field of inquiry. I have been fascinated by what came out of art and I’ve been equally in awe of human scientific achievements. While the work is essentially a form of journalism it uses both the conceptual openness of art and the constraints on inquiry imposed by science. In this context I found two books by the philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend very useful: Science as Art (note, not ‘art as science’) and his Against Method.

I am trying to be as accurate and objective as possible in this work, but equally my intention to generate intuitively accessible, comprehensive and memorable visuals. The work is specifically designed for presentation in installations so as to engage and encourage visitors to interact with the topics presented and between each other. These globes therefore serve as vectors and catalysts – or more simply as ‘conversation pieces’ – as much as they attempt to convey comprehensive data reality.

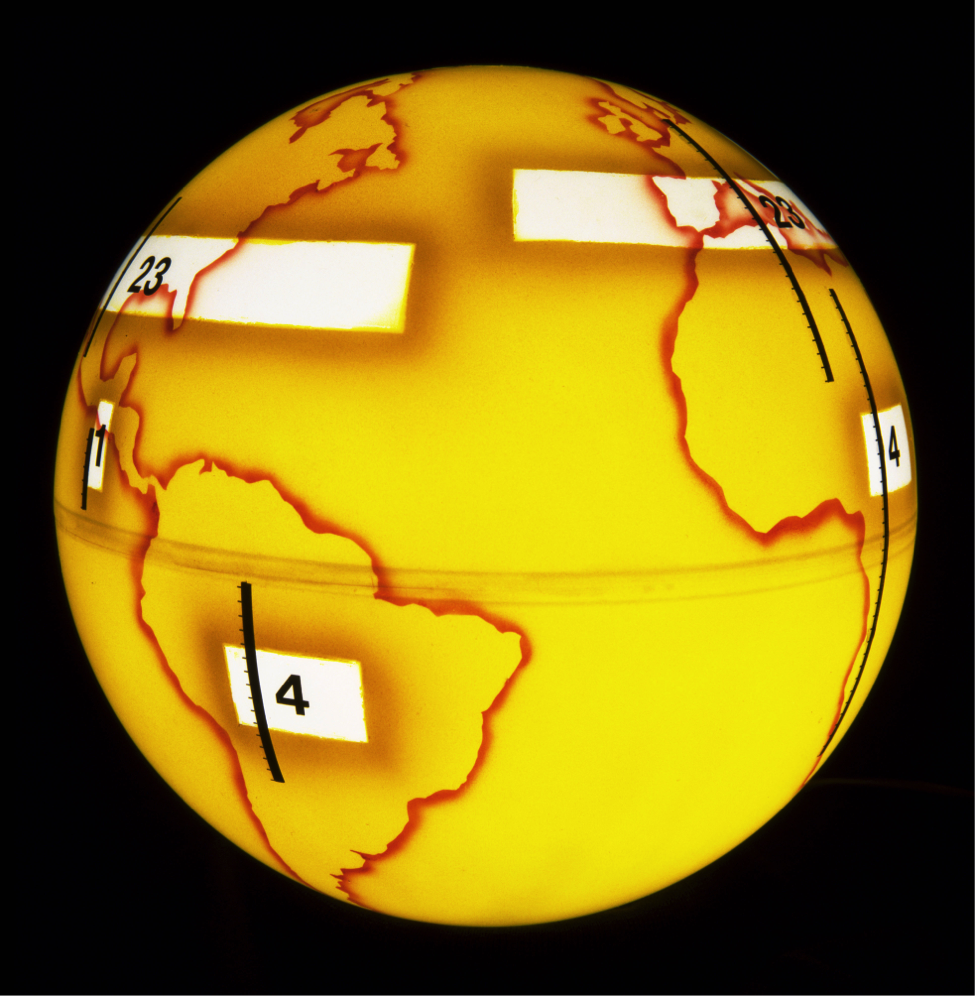

In the past, I relied exclusively on existing data to show what the world is like (beyond the geographical information provided on the globes) and to give a useful sense of proportion and dimension. But given the rapid change of data availability, I came to the conclusion that historical data, even when regularly updated, is no longer so useful. The scope and speed of change has accelerated and analog/linear projections, while remaining intuitively satisfying, are likely to mislead. Change has become exponential, especially since just about everything today is subject to datafication, connectivity, and some form of digital data quantification and control. No levelling off in this trend can be expected any time soon.

Our human culture, the modality that exists between our biological nature and the demands of our environments, is also evolving rapidly with a course set in part by technological development. Even as that has happens – by leaps and bounds – we are still in a comparatively analogue era versus the Moore’s-law-driven pace of technology. (Perhaps the recent post-human conceptual iteration allows the pace of change to be more easily understood?)

In view of these shifts in form and quickening of pace, I am now starting to expand the project into a series of data projection and forecasting globes that deal with rival and contradictory prognoses and methodologies.

In all of this work I must emphasise that I’m not interested at all it finding new ways for propagandist purposes or to rattle people and engage in agitprop. I strongly believe that people have to come to their own conclusions. As such, I offer information in the most palatable and hopefully memorable way, but I try to avoid anything that might be understood as either indoctrination or manipulation. It helps to realize that humans are a fundamentally narrative species and that facts without an narrative — true as they may be — will sink to the bottom. It is through such narratives that we form knowledge and if we are able to gather wisdom. And into that mix, we have to integrate new data.

The evolving Worldprocessor project in its many iterations has been shown in over twenty countries around the globe and has been installed permanently in Switzerland, Japan, and Germany. There is a specific web component to complement the exhibition format at www.world-processor.com

Ingo Günther grew up in Germany. He travelled to Northern Africa, North and Central America and Asia before studying Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology at Frankfurt University (1977) and sculpture and media at Kunstakademie, Düsseldorf. After blending sculptural media, journalism through TV, print and the art field he started the Worldprocessor project in 1989, subsequently become a founding professor at the Academy of Media Arts in Cologne, professor for media economics at Zurich University of the Arts and visiting professor at the Tokyo University of the Arts. As befitting the theme of this work it is shown across the globe and has won numerous prizes and awards.

Header image: Forest fires