Charles M. Payne (University of Chicago)

It was inevitable that the demonstrations following police killings around the country would draw constant comparisons to the protests of the Sixties. Given how poorly Americans understand that history, it was just as inevitable that most comparisons would fall somewhere between awkward and completely off-base. Consider the comments, from people of all colors, that these demonstrations won’t do any good, they are only cathartic, the demonstrators are disorganized, don’t know what they want or how to get it or they just want attention for themselves or their own causes, innocent people shouldn’t have their lives disrupted, the timing isn’t right. So on and so forth. Comments like these seem to function as armor, as a buffer against actually thinking about the issues that generated the demonstrations.

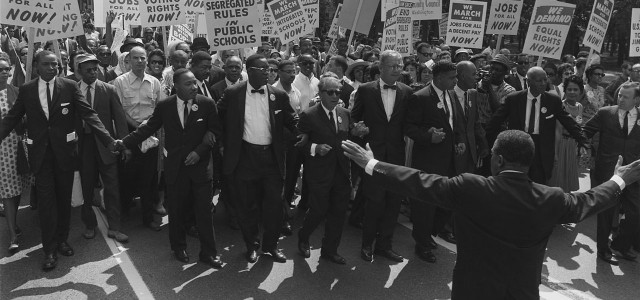

Americans have largely forgotten that the protests of the Sixties took place in the same atmosphere of dismissal. Consider the 1963 March on Washington, arguably the most iconic demonstration of the period, remembered now as a moment of inspiring national consensus. At the time, it was a bit more complicated. In June of that year 57% of Americans responding to a Gallup poll –70 % in the South — said that demonstrations hurt the Negro’s cause more than it helped. The week before the march, 63% of those who knew about it had unfavorable feelings about it. Among them, 17% volunteered that “it won’t accomplish anything.” Let us note, too, that in 1963, before any major Civil Rights legislation had been passed, fully 43% of Americans thought Negroes had as good a chance to get any job they qualified for as whites. It was 1963 and we were already post-racial!

As much as they are lauded today, the Freedom Rides of 1961 generated a storm of controversy at the time. The Kennedy administration chastised the riders for embarrassing the country in the eyes of the world. Robert Kennedy, the Attorney General, framed one of his calls for a “cooling off” period, by noting that ‘Besides the group of “Freedom Riders” traveling through these states, there are curiosity seekers, publicity seekers, and others who are seeking to serve their own causes….’ He pronounced his opinion that his Department of Justice could not pick sides in a Constitutional dispute, leading many to ask what purpose it served then. Only 24% of the nation approved the Rides. Two years later, President Kennedy referred to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which had continued the rides after they met violence in Alabama, as S.O.B.’s with an investment in violence.

Martin Luther King, though much less aggressive than the young people of SNCC, was still constantly faced with charges of trying to push too fast. His ‘Letter from a Birmingham Jail’ was a response to those who thought the demonstrations ‘untimely and unwise’: ‘You deplore the demonstrations taking place in Birmingham. But your statement, I am sorry to say, fails to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about the demonstrations. I am sure that none of you would want to rest content with the superficial kind of social analysis that deals merely with effects and does not grapple with underlying causes. It is unfortunate that demonstrations are taking place in Birmingham, but it is even more unfortunate that the city’s white power structure left the Negro community with no alternative.’ The movement’s greatest stumbling block, he added, might be those more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice.

Those who say protestors don’t always articulate clear demands are exactly right but they are missing the larger point. A few months after working in the Mississippi movement, Mario Savio said, in a speech at Berkeley that became one of the touchstones for a generation:

There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious—makes you so sick at heart—that you can’t take part. You can’t even passively take part. And you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all.

Sometimes, people need to be in motion before they can figure out direction. Sometimes, just screaming one’s disgust with the status quo is enough to make some difference. Some of the concessions elites made in the Sixties were made because they thought society was falling apart, not because they were responding to some set of carefully-thought-out demands. .

The sociologist Herbert Haines captured some of this in his book Black Radicals and the Civil Rights Mainstream, 1954-1970 (1988). According to Haines, the country flatters itself by constructing a past in which civil rights victories were the product of nonviolent appeal to conscience. In fact, the data suggest that donations to civil rights organizations and concessions to them increased after periods of urban rioting. The movement’s radical flank made the demands of centrists seem reasonable. Malcom X understood this dynamic very clearly and relished his role and the scary alternative. That was the spirit in which he went to Selma in 1965.

Another common misuse of history involves fundamental misunderstandings of what the movement was trying to do. A case in point would be the column by David Brooks in the New York Times (December 1, 2014) which begins by suggesting that others don’t understand the civil rights movement and proceeds to demonstrate that his own understanding is less than firm, including this bit of confusion: ‘During the civil-rights era there was always a debate about what was a civil-rights issue and what was an economic or social issue. Now that distinction has been obliterated. Every civil-rights issue is also an economic and social issue. Classism intertwines with racism.’

The implication that civil rights could ever have been separated from economic progress is a very poor way to capture African American aspiration after World War II. They were inseparable. As far back as 1944, Gunnar Myrdal made it clear that the first priority for African Americans was economic progress. The formal name of the 1963 march was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and the speech by SNCC’s John Lewis at the march pointed out that civil rights bills didn’t do anything about economic disparities. March demands included a national program of full employment with ‘meaningful and dignified’ jobs at decent wages, a 75% increase in the minimum wage, a broader Fair Labor Standards Act, a bill against job discrimination at all levels.

Many of those goals are depressingly relevant still. Similarly, I’m sure many veterans of that movement cannot see banners proclaiming ‘Black Lives Matter’ without painful memories of other Black lives lost to the indifference or collusion of law enforcement officials and Ella Baker’s pronouncement that, ‘Until the killing of black men, black mothers’ sons, becomes as important to the rest of the country as the killing of a white mother’s son, we who believe in freedom cannot rest until this happens.’ In an activist career that spanned most of the 20th century, Miss Baker played important roles in nearly all the major civil rights organizations and in countless smaller ones, she was crucial to the founding of SNCC, which became the cutting edge of the Southern movement and she nurtured some of the most important young leaders of that generation.

The specific context of that remark was the 1964 Mississippi Summer Project. This year, I was frequently dismayed, following some of the 50th anniversary commemorations of the summer, that some of them failed to convey perhaps the most essential point about it: that the summer was necessitated by the national devaluation of Black life, by the pervasive unwillingness of law enforcement agencies, or political leaders or media to react to the killing of civil rights workers or citizens as long as they were Black. The commemorations of the summer reenacted the racial dynamics that had made the summer necessary, many years and lives ago.

Like many others, I think of Miss Baker as Eldest and Wisest. It is good to remember her at times like these because she brought the view of someone who spent a lifetime in struggle. For one thing, that means she knew that people could change, that some of the same people in the Deep South who in 1962 referred to the movement as ‘dat mess’ and to civil rights workers as fools and worse, would themselves become staunch movement leaders. (And Bobby Kennedy lived long enough to change.) Some of the people who are standing on the sidelines and criticizing now will themselves be in the streets after the next killing.

Charles Payne teaches in the School of Social Service Administration at the University of Chicago and is the author of I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (University of California Press, 1996).