Photo: © Dean Weston

Dariusz Gafijczuk, Newcastle University

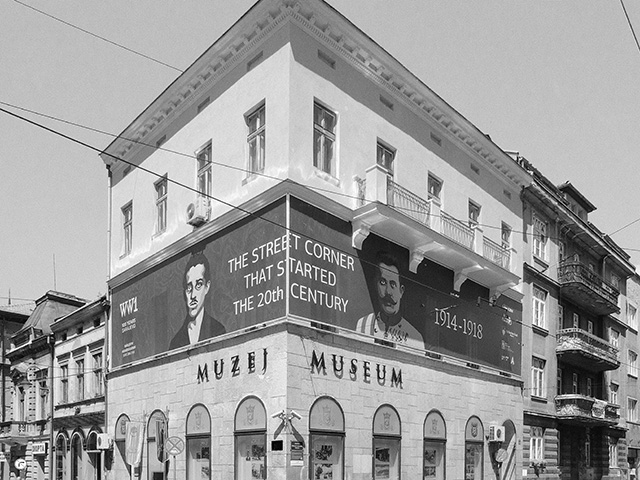

It’s Saturday, 28 June – exactly 100 years to the day after the Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie were shot dead. A large banner wrapped around the upper stories of the City Museum right at the corner where the shots rang out, proclaims: ‘This is the street corner that started the 20th century.’ A replica of the Gräf & Stift automobile is parked right in front, almost exactly on the spot their car must have been after it mistakenly turned, instead of continuing straight along the Miljacka river to the railway station.

It’s a warm day. The limousine sits on what is now called Zelenih Beretki or the Green Berets street, harking back to the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s, adding yet another layer to the cultural geology of memory in this place. The green khaki sheet metal in which the car is clad overheats in the sun – two actors dressed up as the Archduke and his wife sit at the back in period garb. Tourists take pictures, minor dignitaries lay wreaths at the wall, amateur history buffs pose, occasionally exchanging places with one of the official impersonators, donning the hats, smiling for posterity. History is a carnival of endless paradoxes. That evening there is a Vienna Philharmonic concert to add pomp, song, and wine to it all. As I write this I’m sipping coffee out of the ‘Gavrilo Princip’ coffee mug I picked up at the museum. It says: ‘WWI 100 Years Sarajevo’ with the assassin’s prison mug shot from Terezín – at that time still a dilapidated, provincial detention facility.

I had arrived in Sarajevo a few days before for a conference entitled “The Long Shots of Sarajevo: Events-Narratives-Memories of 1914”, one of many surrounding the centenary ‘celebrations’. It turns out to be a very successful event, as such things go, but something grates at me throughout. I can’t shake the feeling that all this somehow misses the point, that the entire idea of marking, commemorating, celebrating, or even critically analyzing what, by all accounts, still remains a controversial historical event, imposes a false identity on the passage of time itself. Or to put it a different way, imposing a commemorative frame as has been done with WWI (and there are many such events still to come, especially in the UK) is remembering under the pressure of expectation to do so. That sort of engagement distorts as much as it educates or pays respect, if this is indeed what is at stake.

I am not talking about forgetting or deliberately ignoring history, but about something like the ‘natural process of wearing away’; an unobstructed crumbling of memory (which occurs anyway) that rebalances remembering, making it an integral part of our active perception of the world around us, instead of encasing it in the dead weight of time, by casting it as the traumatic, or glorious, heroic and sacrificial past. I am making a distinction here between the spectacle of commemoration and the cultural psychology of remembrance. The former is like slapping a bit of paint on a rusty fence. The later is a grinding, visceral labour that changes physically with our bodies and with the material constitution of cultural affairs. There are plenty of cold, hard facts in that short 20th century which should never be forgotten. But their remembrance – to do justice to a moment that was once someone else’s life and death – must be continually renewed and reanimated and will change with each and every renewal. Therefore remembrance is a much more arduous process than the industry of commemoration would have us believe.

It is not only our psychology but urban and cultural spaces that mould themselves according to, and follow the dynamics of such a process. Sarajevo lends itself especially well to such an engagement, given that it is only twenty years removed from a real and devastating war, not a hundred years past a war that, in actual fact, brought no real fighting to Bosnia. In the remainder of this article, I would like to reflect on this fact and offer a few more observations in the spirit of time and remembrance as the space of the city made them available for an encounter.

“Sarajevo: the Heart of Europe” is the official slogan of the centenary commemorations. And all of Europe is here again. The French sent a large team of civil servants, administrators and cultural attachés under the umbrella of Mission du Centenaire, winning the EU mandate to coordinate the commemorations. According to the proposal, “for a few weeks around the symbolic date of June 28th it [Sarajevo] will be the Heart of Europe”.

But I think Sarajevo, the unconscious of Europe would be a much more accurate description. Inadvertently, some old geopolitical wranglings, this time in a minor key, are replayed behind the scenes. The Serbs, on the other hand, hold their own events, in places like East Sarajevo and Višegrad unveiling new monuments and statues to their eternally youthful hero. Someone floats the idea of reconstructing the memorial to Franz Ferdinand and Sophie, removed in 1918. And the complex vitality of the past is reduced again to crude quarrels over stone and bronze monuments, while, as the Bosnian host of our gathering Vahidin Preljević, points out “critical culture of memory, which does not lionize or demonise”, is still missing. Such culture depends on the ability to perceive multiple layers of time and history simultaneously – being attuned to their tensions and contradictions. Anything less is an unwarranted short-cut.

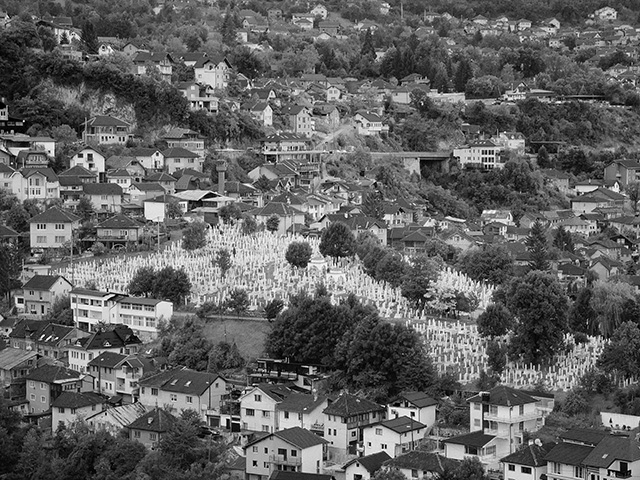

In a place that compresses space and time ‘for a living’, so to speak; in a city that doubles, triples, even quadruples existence by folding in upon itself many times over, there can be no short-cuts but only perpetually decaying and self-renewing zones of engagement. These extend from the surrounding hills, through the traditional neighbourhoods (mahalas) that climb their slopes stitched together by graveyards, to the city streets down below and the spider-web like transparency and resilience of the old Turkish market (Baščaršija) – the nexus of life since the 1460s when the Ottomans ruled these parts for over four centuries. Sarajevo had been thought of as the Jerusalem of the Balkans – the cradle of religions. Its dramatic geography is matched by a polyglot identity, a mixture of Islam, Christianity (in all its variants), Judaism – a veritable cultural and existential mush. At one time or another, the spoken languages included Turkish, Arabic, Persian, Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, Magyar, German, Italian, with all the variants in between. We think of this as an exceptional state of affairs, but in fact, if one looks at world history more comprehensively, such polymorphous reality, is history’s most constant variable.

No, there can be no short-cuts here. This is what Sarajevo shares with the rest of Central Europe – a Europe which, like an organ donation, was transplanted here by the already terminally ill Hapsburg Empire in the latter half of the nineteenth century, starting in the 1870s, when Bosnia-Herzegovina fell under the protectorate of Vienna, continuing through its annexation in 1908 and the events of 1914. Today it not only remains a part of Europe, but more profoundly, this is where the unconscious of Europe found its dwelling, because Sarajevo is continually identified as the place ‘where it all started’. This is how, paraphrasing Dzevad Karahasan (2010), Sarajevo became a microcosmic model of the world, its centre, because its multiple enclosures force Sarajevo “to look into itself”, opening up an interior that is limitless, like the unconscious. The topography of this city lends itself especially well to a continually exposed interiority of life – perhaps this is the blessing and the curse of its now vibrant, youthful, even care free attitude. But Sarajevo has once more come full circle, living an identity as an inhabited ruin; not as something merely negative but, as I have argued elsewhere, “a process of ruination, which also allows the past to emerge in the moment of our encounter with the ‘afterlife’ of various events”. This is the point where remembrance, as a form of life, can begin taking hold.

My encounter with Sarajevo was like seeing “ghosts in the sunlight”, with life casting the long shadows of its interminable renewal in front of its past. There was a sense of sadness and promise mixed together, like the promise of a departure in the largely disused Sarajevo railway station. There are only a few trains a day coming and going now. The terminal is a far cry from its former hustle and bustle – the last daily connection to Belgrade was suspended a year or two ago. Still, there is something graceful, even welcoming about this space – its high modernist pride worn but unbending. It is a promise intrinsic to the very possibility of movement, even as the past treads heavily on its worn out tracks.

Photo: © Dean Weston

Outside the terminal, one crosses a square, its marble paving stones arranged in a lattice-work pattern. It is now ‘The Square dedicated to the Victims of the Genocide in Srebrenica” – strangely isolated, almost innocuous, fronting the now largely deserted building. But emptiness is misleading. The past never disappears. It only changes its physical state, from solid, to liquid, to vapour, to ink, to blood, to stone – and on and on – making it more or less accessible, and sometimes not at all. But this temporal morphology has little to do with commemoration.

In the end, perhaps the only thing that can be said with any certainty is that “time kept its word (it always does)” (Zagajewski 2009).

References:

Karahasan, D. (2010) Sarajevo Exodus of a City. Sarajevo: Connectum.

Zagajewski, A. (2009) Eternal Enemies. New York: Farr, Giroux, and Strauss.

Dariusz Gafijczuk is Lecturer in Sociology in the School of Geography, Politics and sociology aat Newcastle University. He is author of Identity, Aesthetics and Sound in the Fin-de-siècle: Re-designing Perception (Routledge, 2013) and co-editor (with D. Sayer) of The Inhabited Ruins of Central Europe: Re-imagining Space, History, and Memory (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).