Véronique Altglas (Queen’s University Belfast)

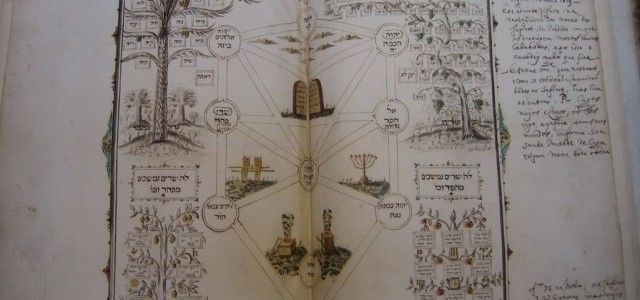

Why is it that Europeans and North Americans are so fascinated by the ‘religion of others’, evident for instance in the recent craze for kabbalah, as well as the popularity of yoga, meditation, shamanism and Sufism? It seems that their perceived otherness nourishes hopes for untouched sources of wisdom and hidden truths and yet, surprisingly, such attraction has not led to mass conversions to Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam or Judaism. Instead, these traditions are often explored as ‘bits and pieces’ that individuals combine in seemingly eclectic assortments of beliefs and practices. How can we understand people’s way of engaging with religious traditions that are initially foreign to them? Why and how have Euro-Americans become fascinated by these traditions? Why are some of traditions appropriated and not others? Does their popularisation require adaptation to new cultural settings and, if this is the case, what kinds of transformations do they undergo?

Surprisingly, while being a salient feature of contemporary religious life, this religious exoticism, as I want to call it, has not been investigated as such. Rather, sociologists of religion have insisted on the making of eclectic and personalised religiosities (what has been termed ‘bricolage’ after Levi-Strauss’ metaphor) as resulting from individualisation processes in advanced industrial societies.(1) In a world believed to have broken with tradition and historicity, it seems that individuals are emancipated from social norms and constraints and hence free to choose and combine religious resources of all kind, thereby crafting personal, and therefore unique, religious identities and belief systems. Hence ‘anything goes’, as Luckmann wrote about this bricolage of religious themes which, he argues, is more structured by ‘individual psychologies’ than social relations and factors.(2)

Researching new religious movements, which teach unconventional versions of Hinduism and kabbalah, and their followers (yoga and meditation practitioners, kabbalah students) led me to a very different understanding of the religious life of those who explore a wide range of beliefs and practices originating from different cultures. First, contrary to Luckmann’s stance, it is not the case that ‘anything goes’: the pool of religious resources that are appropriated is neither unlimited not arbitrary: the beliefs and practices that are sought tend to be rooted in traditions which have been understood as ancient, authentic, mysterious and vibrant alternatives to a disenchanted West. In other words, otherness is aestheticised before being appropriated; Hinduism, kabbalah, Sufism, Buddhism, Tantrism or Shamanism have been envisaged as absolute religious ‘others’, retaining what Euro-Americans believed their civilisation has lost. Undoubtedly, contemporary gurus or kabbalists instrumentalise exotic representations with subtlety and actively contribute to the making of idealized Eastern spiritualities and kabbalistic mysteries. Nonetheless, these idealized religious teachings have been elaborated and disseminated on the terms of those who appropriate them.

This actually presupposes the entitlement and power to do so. For example, representations of the ‘Mystical East’ that emerged in the nineteenth century were not independent of imperialist ideology and colonial practice in Asia.(3) Europeans had no interest in popular and contemporary religious life, which was seen as a degradation of Hinduism. Instead, they were looking for its so-called ‘golden age’, a pure Hinduism, which, it was imagined, would be found in its scriptures. A romantic orientalism was looking for untouched mysticism and truths, apparently dissolved by a soulless modern society. It was hoped that, by studying and knowing the ‘Mystical East’, European culture would be restored through rediscovering its ancient sources. Overall, the exoticisation of specific religious practices and beliefs can be understood as a way of conquering culture ‘from the inside’, through the interpretation, dramatization and exploitation of cultural differences. This entitlement to the culture and knowledge of others proved to be enduring. My interviewees who practiced yoga and meditation explained that ‘the West has lost it’ and look into these disciplines as sources of personal regeneration, explaining that things coming from ‘there’ interest them, because they could provide the ‘possibility of reaching something that we don’t have here’.

Secondly, pick and mix attitudes towards religious practices and beliefs are much less eclectic than is often assumed. As they spread transnationally, Buddhist masters, Indian gurus or kabbalah teachers increasingly came to present their teachings as universal sources of wisdom that transcend national, religious and cultural boundaries. This entailed downplaying the significance of rituals and core tenets, introducing new practices and engaging in interpretative discourses. The particularisms of these teachings are thus partly neutralised. Furthermore, Hindu, Buddhist, Kabbalistic, Shamanic or Sufi teachings have increasingly become homogeneous by drawing on ideas and methods deriving from popular psychology. The consequence of this has been that a single narrative is reiterated across a variety of practices – the existence of the self’s unexplored potential, the possibility and need to develop this potential, and the individual’s responsibility for inner change and life transformation. On the model of coaching and group therapies, these teachings are transmitted as self-realisation techniques, delivered through standardised classes and training courses. Accordingly, such standardisation of religious traditions limits the eclectic nature of individual religious trajectories. Besides, most disciples of yoga, meditation or kabbalah report no intention to practice Hinduism or Judaism and are largely indifferent to, and sometimes uncomfortable with, their Hindu and Jewish origins. Rather, they explore alternative religious resources with the aim of improving their lives by transforming themselves. Their incursions in yoga, meditation or kabbalah contribute to a quest which, again, despite its apparent eclecticism, is a fairly consistent ‘lifelong religious learning’ driven by aspirations to self-realisation.

This leads me to the third point in this article. Contrary to what many scholars assume, bricolage of religious themes is not evidence of individuals emancipation from social norms and structures. Indeed, there are striking correspondences between this form of religiosity, focused on self-realisation, and the type of selfhood demanded by neoliberal societies. The quest for self-realisation reflects social pressures upon individuals for permanent self-actualisation: flexible economies and the shrinking of the welfare state require that they become increasingly responsible for themselves and ‘freely’ pursue their personal interests. Neoliberal economies and polities therefore reward enterprising individuals who are willing to actualise themselves, who know how to manage their attitudes and develop new skills whenever the situation demands it.(4) In this context, the self has become the locus of the individuals governance. Religion does not escape from this social trend, although perhaps exoticised traditions, in particular, fuel hopes for the discovery of powerful techniques of the self. Indeed, the biographical discourses of students of yoga, kabbalah or meditation emphasise the paramount importance of ‘working on oneself’, a perception of life as a process of self-improvement and a sense of individual responsibility and voluntarism in this process of self-improvement.

Finally, through exploring why yoga and other forms of ‘other’ religious practices have become so enduringly popular, my research indicates that the practice of religious bricolage is not characterized by a simple emancipation of individuals from the old social structures, not least because class (and also gender, age and ethnicity) remains significant in the quest for exotic tools of self-realisation. ‘Spiritual seekers’ are mostly middle-class individuals for whom being flexible, ‘positive’, able to manage reactions, cope with stress, and develop harmonious relationships with others constitute a valuable type of emotional capital transferable in their social and professional environment. Those exploring exotic religious resources tend to belong to what Bourdieu called the ‘new petite bourgeoisie’ – therapists, artists or those working in marketing, advertising, public relations, fashion and design.(5) They are traders in symbolic goods and services and their predilection for ‘things foreign’ reflects the importance to them of accessing and controlling the circulation of apparently mysterious and distinctive symbolic resources. In so doing, these cultural intermediaries can display competence and maintain their role in the game of cultural and symbolic struggle. Constant exploration of diverse events and courses is therefore animated by the desire to discover new, apparently authentic religious teachings from those who are experts in personal growth, alternative therapies or ‘spirituality’. This new petite bourgeoisie represent a significant proportion of those I met through this research and who make use of these resources in their professional practice. In their case, religious exoticism can be understood as part of the continuous re-skilling of freelancers involved in competitive and unregulated markets of specific symbolic goods.

References:

(1) Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1966. The Savage Mind. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

(2) Luckmann, Thomas. 1979. “The Structural Conditions of Religious Consciousness in Modern Societies.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 6: 121-137.

(3) Inden, Ronald. 1986. “Orientalist Construction of India” Modern Asian Studies, 20/3: 401-446.

(4) Rose, Nikolas. 1998. Inventing our Selves: Psychology, Power, and Personhood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

(5) Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Véronique Altglas is Lecturer in Sociology at Queen’s University Belfast. She has conducted research on the transnational expansion of neo-Hindu movements and kabbalah, the management of minority religions in France and Britain, and anti-Semitism. This article draws on her last book, From Yoga to Kabbalah: Religious Exoticism and the Logics of Bricolage (Oxford University Press). It addresses issues of exoticism and bricolage in religion, through cross-national research among Hindu-based movements in France and Britain since the mid-1990s, and more recently on the Kabbalah Centre in France, Britain, Brazil and Israel.