Brigitte Nerlich

Every summer I try to read an enjoyable history of science book. This year it is Andrea Wulf’s 2015 The Invention of Nature: The adventures of Alexander von Humboldt; the lost hero of science. It reads like a fictional adventure story, a fantastic voyage, a ‘voyage extraordinaire’. When I came to Wulf’s description of Alexander von Humboldt’s voyage on the Orinoco river in Venezuela my intertextual whiskers started to twitch and I began to explore verbal and visual connections that turned out to be quite surprising… But let us first set the scene.

The book tells the story of Alexander von Humboldt’s life (travels) and work. In my distant past I had encountered the works of Alexander’s (more famous) brother Wilhelm von Humboldt (early linguist and founder of the German university system), but I never looked sideways at Alexander, his brother the explorer, natural philosopher and early ecologist. I am not alone. According to Nathaniel Rich’s review of Wulf’s book for the New York Review of Books, the “Prussian Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) is all around us. Yet he is invisible”; and this despite countless places, plants and animals having been named after this intrepid explorer.

The voyage that made Humboldt most famous (at least in the 19th century) was his exploration of South America, which included an exploration of the Orinoco. After his return to Europe, Humboldt eventually wrote his thirty-four-volume Voyage to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent, illustrated with 1,500 engravings (Wulf, p. 431). As another reviewer points out, some of his works “were technical treatises, but he also produced popular, richly illustrated books, where his passion for the natural world was combined with vivid personal narrative. These works gripped the imaginations of writers such as Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Mary Shelley and, a little later, Jules Verne.”

This brings me to the nub of my article. In the following I will explore affinities between the works of Alexander von Humboldt and Jules Verne, especially visual ones, and, after weaving together some threads that link together their factual and fictional ‘inventions of nature’, I will make some comments about the politics of nature in the Anthropocene.

Extraordinary voyages

Humboldt and his fellow scientist Aimé Bonpland at the foot of the Chimborazo volcano, painting by Friedrich Georg Weitsch (1810)

When I read Wulf’s description of the factual voyage that Humboldt and his French companion Aimé Bonpland undertook on the Orinoco, I was reminded of a fictional ‘voyage extraordinaire’ on the same river which I must have read about 30 years ago. This was Jules Verne’s novel Le Superbe Orénoque. It was published in 1898 as a part of his famous series of adventure books Voyages Extraordinaires. In this novel Verne tells “the story of young Jeanne’s journey up the Orinoco River in Venezuela with her protector, Sergeant Martial, in order to find her father, Colonel de Kermor, who disappeared some years before.” (Jeanne is one of several heroines in Verne’s novel – a topic worth exploring another time).

I was therefore not surprised to read on pp. 133-134 of Wulf’s book that “Verne mined Humboldt’s descriptions of South America for his Voyages Extraordinaires series, often quoting verbatim [from Humboldt] for his dialogues. Verne’s The Mighty Orinoco was an homage to Humboldt […] It was no surprise that Verne’s Captain Nemo in his famous Twenty thousand Leagues Under the Sea was described as owning the complete works of Humboldt.”

But there is more than just textual borrowing going on between Humboldt and Verne. There is visual borrowing too. When I saw the engraving of Humboldt’s ‘boat on the Orinoco’ in Wulf’s book (p. 65), it brought back memories of Roux’s illustrations for Le Superbe Orénoque. The boat used by Humboldt and that used by Verne’s heroes looks very much the same. I can only insert the fictional boat here – but believe me it looks like the one on p. 65 of Wulf’s book.

Such illustrations, mostly engravings, brought the world in all its exotic strangeness into the drawing rooms of the 19th-century reading population. They opened up the remotest corners of the world to inspection and enjoyment.

Making nature visible

I am not totally sure who illustrated Humboldt’s works, but I found this exhibition which lists some names, such as that of Louis Bouquet, who turns out, not surprisingly to have been an engraver (1765-1814) who illustrated, together with Wilhelm Friedrich Gmelin (1760-1820), Humboldt’s Vues des Cordillères, et monumens des peuples indigènes de l’Amérique – but more research is obviously needed here! The exhibition brochure also displays wonderful paintings by some of the artists influenced by Humboldt, who again contributed, like Humboldt’s and Verne’s illustrators to shaping how 19th -century people saw the world they could not see for themselves.

I have a bit more information about who illustrated Verne’s work. Most of the novels were originally illustrated with “woodblock engravings, chromolithographs, and chromotypographs, an early technology for color printing photographs”; some late works contain photographs. A dozen or so illustrators worked for Verne and his editor. The illustrator of The Mighty Orinoco was George Roux (1853–1929). As Wikipedia points out, “[h]e was the second-most prolific illustrator of Verne’s novels, after Léon Benett, drawing the illustrations for 22 novels in the original editions of Verne’s works with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel.”

Interestingly, some of Verne’s illustrators also worked for popular science and travel journals, such as the famous Magasin Pittoresque and Le Tour du Monde. When Humboldt died in 1859, the Magasin published his portrait. I haven’t been able to check, but there are many more images of his voyages to be discovered in such popular science and exploration magazines. Verne himself scoured popular science and travel magazines in order to find suitable images for his stories – and the more spectacular the better. Science and spectacle merged in Verne’s novels. They made nature public and, through the illustrations, visible in all its abundance, beauty and glory.

Making nature public

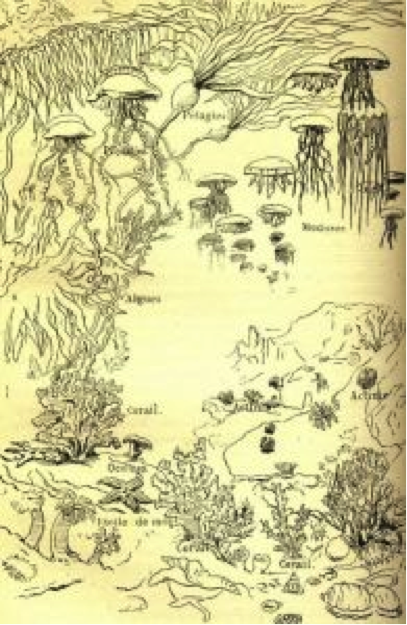

Both Humboldt and Verne made nature public through fact and fiction, through reason and emotion, through text and illustrations. Both Verne and Humboldt wrote about nature in style that tried to capture its poetic exuberance and diversity. There illustrators tried to capture this too (see here an example of an illustration for 20,000 Leagues under the Sea). “Knowledge, Humboldt believed, had to be shared, exchanged and made available to everybody.” (Wulf, p. 3)

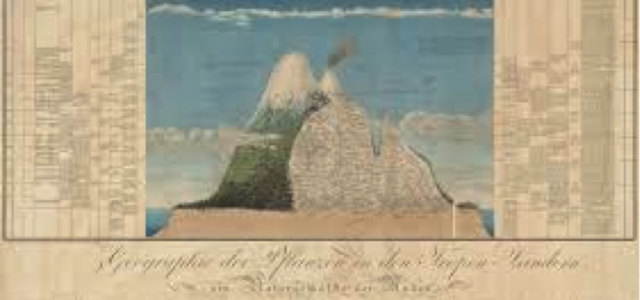

The nature that Humboldt made public was a new one. Humboldt was the first to really see nature as a network, a web, a whole made up of countless connections. This view of nature as an organic, living whole was perhaps best expressed in his famous Naturgemälde, his painting of the volcano Chimborazo (which here stands for ‘nature’ as a whole) and all the plants and animals that live on it – “he saw vegetation through the lens of climate and location: a radically new idea that still shapes our understanding of ecosystems today” (see featured image; Wulf, p. 88). This interconnected whole is a fragile one though and both Humboldt and Verne began to worry about humanity’s impact on nature.

Verne’s later novels, of which the Mighty Orinoco is one, start to engage with issues around the destruction of nature by technology. They “portray Verne’s own personal evolution—his rapidly changing views on the intrinsic value of scientific and technological growth versus that of social responsibility and ecological preservation”.

The politics of nature

Verne’s work has been said to have anticipated the ecological movement. Humboldt’s work has been called “a visual history of biodiversity” and a representation of the unity of nature, and Wulf’s book is indeed a detailed story of how Humboldt travelled the world and traced a unified image of nature. Most importantly, Humboldt is often considered to be the father of ecology. Indeed, as pointed out by Rich in his review of Wulf’s book: “In the late 1960s and 1970s, the politics of nature evolved to reflect a growing (Humboldtian) awareness of ecology.” However, Rich points out that despite this, “Humboldt makes only a passing appearance in Jedediah Purdy’s otherwise instructive After Nature: A Politics for the Anthropocene” (ibid.).

Both Humboldt and Verne, especially in his later works, began to worry about the destruction, through deforestation and over-exploitation of resources, of the very nature that they so lyrically wrote about and that was so artistically represented in the illustrations that accompanied their works. However, it is more difficult to find visual representations of these impacts on landscape and climate in their work.

Humboldt’s early insights human impacts on nature and climate left a legacy, for example in the work of George Perkins Marsh who, in 1864 wrote a book entitled Man and Nature: Or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action (a book he first wanted to call Man the Desturber of Nature’s Harmonies, but his publisher thought it would harm sales, Wulf, p. 293) Man and Nature is “one of the first works to document the effects of human action on the environment and it helped to launch the modern conservation movement.” As Wulf points out, “Man and Nature told a story of destruction and avarice, of extinction and exploitation, as well as of depleted soil and torrential flood” (p. 289)

In Verne’s work too, there is a link to what one might call the politics of nature. As pointed out by Lionel Dupuy, The Mighty Orinoco was based in part on Verne reading two books, one by Jean Chaffanjon entitled L’Orénoque et le Caura. Relation de voyages exécutés en 1886 et 1887 (1889); the other by d’Élisée Reclus entitled La Nouvelle Géographie Universelle (tome XVIII, Amérique du Sud, Les régions andines) (1893) – two works which themselves were influenced by Humboldt; and two works which contained large numbers of illustrations.

The geographer and anarchist Reclus, himself inspired by Humboldt and Marsh, and very much admired by Verne, wrote a book entitled Man and Nature: The impact of human activity on physical geography; concerning the awareness of nature in modern society. He “advocated nature conservation and […] his ideas are seen by some historians and writers as anticipating the modern social ecology and animal rights movements” (Wikipedia)….

After nature

Perhaps we need both a new Humboldt and a new Verne, a new Marsh and a new Reclus, for our era of the Anthropocene, that is to say, we need both factual and fictional accounts, verbal and visual representations, of a new politics of nature. We no longer have to ‘invent’ nature but humanity after nature.

Brigitte Nerlich is Professor of Science, Language, and Society in the Institute of Science and society based in the School of Sociology and Social Policy at the University of Nottingham. She is Director of the Making Science Public research programme, for which the author acknowledges funding from the Leverhulme Trust.

Images: Main image from Alexander von Humboldt’s Naturgemälde. Other images, Wikimedia Commons and The Illustrated Jules Verne