Gurminder K. Bhambra

On the day before the referendum on our continued membership of the European Union, I was wondering about what the result would be and how I would respond. While I hoped that Remain would win, I couldn’t say that, even at that point, it would have felt like a victory given what it had already cost us. What had been unleashed in the weeks prior to the vote was the most toxic discourse on citizenship and belonging, and the rights that pertain as a consequence. This discourse provided a context for the brutal killing of a socialist and progressive MP before the vote followed by increasing racist and xenophobic attacks on migrants and minorities after the decision for ‘Brexit’.

Alongside this politics, I also felt growing unease about the complete erasure of understanding – on the right and the left – of how Britain came to look the way it does today. Within the popular discourse of the traditional media, as well as more generally within social media, there was an almost universally accepted belief in the idea of Britain being a nation and having always been a nation. This belief in a national history, with a national population, then determined who should or should not have rights, including the rights to decent living conditions.

The right to belong and to have rights was associated with a perceived longstanding historical presence within the nation. The most visceral attacks came in relation to a sense of that national community having been betrayed by a metropolitan elite that appeared to care more for the situation of ‘non-British’ others than it did for the ‘legitimate’ citizens of Britain. ‘Put Britain first’ was the call that resounded not only from Batley and Spen but, in various degrees of intensity, from up and down and across the country. It was also mobilized in media and social scientific accounts that sought to focus attention, in particular, on the plight of a white (English) working class.

What happens when, instead of Poles, it is poor white English people herded into the polytunnels of Kent to pick strawberries for union-busting gangmasters?

Paul Mason

Racializing the working-class in the context of a populist discourse that seeks to ‘take our country back’ both plays into and reinforces problematic assumptions about who belongs, who has rights, and whose quality of life should have priority in public policy. It also works with a misguided sense of who ‘we’ are and how ‘we’ came to be. If we do not understand how we came to be politically constituted as a nation, as Britain, then our solutions to the manifest problems we are facing are likely to be profoundly misguided.

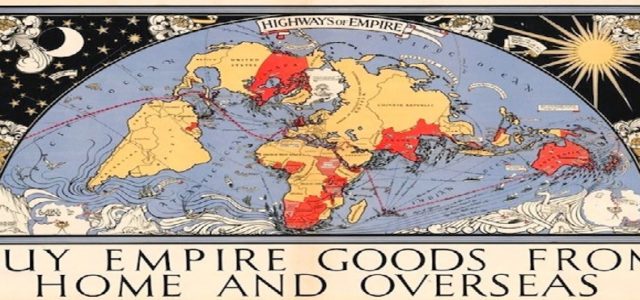

Since its very inception as a common political unit in 1707, Britain has not been an independent country, but part of broader political entities; most significantly empire, then the Commonwealth and, from 1973, the European Union. There has been no independent Britain, no ‘Island nation’.

In contrast, for most of this period, there has been a racially stratified political formation that Britain created and led to its own advantage. It is the loss of this privileged position – based on white elites and a working class offered the opportunity to see themselves as better than the darker subjects of empire (hierarchies of class and caste if you will, embodied in the hierarchies of race) – that seems to drive much of the current discourse. Austerity has simply provided the fertile ground for its re-emergence and expression.

What it is to be British cannot be understood separate from empire or the imperial modes of governance that remained dominant well into the twentieth century. While there is a much longer history that rests on the vicissitudes of empire and forms of imperial governance, here I am concerned with a shorter history: one that sets out the emergence of Britain, and what it is to be British, in the context of the decolonization of empire.

Debates on British citizenship only emerged in the metropole in the 1940s and it was not until 1981 that there was a legal statute specifying British citizenship as a category distinct from the earlier forms that had created a common citizenship status across the populations of the UK and its colonies. Disentangling a particular form of British citizenship from these earlier models was a protracted process and involved taking rights away from some citizens on the basis of race and colonial status (Karatani 2003).

In the immediate post-war period, Britain explicitly refused to consider itself as a nation and maintained empire and the Commonwealth as its key political imaginaries when thinking about what it meant to be British. This was so at least until 1973 when it entered the European Community. The idea of a special relationship with the Commonwealth also figured in arguments to leave the EU in the present, notwithstanding that the relationship had been negated in the 1970s.

Moreover, entry into the EU created a category of citizenship additional to that of national citizenship, that of ‘EU citizen’ whose rights in Britain are now being denied, as are those of British citizens in Europe; though Boris Johnson seems to believe they can be exercised by British citizens as ‘privileges’ (not rights) of remaining in a single market, while not being reciprocated for other citizens outside Britain.

In brief, up until 1948, when Britain enacted the British Nationality Act, the populations of Britain and its Dominions and colonies (both former and continuing) were understood as British subjects; after 1948, they were designated as Commonwealth citizens. People were not subjects of an authority specific to local territories, but were all subjects of British Empire or (later) citizens of the Commonwealth (whether they were in Britain or elsewhere).

At the very moment that the British government first sought to clarify what British citizenship meant, people in the colonies were formally stated to share citizenship with people in Britain and populations of the former colonies and Dominions were also regarded as citizens of the Commonwealth. This meant that they continued to have rights to travel to, and to live in, Britain by virtue of remaining within the Commonwealth.

1948 was not only the year of the British Nationality Act, but it was also the year that the Empire Windrush entered the Thames and close on 500 West Indians, holding British passports, disembarked at Tilbury Dock. This rather mundane event – of Commonwealth citizens moving within the bounds of the Commonwealth – has, subsequently, become foundational to mythologies of the changing nature (or, perhaps more accurately, face) of Britain. Mythologies that continue to reverberate in the present and have taken on a renewed political vibrancy in light of the debates regarding our continued EU membership.

While the event of Windrush is often cited as the inauguration of British multiculturalism, it should be argued, as the British government itself argued, that the British Empire and later Commonwealth was, in its very constitution, multiracial and culturally diverse. The only thing that makes the Windrush significant is the fact that it was the darker citizens of empire who were exercising their rights to move freely and legally (as many of their paler compatriots had been doing throughout history, albeit without the legal sanction of the territories they entered).

Notwithstanding the easy association of citizenship with the nation-state (and with histories of national belonging), British citizenship emerged in – and was configured by – the multiracial and ethnolinguistically plural context of empire and Commonwealth. It is this history that legitimizes the presence of Britain’s darker citizens in the UK and which gives them rights of belonging and of citizenship. Britain’s darker citizens did not come, for the most part, as migrants, they / we came as citizens.

The transformation of darker citizens from citizens to aliens over the 1960s and 1970s was based on a visceral understanding of difference predicated on race that brought into being two classes of citizenship – full citizenship and second-class citizenship. The institution of a common citizenship – Citizens of the UK and the Colonies – in the British Nationality Act of 1948 could not be undone while Britain still held formal colonies. As such, immigration into the country was increasingly managed by the passing of Acts to discriminate among citizens on the basis of race.

The transformation of darker citizens from citizens to aliens over the 1960s and 1970s was based on a visceral understanding of difference predicated on race that brought into being two classes of citizenship – full citizenship and second-class citizenship. The institution of a common citizenship – Citizens of the UK and the Colonies – in the British Nationality Act of 1948 could not be undone while Britain still held formal colonies. As such, immigration into the country was increasingly managed by the passing of Acts to discriminate among citizens on the basis of race.

While the standard accounts of citizenship align it with the contours of the nation-state, and ‘aliens’ are (or can be) admitted to citizenship; within the British context, the defining of British citizenship has been predicated on the basis of making citizens into immigrants on the basis of an explicit racial hierarchy. Indeed, as Hampshire has comprehensively demonstrated, ‘the development of immigration controls in post-war Britain was governed by a racial demographic logic’ (2005: 77).

This points to the current British polity as deeply structured by race such that the state itself – and all associated concepts, such as citizenship – are themselves racialized. The issue of race is not simply about those who look different being present within British society; but about how the state is itself constructed on a racial ideology. It is this that social scientists and policy analysts seem not to take on board when making arguments only about, or prioritizing, the white working class.

Yes, the immigrants got the blame from the Brexiteers – but that’s perhaps because the Labour party and Conservative party alike have chosen to put class to one side in politics and concentrate instead on matters of identity, so long as that identity isn’t one of Englishness, which is what, oddly enough, most English people consider to be important.

Tim Lott

On the political right and the left, white commentators use ‘British’ or ‘English’ or ‘the working class’ always to mean ‘white British’, ‘white English’ and the ‘white working class’. They don’t even need to think of having to qualify what it is to be British; it is such the common-sense position that to be British or English is to be white. Those who argue for a class analysis on this basis are, in fact, offering the most racialized of identity politics, albeit one that is unconscious to itself.

The mobilization of ‘Churchillian’ values and freedoms by Boris Johnson and the use of the iconography of spitfires by Nigel Farage’s UKIP, aligns with the discourse of the far-right across the EU that sees Europe itself as white and under threat from the darker subjects it had previously subjugated. This mythology of a white Europe or a historically white Britain seriously misrepresents the multiracial political formations that were the context for the emergence and development of many European countries, including Britain, as they are today.

No subject of empire asked for that subjugation. Having been included through subjugation, it seems perverse to now be excluded by those, careless in their history and wanton in their analysis, who articulate a conception of the body politic and the body social as white, and do not wish inclusion on terms of equality.

We didn’t wish inclusion through subjugation, but we will not be wished away. If we want a future that addresses the injustices that blight our contemporary times, we must rethink our analyses to take into account the imperial configuration of Britain and all those who were subjects within it and subject to it. If this is not done, then that demonstrates a commitment to a racialized national history that has no space for its darker subjects. This is choice that clearly illuminates on which side of the line we stand as we move from the 2000s to the 1970s to the 1930s.

References and Further Reading

Hampshire, James 2005. Citizenship and Belonging: Immigration and the Politics of Demographic Governance in Postwar Britain. Palgrave: Basingstoke.

Hansen, Randall 2000. Citizenship and Immigration in Post-war Britain: The Institutional Origins of a Multicultural Nation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Holmwood, John 2000. ‘Europe and the “Americanization” of British Social Policy,’ European Societies 2 (4), 453-82.

Karatani, Rieko 2003. Defining British Citizenship: Empire, Commonwealth and Modern Britain. Frank Cass: London.

Gurminder K Bhambra is Professor of Sociology at the University of Warwick and Guest Professor of Sociology and History at Linnaeus University, Sweden. She is author of Connected Sociologies and Rethinking Modernity. She tweets in a personal capacity @gkbhambra