Kieran Connell and Matthew Hilton, University of Birmingham

On Monday 10 February, Stuart Hall, one of this country’s few public intellectuals, died at the age of 82. Hall was a pioneer in the field of cultural studies, and his political interventions also saw him become one of the chief intellectual critics of ‘Thatcherism’ – indeed, he coined the phrase even before she became Prime Minister.

Hall had arrived at Oxford University to read English on a Rhodes scholarship from Jamaica, but left academic life – and an incomplete doctoral thesis on Henry James – to become a key player in the New Left and the founding editor of its magazine, the New Left Review. Hall also began teaching media on adult education courses, co-writing a book on the subject with his friend and colleague Paddy Whannel. It meant that when in 1964 an invitation came from Richard Hoggart to join his newly-established Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at Birmingham, Hall was ideally placed to assist the project in its research into youth cultures, the press, film and television.

The Centre was funded in part by Penguin Books in recognition of Hoggart’s star performance in the Lady Chatterley’s Lover obscenity trial. Hoggart wanted the initiative to expand on The Uses of Literacy, his earlier book on working-class cultures and the mass media, and to study everyday forms of popular culture using skills drawn from literary scholarship. The bulk of Penguin’s annual grant of £2,500 went on employing Hall as a full-time Research Fellow on the project. Hall brought a sophisticated theoretical grounding that marked the Centre as the institutional origin of cultural studies. For Hall, cultural studies was never a discipline in itself, but a field of enquiry, a mechanism to understand the broader structures that shaped our everyday lives. His most famous works while at Birmingham included analyses of how meanings are transmitted and received in the media (‘encoding’ and ‘decoding’) as well as how identities based on age, class, race and gender intersected with dominant ways of seeing.

But beyond his own insights, Hall’s work at Birmingham was distinctive because of the practices of research and collaboration he instigated, particularly when in 1970 Hoggart departed for UNESCO and Hall assumed the position of Centre Director. Inspired by the political fervour of the rebellions of 1968 and the work of the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, Hall sought out new working practices for teachers and students that attempted to break down traditional academic hierarchies. Decisions relating to the intellectual direction and administrative organisation of the Centre were undertaken collectively; students sat on interview panels for prospective students; and an unofficial hardship fund was set up, taken from all Centre members who earned a salary and allocated to those who were in need of financial assistance.

Even if such practices could not be widely publicised at the time, the Centre became famous for a collaborative model of intellectual work that was more in keeping with established practice in the sciences than the arts. A series of co-written books, articles and ‘working papers’ that explored topics such as subcultures (Resistance Through Rituals), race and the law (Policing the Crisis) and the theoretical aspects of cultural inquiry (Culture, Media, Language) made the ‘Birmingham School’ – as the Centre came to be known, much to the chagrin of Hall and others – an academic ‘brand’ that continues to be recognised around the world. Many of Hall’s graduate students never got round to submitting their PhD theses, so busy were they in publishing joint ventures with their peers and teachers. Such was Hall’s intellectual generosity that, unlike almost every other leading intellectual working in the arts and humanities, he never published a monograph on his own. His ideas were there to stimulate and provoke; to join a conversation that others would take up.

There were, of course, difficulties to this project, not least in terms of the Centre’s relationship with wider university management at Birmingham. The Centre and Hall played an active role in a major student protest that took place on campus in 1968 over the issue of student democracy and representation in university decision-making. Hall addressed the sit-in and publicly criticised what he saw as the repressive nature of existing university structures. Hall’s visible support for the students marked his card for many years and ensured he was never offered a chair at Birmingham. It also contributed to the lack of investment in the Centre throughout the 1970s – what is perhaps most incredible is that the tremendous outpouring of empirical research and theoretical reflection in this period was achieved with a permanent staff of just two or three lecturers. Hall got the best out of his colleagues and raised the bar for what could be achieved by graduate students.

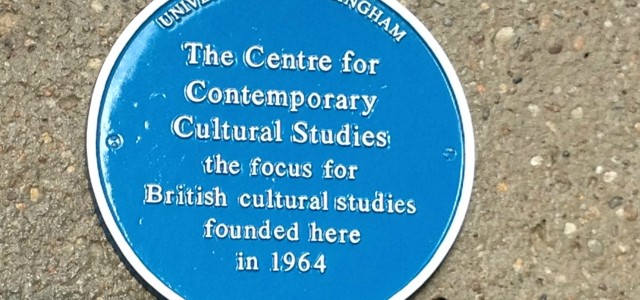

Given the University of Birmingham’s earlier hostility towards Hall and the Centre there was an irony to its decision in 2011 to include the Centre in its Blue Plaque scheme in celebration of ground-breaking academic work undertaken at Birmingham. When Centre alumni visit campus they often take photographs of the plaque which, in a further irony for a tribute to a body of work so influenced by various strands of Marxism, is housed next door to a Starbuck’s coffee shop. But there is also a certain fittingness to the plaque honouring the Centre as a collective enterprise rather than the sum of individual efforts. This underplayed Hall’s own key contribution to its development, but it reflected perfectly the spirit of inquiry and debate that Hall injected into his and his colleagues’ work.

There were other difficulties within the Centre’s collectivised experiment. Hall himself at times struggled to reconcile his commitment to the ethos of 1968 with the politics of academic hierarchy. He was twenty years older than many of his collaborators and, as one colleague put it, always ‘the cleverest person in the room’. His commitment to the ongoing project of cultural studies was obvious, but he also wanted to allow the space for those with different ideas to develop it in alternative directions. Hall often found he was criticised just as much for staying silent in discussions as for speaking too much. In the political fervour of the 1970s each new cohort of students arrived at the Centre with a new set of political battles ready to be fought, often over the increasing centrality of various forms of identity politics. Hall, he recently admitted in an interview, began to find he ‘couldn’t manage the transition between being their Director, their supervisor, their friend, their political ally, their intellectual interlocutor’. Exhausted, Hall left the Centre in 1979 to take up a post at the Open University where his publicly available lectures on the BBC inspired an even wider group of students.

The breadth of Hall’s influence was illustrated in the aftermath of his death by the range of people operating in very different sections of society who were moved to pay tribute to his life – from the political activist Tariq Ali to the feminist writer Suzanne Moore, the filmmaker John Akomfrah and the Labour politicians Diane Abbott and David Lammy. At Birmingham, Hall’s achievements had been acknowledged with the award of an honorary doctorate in 2000, though relations were soured again in 2002 when what had become the Department of Cultural Studies and Sociology was controversially closed by the University, in spite of an international campaign to save it.

In recent years, though, Hall had become an active supporter of the creation of an archive of the work of the CCCS and many of its leading figures. This is currently being created in the University’s Cadbury Research Library (fittingly housed in the basement of the Muirhead Tower in which, on the 8th floor, Cultural Studies resided for many years) and will be added to by Hall’s own papers. Hall’s achievements, influence and legacy – bound up as they are with the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Studies for a crucial part of his career – will also be marked by a conference and exhibition this summer, to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the Centre’s foundation. It was perhaps characteristic of Hall’s extraordinary generosity that one of the final pieces he worked on – in between being hospitalised with a serious illness – was the foreword to the catalogue that will accompany the exhibition.

Kieran Connell is a Research Fellow in Modern History at the University of Birmingham. Matthew Hilton is Professor of Social History at the University of Birmingham.

The conference marking the 50th anniversary of the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies will feature a video interview with Stuart Hall recorded last year. The conference will take place at the University of Birmingham on the 24 and 25 June. For more information please visit: www.birmingham.ac.uk/cccs

’50 Years On: the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies’ will open at the Midland Arts Centre on the 9th May. See www.cccs50.co.uk for more details.