Les Back

Our commitment to social criticism means that the tone of sociological writing is often in a despairing or hopeless key. Ken Plummer commented, in an interview with the British Sociological Association’s magazine Network, that sociology should not: “Just be a counsel of despair. We need a sociology of joy, a sociology of human flourishing, a sociology of hope.” However, twentieth century intellectuals had very contrasting views of hope and its political connotations.

To live in hope, for Albert Camus, is to surrender to inertia, fatalism and defeat. He pointed out that, for the Greeks, hope is the last, and most dreadful, of the ills left inside Pandora’s box. Camus concluded: “I know no more stirring symbol; for, contrary to the general belief, hope equals resignation. And to live is not to resign oneself” (2005: 14). Others, such as, Raymond Williams argued that hope can be found in the infinite resilience of people to endure damaged life: “That is why I say we must speak of hope, as long as it doesn’t mean suppressing the nature of the danger” (1989: 322). As John Berger argues we have to take the world in before we can hope to change it.

Michael Taussig warns that for social critics – including sociologists – there is a peculiar kind of consolation in adopting a hopeless position. Here the “temptation to link lack of hope with being profound.” A curious comfort can reside in the critical certainty of a last instance pessimism. In a way, this blind pessimism is the reverse of the, often repeated, adage about sightless optimism. Pessimists are never surprised because they can be confident that things will inevitably turn our badly.

Far from being a universal human attribute hope is situated in time and in particular kinds of contexts. Is hope a system of belief? “Hope is a rope…” writes Henri Desroche in his study The Sociology of Hope translated from the French in 1979. Hope is like the Fakir’s rope, the shaman throws the rope into the air and it holds. “And when humans grab hold of it and pull themselves up, it takes the strain… For if hope is identified with this constitutive imagination, it cannot be so without sharing in both the characteristic fullness and emptiness of the imaginary.” I want to come back to this approach to hope because it always makes hope a property of the future and also a kind of phenomenology. However, I want to argue in contrast that the sociology of hope needs to be tuned to the conditions of the present.

Hope involves an attention to daydreaming in the possible and the not-yet decided conclusion. This is at the heart of Ernst Bloch’s The Principle of Hope written in the dark times of Nazism. Bloch’s principle of hope is cast in contrast to fascism and its fear principle. He wrote: “It is a question of learning hope. Its work does not renounce, it is in love with success rather than failure… The emotion of hope goes out of itself, makes people broad instead of confining them… The work of this emotion requires people who throw themselves actively into what is becoming, to which they themselves belong.”

Jonathan Lear’s philosophical anthropology Radical Hope offers one such case. Plenty Coup – last chief of the Crow Nation – faced with cultural devastation – when the basis for a way of life is destroyed and made untenable. He uses Plenty Coup as an exemplar of a kind of radical hope. Faced with this desperate situation he does not revert to a messianic vision and Sitting Bulls’ Sioux ghost dance. Rather, Plenty Coup takes his bearing from an attention to present circumstances.

In a dream Plenty Coup sees the vision of the Chickadee – an emblem of Crow culture. The vision told him to wait and to watch and listen. The Crow could not halt the devastation but they were able to act in new ways, sustaining vestiges of the past and avoiding utter annihilation. The ‘white man’ broke promises and encroached on their lands but nonetheless, Lear argues, Plenty Coup’s radical hope was vindicated and the Crow survived.

Radical hope is made and shaped in the here-and-now by the chickadee bird listener who takes in what is happening and interprets its meaning. In this sense hope is not a faith that delivers a future. Rather, it is an attention to the present and the expectation that something will happen that will be unexpected and this will gift an unforeseen opportunity.

Hope can also be the enemy of other kinds of certainty – its emergence is too provisional and leaves too much to chance. In Studs Terkel’s book Hope Dies Last he writes of interviews with some military people including the pilot who dropped the bomb on Hiroshima. Admiral Gene LaRoque articulates a hostility to hope precisely because it undermines military logic: “Never once do military people think about hope. Hope in my view is a wasted emotion. People hope to win the lottery when they buy a ticket. They hope to win it because there is no chance. If we want a better world, we as human beings ought to do what we can to bring about the change. Hoping is a futile mental exercise.” For the military mind the unfinished and undecided is the enemy of conviction.

The expectation that hope licenses is empty. This is precisely what Lauren Berlant calls a cruel optimism. This kind of optimism manifests as a cluster of promises, which are “attached to compromised conditions of possibility.” The result is an attachment to a problematic object that is unable to deliver on its promise. Famously Antonio Gramsci described his view on the subject in a letter dated 19th December 1929. He described it as one that “never despairs and never falls into those vulgar, banal moods, pessimism and optimism: my mind is pessimistic, but my will is optimistic.” In fact, the phrase so often attributed to Gramsci is a borrowed one. Gramsci was in fact quoting French poet, novelist and dramatist Romain Rolland who Gramsci credited with the expression “pessimism of the intelligence and optimism of the will.” I think this is something close to a kind of hope that is an orientation to the world.

During the 1980s there was a long and very brutal Miner’s strike. Thatcherism and the logic of neo-liberalism was imposed harshly in a premeditated attempt to break the trade unions. The drama and trauma of this is remembered in countless films like Brassed Off and Billy Elliot. These films often contain figures who escape and for whom the story ends well – I’ve often wondered why the story of the strike needs a happy ending. Perhaps, it is in part because the breaking of the strike was such a total defeat.

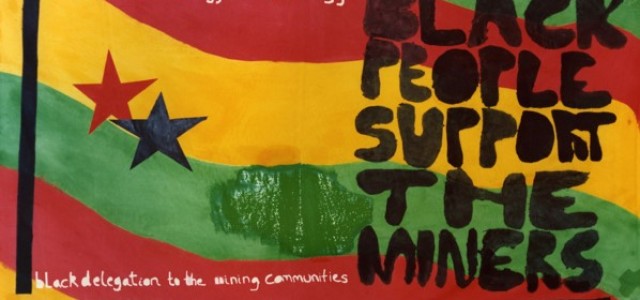

The Miner’s are iconic of the white working-class uncomplicated by empire, globalisation or immigration. It is interesting that these nostalgic films that are set around the strike contain not a single black or brown face. There is another moment that I want to think about in relation to my argument for a ‘sociology of hope’. It took place in Birmingham – Britain’s second city – a place where colonial guns were made and also a centre for concerns about mid twentieth century immigration. Enoch Powell gave his famous ‘river of blood speech’ in April 1968, and prophesized a race war in which the black man would have the whip hand over the white, from a hotel in central Birmingham. Powell has been somewhat recuperated in British public life as we edge closer to the 50th anniversary of his speech

There are no mines in Birmingham. However, striking miner’s received extraordinary amounts of support from within Brimingham’s black and brown communities. The Indian Worker’s Association organised highly successful fund raising events in a Handsworth pub. Sikh temples raised an estimated £5,000 – this was in stark contrast to the experience at churches including attempts to collect outside a Billy Graham rally that took place in Birmingham at the same time. Street collections on the Soho Road (a poor predominantly black and Asian district) were known to be amongst the best supported in Birmingham and miners squabbled over who should get that pitch.

I have been collecting the accounts of those Miners given to me by a friend. These pages of transcript are over thirty years old now. In them its becomes clear that many of the white Miner’s came to those areas of Birmingham with presumptions coloured by racism, but there was something in the overflowing of that generosity from the people of Handsworth and Lozells that was transformative.

“One person did a hell of a lot for me” said one of the Lea Hall Miners referring to an Asian student from the local Polytechnic. “He couldn’t do enough for you. I have seen him knock on doors, I never knew what he said, but I see the woman going in and fetch something out and he said something else and she went in again and the man came out and gave him 50p or something like that which is unbelievable. I don’t think I have ever been abused by anyone in the Asian community. Not saying “get out” you know. I’ve had it from my own people. But I class them more than my own now. That how much it has developed.” The Support Committee Minutes for the Cannock branch recorded: “Brother from Lea Hall reported that ‘they had a greater understanding of police harassment themselves now and would always support ethnic minority groups coming up against it in future as they were supporting the NUM so solidly now.”

There was another moment: an Island of hope. Four women at the Kewal Brothers sweatshop in Birmingham, where Asian women, earning as little as £1 per hour, had been sacked for joining the Transport and General Workers Union. Cannock miner’s, with barely enough money to feed their own families, hired coaches to take 150 Lea Hall and Littleton miners to the Kewal Brothers picket line.

Paul Mackney who wrote a history of the miner’s strike in Birmingham stressed how strong and transformative the solidarity shown by black communities had been for the miners. Many spoke of in terms of a kind of political realisation or epiphany, which had retuned their political sensibilities. On the 9th and 10th September, 1985 urban unrest broke out in Lozells and Handsworth these events were soon dubbed the ‘Handsworth riots’ even though they took place chiefly in Lozells. John Bates from Mardy remembered: “The Handsworth riots really excited me. I’d come to know the area. I was up all night with my radio listening, knowing some of the streets – the Soho Road, Lozells Road. It all flooded my memory, flooded back because I used to walk up and down those places.” This is a different kind of outpouring to the one that Enoch Powell prophesized in the notorious images of streets foaming with blood.

Paul Mackney comments that in September 1985 at an NUM rally in Stoke on Trent the Chair announced that copies of the Birmingham Trades Council booklet on the ‘Handsworth’ events were available. Long cues of miners formed eager to read news of what had happened and the response from within the local black communities.

Both strikes were broken, both failed, but in the midst of that failure was a transient and precious glimpse of a different kind of future in which the counter-intuitive – that alliances are forged across differences – becomes intuitive.

Hope is not a destination; it is perhaps an improvisation with a future not yet realised. It is not cruel optimism that hides behind a promise that is broken before it is even made. Hope then is an empirical question, and the sociology of hope requires an attentiveness to the moments when ‘islands of hope’ are established and the social conditions that makes their emergence possible.

Whose hope is this? Is it the male miner’s, the female sweat shop worker’s or is it the ethnographer’s? Ours or theirs? This is where I part company with the phenomenologists of hope who watch curiously the ‘rope that holds’. They claim to be beyond those ‘community day dreams’ animated by hope. I don’t think there is such a comfortable separation. That desire is an entanglement, a disposition that anticipates a hopeful sociology

References:

Berlant, L. (2007/8) ‘Cruel Optimism: On Marx, Loss and the Senses’, New Formations, 63 (Winter): 33-51.

Bloch, E. (1995) The Principle of Hope: Volume 1. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Camus, A. (2005) Summer in Algiers London: Penguin.

Desroche, H. (1979) The Sociology of Hope, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Lawner, L. (1975) Letter from Prison by Antonio Gramsci London: Jonathan Cape.

Lear, J. (2006) Radical Hope: Ethic in the Face of Cultural Devastion. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Mackney, P. (1987) Birmingham and The Miners’ Strike: The Story of a Solidarity Movement. Birmingham: Birmingham Trades Union Council.

Taussig, M. (2002) ‘Carnival of the Senses’. In M. Zournazi Hope: New Philosophies for Change. London: Routledge.

Terkel, S. (2004) Hope Dies Last: Making a Difference in an Indifferent World London: Granta.

Williams, R. (1989) ‘The Practice of Possibility’ in Robin Gable (ed) Resources of Hope: Culture, Democracy, Socialism London & New York: Verso.

Les Back is a Professor of Sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London. His recent books include: The Auditory Cultures Reader with Michael Bull (Bloomsbury, 2015) Live Methods with Nirmal Puwar (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), Cultural Sociology: An Introduction with Andy Bennett, Lauar Desfor Edles, Margaret Gibson, David Inglis, Ronalds Jacobs and Ian Woodward (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012). His forthcoming book Academic Diary: Or Why Higher Education Still Matters will be published by The Goldsmiths Press in 2016. He also writes journalism and has made documentary films.