William Outhwaite

This is not the title I expected to use. I was hoping to begin by saying it was all just a dream. There was indeed, and remains, no realistic, or at least attractive, future for the UK or any of its component parts outside the EU, as documented at length in analyses by almost every expert source. But the dream came true, as when you dream your house is flooded and wake up to find that it actually is.

What we have experienced in the UK is the conjunction of three phenomena: a world problem, a European or EU problem and a British (or, more properly, English and Welsh) problem. The world problem, well-illustrated at the same time by the spectacular performance of two outsider candidates in the US presidential election campaign (one of them still in the running), is a widespread disaffection with established political parties, political leaders and political systems as a whole and the rise of (mainly right-wing) populist politics. The sociolinguist Ruth Wodak wrote that in 2000, when the Austrian far-right FPÖ entered a coalition government, ‘probably very few scholars could have imagined that in 2014, such parties would be able to win the elections for European Parliament in France or the UK…’ (1).

The European problem is one of disaffection with the politics of the European Union and to some extent with the EU as a whole. This is most extreme in the UK, which now follows Greenland into withdrawal, but can be found to varying degrees across the Union. The same goes for the populist politics mobilised against it. Boris Johnson’s comparison of the EU’s integration strategy with those of Napoleon and Hitler was prefigured in 2014 by an Austrian MEP who called it a dictatorship, compared to which the ‘Third Reich was probably informal and liberal’ and that it was also a ‘conglomerate of negroes’ (Wodak, page 63-4). He later apologised, unlike Johnson, who merely complained about the way the campaign had been dominated by sound-bites and twitter storms. By precipitating British exit through a gratuitous referendum called to ‘shoot the UKIP fox’, the British Conservative Party has given the lead to ‘insurgent’ movements across Europe that are almost all hostile to what are ostensibly its (and the EU’s) foreign policy and human rights objectives.

The British/English problem (2), is a widespread unwillingness to see EU membership as a fact of life and a permanent ambivalence about the UK’s membership, culminating in an even balance of opinion in the referendum campaign and a narrow majority for the leave option. It can be seen in a broader context as the failure of the EU to attract three western European states and, so far at least, to reach a stable accommodation with others further east. Two of the westerners, Norway and Switzerland, remain outside the EU, but either a member of, or closely associated with, the European Economic Area and with both of them members of the Schengen area. It remains to be seen whether the EEA road, however unsatisfactory it has proved in both countries, will be taken by the UK, where anti-EU voters were misled to expect a fall in EU immigration. The latter could indeed be achieved, but not within the EEA, though the economic collapse which is likely to result from Brexit would reduce the appeal of England as a destination, and this may enable some sort of fudge which keeps the UK at least in the EEA. The Canadian/Singapore/Hong Kong alternative suggestions are really for the fairies, as the WTO chairman made clear some weeks ago.

The implications for the UK are radically open between a range of bad outcomes. For the EU, it sharpens up the issue of the Union’s variable geometry or differentiated integration model. This is particularly important in relation to the euro, in terms of both widening (its prospective extension to all EU member states except Denmark, whose currency is pegged to the euro and likely to remain so) and deepening (the closer integration of the Eurozone which all observers agree is required).

There was considerable debate in the long months preceding the UK referendum about a possible domino effect of Brexit, though less about a similar domino effect or, better, Pandora’s box from Bremain. In either event, and we now know which is the reality, other member states might demand the same sort of special treatment afforded to the UK, with the threat of a popular referendum in the background. The failure of these (admittedly trivial) ‘concessions’ to persuade the UK to remain has done little to change this. Nothing is easier than for member states to defer indefinitely their adoption of the euro, even if they are officially committed to it. Any plans for more intrusive surveillance and supervision within the Eurozone could be expected to reinforce this unwillingness to participate. The Schengen area is in some disarray, and another obvious area for opting out.

As far as the UK is concerned, the historian Brendan Simms has offered a striking projection which combines federalism within the Eurozone and a formal confederation with the UK and other states which wished to remain outside it, in something like the present European Economic Area. The confederation would supervise the Single Market and also, for example, the City of London, but would give Britain ‘a much bigger role than Norway or Switzerland, and indeed than she has today…’ He notes, on the same page, that this was envisaged by Jacques Delors in 2012: ‘If the British cannot support the trend towards more integration in Europe…I could imagine a form such as a European economic area or a free-trade agreement’ (3).

Simms takes much more seriously than I would do the British sense of its special position as an established and, in the mid-twentieth century, undefeated democracy: ‘Europe was designed to fix something that was never broken in Britain’ (page: 237). Switzerland can perhaps more plausibly portray itself as a special case, since until 2002 it also declined to join the UN, despite providing its main European base in Geneva. The UK’s sense of itself as distinct from the European continent is largely imaginary and grounded in a reading of history which stresses its maritime character and glosses over its permanent imbrication with the rest of Europe. (Ireland is two seas away from the mainland, not one, but has much less of a sense that this makes it somehow less European.) But as with the German Sonderweg, if you think you have a special path, you do.

How all this will pan out remains to be seen. It is hard to envisage much willingness in the rest of the EU to concoct a special position for a state which voted to leave it. What the UK has done is to place exit as an agenda item for the whole of the Union. This can be found here and there in the rhetoric of some populist parties, but the UK’s departure, however disastrous it turns out to be, does at least show that it is possible. This cuts more ice, as it were, than the departure of Greenland in 1985. Just as the Scottish referendum in 2014 made it harder for Madrid to resist one in Catalonia, it is now hard to see how any member state could resist one if there were a significant demand for it, as some recent polls have suggested.

In the UK itself, there will be a great deal of discussion comparing the two recent referendums, separated by less than two years. There was a morphological similarity, with the expectation that Scotland would vote no to independence followed by a last-minute panic that it would vote yes which brought together the three main UK parties. In Scotland, however, this may have helped to secure a no vote, though it further damaged the image of the Scottish Labour Party. In the UK referendum, it may even have had the opposite effect, with the consensus of most of the political class (though not the ruling Conservative Party) as well as virtually all independent expert organisations serving only to strengthen the sense that Brexit was a heroic, if slightly risky, option. ‘Very well then, alone’, in the words of the famous cartoon by David Low as the rest of Europe capitulated to the Nazi invasion and the US stood aside.

The Scottish debate was however remarkably civilised compared to that later in the UK. Some ‘no’ supporters were accused of being unpatriotic, but there was little to compare with the temperature of the media debate in the UK less than twenty months later. The killing of a Labour MP and ‘remain’ supporter by a self-identified right-wing fanatic (‘my name: death to traitors, freedom for Britain‘) just over a week before the vote was the climax to months of mutual vilification by the two sides.

Media bias was also important. Unlike the situation in the Scottish referendum, the UK press massively supported Brexit. The UK, along with Austria has long stood out for its eurosceptical press coverage, just as the UK and Latvia stood out in 2015 for their level of ignorance.

The BBC felt itself obliged to take a neutral position between the two camps. In what became a standard pattern, expert analyses were ‘balanced’ by a perfunctory rebuttal, often based on ‘facts’ which had long been shown to be false or misleading. Michael Dougan, an expert on EU law, aptly compared the so-called debate to one between evolutionary biologists and creationists.

When President Obama was criticised for predicting that a post-Brexit UK (or whatever remained of it) would be at the back of the queue for alternative trade deals with the US he rather plaintively suggested that, since there had been so much discussion of the issue, he had thought that people might be interested to have the opinion of the US President.

Separatist nationalism, to which the Brexit campaign can in some ways be assimilated, divides according to whether independence is valued whatever the cost or, alternatively, is seen as in any case the least costly option. Richer sub-states, like Slovenia in Yugoslavia and Catalonia in Spain, have typically stressed the benefits of getting out from under an economically weaker union. This was contentious in the Scottish case, and the current lower oil price, as well as the depletion of the remaining fields, has made the issue more problematic. In the Brexit referendum, the EU was variously portrayed as threatening and as itself threatened by economic decline and political collapse. In a milder version of the second position, membership was seen as something possibly beneficial in the past but which the UK, its economic fortunes revived by Thatcherism, no longer needed or benefited from. This was typically conjoined with the better grounded argument that the character of what is now the EU had changed since the 1975 referendum, or, at least, since the Maastricht Treaty of 1992.

In the UK, however, the separatist vote was largely indifferent to the almost unanimous warnings of economic disaster which, as I write this on the day after the vote, are already being borne out. Scotland, I expect, will choose independence within the EU. For Northern Ireland, the issue of reunification is back on the agenda, with the likelihood of a revival of the terrorism which had largely fizzled out by 2016. England, likely to be dominated by right-wing governments hostile to state aid, will presumably leave Wales to rot. However badly the result turns out for England and Wales, voters elsewhere in the EU may choose to follow suit. The UK, which had a great deal to offer the EU and Europe as a whole, and in the recent past substantially reshaped the EU according to its neoliberal priorities, has now little to offer to either except disruption and dissension. At worst, it could cause the EU to develop into the shape favoured by the extreme right and its supporters in Russia, which might politely be called Gaullist: a loose association of (so-called) sovereign states.

How did it come to this? We might separate the short-term explanations from longer-term considerations. The referendum was designed to fix a problem of David Cameron’s position in the Conservative Party and the challenge to that party from UKIP. One of the first responses to the result in the early hours of June 24th, was from a Conservative MP welcoming the prospect of cutting into UKIP support. Cameron is now dead in the water, his party likely to split and the UK presumably doomed as a unified state. Rainstorms in London may have depressed the turnout and hence the remain vote (I rather shocked a fellow passenger as we disembarked at Heathrow by saying that I hoped that better weather might determine the outcome, but this is the way things go). As usual with EU referendums, voting had rather little to do with the question at issue. Much of the support for leave was driven by the effects of austerity policies, combined with the run-down of public housing and health services. There was something of a revival of that classic sociological topic, class politics, though in a form which supports the right rather than the left. The demise of Labour in Scotland is likely to prefigure a similar decline in England.

The longer-term explanation takes us back to the UK’s initial unwillingness to join what has become the EU, its immediate referendum in 1975, and its ongoing hesitation about its membership. De Gaulle, when he announced his veto in 1963, suggested that it was not a viable prospect. There are three possible answers. One is that the UK should indeed never have been allowed to join, another that membership was useful for the UK (and perhaps also for the Union) for a time, but now no longer, and the third, that a tense but effective partnership was wrecked by an idiotic decision to put membership once again to a vote, in a political culture hopelessly corrupted by an anti-EU press and by politicians happy to blame Europe. The last of these is my view. In the UK’s essentially two-party system, the Conservatives since the late 1980s have nurtured an increasingly anti-EU position earlier represented by Labour, returning it from a fringe obsession to the political mainstream. Sociologists are used to choosing between state-centred and society-centred explanations. Here, I think, the answer is clear: the UK is socially very like the rest of north-western Europe but happened to diverge politically, building on earlier differences and drifting further away from it.

Jürgen Habermas entitled one of his innumerable articles ‘learning from catastrophes’ (and did his best to argue against this one). For the EU, it can hardly be business as usual. To lose one member state (or two if one counts Greenland) might seem like an accident: to lose more would be carelessness. One lesson from the UK is that where electorates are excited by the prospect of an in-out referendum there is little to be gained by negotiated ‘concessions’ or the presentation of expert evidence. A more democratic Union, of the kind I have argued for in Discover Society (and elsewhere), might, I have to admit, be even more prone to populist subversion. The likely break-up of the UK will not frighten voters in Catalonia, the Basque Country, Brittany or Belgium – or even northern Italy. Its economic decline, unless it happens even faster than I expect, will not be soon enough to discourage separatist moves in other member states.

Clutching at straws which might alleviate the gloomy tone of this assessment, I should point out one for the UK and one for the EU. The UK’s exit will be a little easier than it would be for states in the Eurozone. For the EU, the loss of a member state which had been a drag on its already snail-like integration process may free things up, or at least add a sense of urgency to reforms of whatever kind, whether towards closer union or a more variable geometry. On the other hand, having to waste yet more effort on negotiations with the UK will inevitably distract attention from more important matters, just as making special arrangements with Switzerland has taken up a remarkable amount of time which could have been better spent. The EU resisted the temptation to tell Cameron to stuff his negotiating demands, but although there is now nothing to be done but damage limitation this can only be more disruptive, and whatever goodwill remained is now gone for ever.

When people said over the past years that they could not imagine the UK leaving, I reminded them of the Czecho-Slovak divorce in 1992 and the danger of drifting into an outcome which hardly anyone wanted, except for some opportunistic politicians. But whereas there it took two to tango, in this case it is just the British who have danced away to disaster.

Notes:

(1) Wodak, Ruth (2015) The Politics of Fear. What Right-Wing Populist Discourse Means. (London: Sage), page 181.

(2) Like England, Wales was evenly split. Scotland was quite solidly for remain. In Northern Ireland, a late shift of opinion, as measured by a poll a week before the vote, raised leave from less than a quarter to nearly a third, with Catholics solidly for remain and Protestants shifting towards leave. In the final result, however, there was a substantial majority for the remain option, though the politicians support leave. Not surprisingly, Martin McGuiness has called for an all-Ireland vote on reunification.

(3) Simms, Brendan (2016) Britain’s Europe. A Thousand Years of Conflict and Cooperation. (Harmondsworth: Allen Lane), page 239.

William Outhwaite is emeritus professor of sociology. He taught European studies and the sociology of contemporary Europe at the University of Sussex (in the School of European Studies) and Newcastle University (in the School of Geography, Politics and Sociology). He is the author of European Society (Polity 2008), Critical Theory and Contemporary Europe (Continuum 2012), Europe Since 1989 (Routledge 2016) and Contemporary Europe (Routledge, forthcoming).

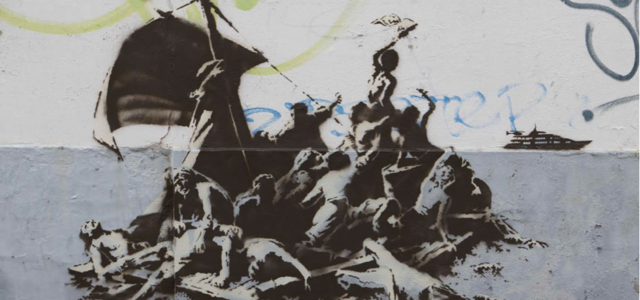

Image: Banksy, ‘Raft of the Medusa’ at the Calais Jungle Refugee Camp, December 2015