Goldie Osuri

Recently, I wrote an expert report for a legal case for political asylum in the UK regarding an upper-caste Hindu Indian convert to Islam on the basis of the protection of religious freedom. In learning the details of the case, I also learnt something about the current everyday public assertions of majoritarian/fascist nationalism in India. Upon hearing about the young man’s conversion to Islam, his fairly rich father hailing from a village in Haryana disowned him, publicly; this was printed in the English and Hindi local newspapers. The young man feared going back to his family as he thought he might be made an example of through honour killing.

His father was a former head of the local panchayat and held strong Hindutva views. Given recent lynchings of Muslims, violence against Christians, and campaigns for ghar wapsi or reconversion to a Hindutva version of Hinduism, these were valid fears regarding the extent to which Indian politics appear hostage to an ‘authoritarian’ or fascist populism. The lawyer’s comment to me – that such an application was perhaps unlikely to be successful as India’s Muslims number at about 14.2% of the population—illustrates the ways in which the relationship between state sovereignty, majoritarian nationalism, and the minoritisation of communities produces fraught, unsettled, and precarious lives.

Since the 1990s, there have been ongoing debates regarding secularism and religious nationalism in India. The crisis of secularism was announced when the BJP won electoral success. Neo-Gandhians like Ashis Nandy proclaimed the failure of Nehruvian state secularism, dominant since Independence, decrying it as a colonial western elite import and advocated a communitarian notion of tolerance based on the resources of everyday life. In contrast, Rajeev Bhargava (2010), a staunch advocate of Nehruvian secularism, has argued that the model of Indian secularism is the best solution in that it provides protection for minority rights. Secular nationalism in India, in many of the scholarly debates, has been seen as a thorny issue, but a necessary counter to the threat of religious nationalism. Religious nationalism is now no longer a threat; it is an inextricable part of the Indian political landscape. The current Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, is a member of the RSS—the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh—a right wing fascist organization inspired by the masculinism of European fascism.

The apparatus of nation-state sovereignty (territory, laws, and jurisdiction) in South Asia, inherited through the infrastructure of colonial sovereignty, is characterized by another inheritance, that of anti-colonial upper-caste norms of the nation as Hindu. Precisely because South Asian nationalisms have been ethnicised through religious identity and linked to an understanding of religious difference as a threat regarding divisible sovereignty, religious difference and its regulation becomes a preoccupation of both secular states as well as theological ones. Indeed, Aamer Mufti suggests that what theorists of nationalism in the Indian context have failed to recognize is that rather than ‘a great settling of peoples’ the ‘distinguishing mark’ of secular nationalism is that ‘it makes large numbers of people eminently unsettled’ (2007: 13). So, The creation of a ‘minority’ status for Muslims, Christians or Sikhs in India is one such unsettling effect. In times of crisis, a majoritarian nationalism can manifest itself as the violence of authoritarian populism through both state and non-state groups directed against minoritised communities. In recent years, this violence has been mainstreamed by Hindutva nationalism.

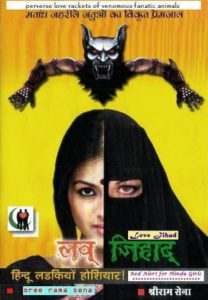

In Religious Freedom in India: Sovereignty and (Anti) Conversion (2013), I explored the relationship between sovereignty, nationalism, minoritisation and the regulation of conversion. Anti-conversion campaigns are part of a cluster of other related campaigns – which might be thought of as led by authoritarian populism: ghar wapsi or reconversion to an imagined Hindutva fold, cow protection, and love jihad (the idea that Muslims seduce Hindu women into marriage in order to convert them). These are anti-Muslim and anti- Christian, but they are also casteist and communalist; i.e., they are not only about religious difference, but also about miscegenation between castes.

Stories of violence against Dalits, Muslims and Christians proliferate. Examples include the premeditated lynching of Mohamad Akhlaq in Dadri, Uttar Pradesh in 2015 to the lynching of cattle traders Muhammad Mazloom and Azad Khan in March 2016 (linked to the beef ban and cow protection campaigns). In July 2015, a Dalit engineering student, V Gokulraj was murdered for a perceived love affair with a Brahmin woman in Tamil Nadu. In April 2016, a Christian pastor and his wife were doused with petrol during an attack on a church in Chattisgarh. Violence against Christians continues intermittently. In Karnataka, a consensual (even by their parents) Hindu-Muslim marriage was protested as if it were a conspiratorial ‘love jihad’ by Hindutva and caste activists. Fortunately, the marriage went ahead—perhaps because it was championed by the parents.

My critique of secular state minoritisation and the claims of religious nationalism takes a different route to that of both secularists as well as neo-Gandhians. If we study conversion or anti-conversion laws and campaigns as one key site to understand the normative secular idea of India as a Hindu majority nation or expression of Hindutva nationalism, then the link between the concern for secular state sovereignty and upper-caste religious nationalism becomes apparent. It is important to note that European structures of sovereignty and the experience of colonization in South Asia enabled or facilitated the entry of secular majoritarian nationalisms. In a time when Hindutva nationalists govern, religious difference becomes a way to assert these majoritarian nationalisms by pushing for national anti-conversion laws, cow protection campaigns (including beef bans campaigns and laws), and love jihad campaigns. In this sense, perhaps what we are witnessing is an expansion of religio-national sovereignty over the practices of everyday life—eating practices, the regulation of love, marriage, sexuality and so on.

Currently, we live in a time where the gloves are off, and either violence or incitement to violence seems to be order of the day. Can we simply formulate a critical secularism and leave it at that? One strategy to address this era is to think through the relationship between sovereignty and nationalism. What are the terrible costs of the nation-state sovereignty’s obsession with minoritised demography in relation to national integrity? The techniques of sovereign power, whether they are exercised by the secular state or the theocratic state, whether they are exercised by non-state actors (local sovereigns or bade aadmi as Thomas Blom Hansen might call them), are engaged in the necropolitics of disintegration — of otherised ‘anti-national’ bodies and occupied bodies. I mention occupied bodies as in the case of Indian nationalism and its practice of sovereignty, there are its occupations at stake. Here the question is not one of minoritisation, but a struggle for freedom in Kashmir and the Northeast. Mohamad Junaid (2013) outlines the texture of Indian occupation in Kashmir and the Kashmiri struggle for azadi (freedom), and illustrates the terrible costs of Indian sovereignty there. From this perspective, the story of a popular Indian anti-colonial independence struggle and the legitimacy for Indian sovereignty cannot be sustained. For many Kashmiris, the accession of Kashmir to India is itself a questionable point, one that is mourned rather than celebrated.

Given these dual challenges to Indian nationalism, perhaps the time has come to ask along with K.N. Panikkar (who cites Rabindranath Tagore) whether it is nationalism itself that is a menace. And furthermore, we might ask with Kamala Visweswaran (2013), what forms of sovereignty are intelligible outside the nation-state form? Is it possible to envision sovereignty itself otherwise—as one that is an embodied practice of genuine co-existence rather than a concern for territory? This story is of course much more complicated in the context of capitalist and neoliberal imperatives. From a minoritised or occupied position, however, to affirm the current status quo of majoritarian/fascist nationalisms in South Asia and elsewhere appears more dangerous. Indeed to affirm the status quo of majoritarian nation-state sovereignty it is to leave the self open to sovereignty’s technologies of bodily disintegration.

References

Bhargava, Rajeev 2010, The Promise of India’s Secular Democracy, New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Hansen, Thomas Blom 2005, ‘Sovereigns beyond the State: On Legality and Authority in Urban India’, in T.B. Hansen and F. Stepputat (eds.) Sovereign Bodies: Citizens, Migrants and States in the Postcolonial World, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Junaid, Mohamed 2013, ‘Death and Life Under Occupation: Space, Violence, and Memory in Kashmir’ in K. Visweswaran (ed) Everyday Occupations: Experiencing Militarism in South Asia and the Middle East, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 158-190.

Mufti, Aamer 2007, Enlightenment in the Colony: The Jewish Question and the Crisis of Postcolonial Culture, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Nandy, Ashis 1998, ‘The Twilight of Certitudes: Secularism, Hindu Nationalism and other Masks of Deculturation’, Postcolonial Studies 1 (3): 283-298.

Osuri, Goldie 2013, Religious Freedom in India: Sovereignty and (Anti) Conversion, London: Routledge.

Visweswaran, Kamala 2013, (ed) ‘Introduction’ Everyday Occupations: Experiencing Militarism in South Asia and the Middle East, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 1-28.

Goldie Osuri is Associate Professor at the Department of Sociology at the University of Warwick. Her monograph, Religious Freedom in India: Sovereignty and (Anti) Conversion (Routledge, 2013) and other recent publications focus on sovereignty struggles in the context of nationalism, transnationalism, and colonialism through critical, post-structural approaches.

Image Credit: Indian Army Occupation in Srinagar, Goldie Osuri