Sue Scott, University of York

Discover Society is modeled on the magazine New Society (1962-88) and one of its aims is to explore themes that are as pertinent now as they were 50 years ago, to this end I have been looking at past issues of the magazine. In June 1964, just 4 months after the release of Dylan’s then confident refrain – and a year after sexual intercourse began, according to Phillip Larkin – James Hemming (see endnote) published a piece in New Society entitled ‘What is truth in SEX?’. Hemming argued that ‘in place of the old taboo sexual morality, a new, rational system of relationships between the sexes stresses maturity of personality’. He went on to suggest that in the early 1960s ideas about sexual relationships were polarized between the ‘emancipationists’ and the ‘moralists’ over the vexed question of ‘when a man and a woman should be allowed to go to bed with one another’.

Who should be allowed ‘to go to bed with whom’ continues to be a matter for debate despite the fact that we have, in the main, moved away from such coy terminology, but Hemming was writing in the aftermath of a significant example. In 1963 the Profumo Affair rocked the British public’s trust in its politicians not for the first, or the last time. It was seen as a sign of the times at the time and, retrospectively, was judged to resonate with an emerging Zeitgeist. For me, as a 10 year old, it was one of my earliest memories of sex, almost, but not quite, speaking its name in public – I knew something was going on that I wasn’t supposed to understand and unsuccessfully tried to match the pieces of blue sky to the more exciting bits of the jigsaw without having access to the picture on the box!

From Taboo to Modernity

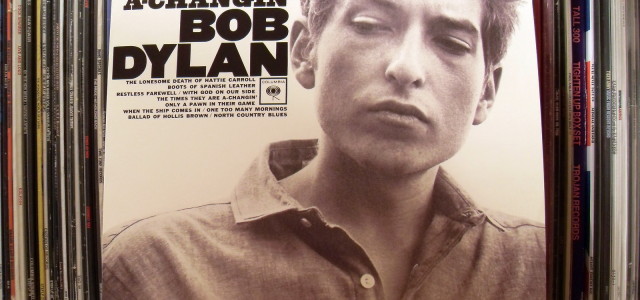

Hemming’s article contrasts the sexual mores of the early 1960s with those of fifty years earlier. On discovering this piece I found it impossible to resist attempting to bring the story up to date – fifty years on. I don’t think there would be many detractors from the proposition that sex continues to occupy a very significant place in both public debate and private experience, but how much has our relationship to it changed? Hemming’s piece has all the confidence of Bob Dylan’s lyrics in that he is a thoroughgoing modernist who thought things had improved and expected them to continue to do so. He lists the ‘gains’ made over 50 years as he sees them as follows:

- There has been a steady decline in prudery. Although pockets of resistance persist in some of our sub-cultures, most of us are now prepared to expose ourselves to sun or sea, when the opportunity offers, almost naked and quite unashamed

- We now regard our bodies as a fully legitimate source of pleasure and are prepared to give them the attention and appreciation they deserve

- Sexual fulfillment is now regarded, not as a suspect pleasure, but as a source of mental health

- It is now recognized that creative vigor is not necessarily the product of suppressed or sublimated sexuality; it may well be the outcome of a happy sexual relationship

- Woman today has a more important place in society, and is more highly valued as a person, than she was 50 years ago. One sidelight of this emancipation is that she is now expected to experience physical passion. In 1913 the sexually alive woman was encouraged to regard herself as not quite nice. Today it is apprehension of frigidity which is more likely to cause a woman concern

- Birth control, formerly something quite unmentionable in decent society, is now accepted by the majority and discussed without embarrassment

- A cruel, intolerant attitude to divorce has been modified to sympathetic regret, except among our more condemnatory personalities

Hemming was trained as a developmental psychologist and offers us an insight into the relationship between this theoretical framework and the wider notion of a linear motor of modernity. He does nevertheless allow that the line of progress doesn’t always run straight and enumerates some losses as the flip-side to the gains. He sees the new emancipation as heralding a new set of anxieties resulting from the implication that ‘sexual ecstasy was available for all who would master the techniques of love’. He criticizes the ‘how to’ books of the time for over stressing physical skill and standardized procedures. This resonates with what I, some years later, called the ‘Taylorisation of sex’ (see Scott and Freeman1995 and Jackson and Scott 1997). He also criticizes the pressure to produce simultaneous orgasms and the increase in the commercialization of sex – via advertising. However, he sees these issues as simply ‘growing pains in a movement within society towards healthier sexual attitudes’. Hemming goes on to predict that within the next two decades divorce on grounds of incompatibility and homosexual relationships between consenting adults would become legal and that there might also be abortion law reform. All of which came about, to a greater or lesser extent, more quickly than he anticipated.

Hemming discusses what he describes as ‘the awakening to the significance of the sexual relationship in human development’. He argues for a rational morality founded on human nature and the needs of society, rather than on an outdated ‘taboo system’. Hemming anticipated continued clashes between the developmental approach and the taboo system, but thought a ‘choice’ had to be made based on an evaluation of the quality of relationships rather than on an outmoded belief system, based on value judgments. He was, it seem to me, anticipating what Anthony Giddens, writing almost 30 years later, called ‘the pure relationship’. At the core of Hemming’s position is a qualitative evaluation of the practical experience of sex, and a case for a pragmatic approach to legislation, sex education and personal behavior.

He stresses the importance of society over the individual accepting that, without rigid moral constraints, some people would behave badly but seeing this as a risk worth taking for the sake of overall societal gain. He allows that some individuals will fail to respond to this new way of behaving, but dismisses this by analogy stating that, just as we should continue to build better roads even though this will give ‘irresponsible’ drivers the opportunity to drive dangerously, so society needs to be more open about sexuality and to increase levels of sex education for the long term greater social good. In making the case for sex-education he argues that this increased openness will not be a threat to marriage, but rather this emphasis on the quality rather than the incidence of marriage will ‘raise the quality of sexual life in society and make marriage much more than a license to copulate’

Fifty Years On

To some extent Hemming fell into the trap of assuming that what he saw in the light from the lamppost he was standing under was happening in the rest of the street, and indeed the rest of early 60s Britain. We have all heard the old adage that if you remember the 60s you weren’t there, but of course many of us do remember the 60s, it’s just that we weren’t all swinging – or not much. The pill existed, but wasn’t available to the unmarried in 1964 and unmarried mothers were still being sent away to ‘homes’ to have their babies who would then be taken away. Abortion was illegal as was male homosexuality – lesbians of course didn’t exist! Since the 1960s we have had Feminism to show us that the ‘emancipatory’ trend is very slow moving, and Foucault to explain that sex was not something that could simply be modernized and that with change would come resistance from different directions. Sociologists have taken on board, via Post-Modernism, the critique of the linear progressive model of social change, although sometimes we forget and extrapolate from what we can see in the light cast by our particular lampposts.

Hemming argued strongly for open sex education that went beyond the biological basics, but sex education offers a good example of how contested sex continues to be. For example, it was acceptable for my Sixth Form Council, in 1971, to discuss the possibility of installing a condom machine in the common room, (although it didn’t happen!), but when I raised this issue, in research interviews, with Head Teachers 25 years later they were aghast that it should even be thinkable. Then there was Clause 28 and the debate about the dangers, versus the necessity of sex education, which continues today. We still worry about children having access to too many pieces of the jigsaw too soon and still fail to give them the box with the picture on it (Jackson and Scott 2010). The truths of sex continue to be played out on a contested moral terrain and in Britain today we are caught between the expansion of commercialized sex and public anxiety about sexualisation (see Jackson and Scott 2015). Both of these tendencies continue to define sex as special, and somehow separate from everyday life, rather than as part of everyday routines and practices.

Yes, there has been liberalizing legislation since 1964, in relation to abortion – although this continues to be contested, in relation to censorship and especially in relation to homosexuality. Although with regard to the latter, despite the undoubted gains, the legalization of gay marriage is also part of an extended neo-liberal project where individual rights are offered in the support of a particular kind of citizenship that prioritizes the monogamous couple (see Heaphy in Discover Society 6).

Something that has changed very little, despite much debate, is the lack of success in getting convictions for rape and ‘routine’ sex crimes against women. This can be set against the current media and legal circus around high profile sexual predators such as Jimmy Savile (see Cree et al in Discover Society Issue 4) and their ‘child victims’. Given that any link between childhood and sexuality is seen as antithetical, anxieties are raised up by the current practice of extending the definition of childhood, thus to defining more ‘victims’ as children -extending the definition of childhood and keeping children ignorant about sex, in order to maintain their innocence may well render them more vulnerable (Jackson and Scott 2010). Especially interesting is the current tendency to view the past (in these cases usually the 1960s and 1970s) through the prism of the present to the extent that, in order to increase the enormity of the crimes, differences in perceptions about the span of childhood, then and now, are forgotten. Also forgotten is the everydayness of ‘sexual harassment’ to which young women were subject, but in the 1960s had no language to name. This is the terrain on which the past behavior of ‘media personalities’ and others needs to be located. I make this point to stress the importance of understanding sex within particular social, historical and cultural contexts.

Sex and the Social

One of the things which interests me about the Hemming article is his focus on the social as well as the individual implications of sexual behavior, and how this focus differs from the much more individualized discussion of sexuality today. For me as a sociologist, sex is always social – embedded in contexts of gender, class, sexuality etc. and despite what some theorists would suggest sex does not float free from the embodied everyday, but rather is part of our ordinary daily lives. This is how we need to understand sex that is defined as unacceptable as well as the ‘nice’ kind. In my view Hemming overestimated the changes over the 50 years to 1964 and this tendency has persisted. I would suggest continued caution in relation to ‘overestimating change at the expense of being aware of continuities – particularly the persistence of gendered power relations – and against too celebratory an account of those transformations that have occurred, while noting the ways in which the boundaries of the normative are being redrawn and new tensions in sexual life are emerging’ (Jackson and Scott 2010).

References and Notes:

Jackson, S. and Scott, S. (1997) Gut Reactions to Matters of the Heart: Reflections of Rationality, Irrationality and Sexuality in Sociological Review 45(4) 551-575

Jackson, S. and Scott, S. (2010) Theorising Sexuality, Open University Press, Maidenhead

Jackson, S. and Scott, S.(Forthcoming 2015) in E. Renold, J.Ringrose and D. Egan (ed.) Children, Sexuality and the Sexualisation of Culture, Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke

Scott, S. and Freeman, R. (1995) Prevention as a Problem of Modernity: The example of HIV and AIDS, in J. Gabe (ed.) Medicine, Health and Risk: Sociological Approaches. Oxford:Blackwell

Dr. Clifford James Hemming 1909 – 2007, was a British child psychologist, educationalist, teacher, activist and humanist. He appeared as a defence witness in the Penguin Books obscenity trial of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, in 1960, and campaigned for better sex education in schools.

Sue Scott is a sociologist. She is Honorary Professor in the Centre for Women’s Studies at the University of York, Honorary Professorial Fellow in Sociology at the University of Edinburgh and Visiting Professor at the University of Helsinki. With John Holmwood she is founder and Managing Editor of Discover Society. She has published widely on sexuality, gender risk and childhood and sex education, often with Stevi Jackson.