Ruth Graham

Thinking about how the concept of meritocracy relates to contemporary times gave me an opportunity to reflect on what might be considered the everyday privileges of working in higher education. Going to university in the early 1990s offered me a chance to use Young’s meritocratic combination (effort and intellect) to enhance my life (and my earning potential). This potential resulted in a professional career that I had never anticipated, in higher education itself.

Twenty five years on, I find I must balance this sense of good fortune with a higher education sector facing significant resourcing challenges. Ongoing debates about the sector’s over-reliance on casual contracts, appropriate resource models to fund pensions, and fair wage levels are an indication of a broader sense of unfairness in how resource allocation plays out for those working in higher education. These issues require critical reflection, and proactive engagement with these issues in the scholarly community is heartening. And yet, when I think about my own experience of working in higher education, I still feel like I won some kind of lottery, which makes it hard for me to feel hard done by. I offer these personal reflections on my attempts to make sense of meritocracy in my work as an academic social scientist.

My engagement with higher education began as an undergraduate student of Social Policy in the early 1990s. This multidisciplinary field focuses on questions of inequality and social exclusion, so from the start inequality was centre stage in my higher education experience. And from the start, it was clear that those in the middle classes tended to gain most from the universal provisions of the welfare state, like education [1]. By the early noughties, I had my PhD and was working as a junior researcher with medical sociologists as well as teaching public health. Working in this area of scholarship reinforced the view that it was the affluent who experienced significant advantages in terms of both health care and health outcomes. These critiques are hardly new, and it is important to acknowledge that universal models of provision offer political stability to welfare provision that really matters to the most disadvantaged[2]. Health care provision cannot possibly resolve all of the inequalities that stem from poverty and disadvantage and it is unfair and unrealistic to expect this of the NHS and, similarly, education. Against this intellectual backdrop, arguments that meritocracy is a problematic element in debates about social mobility and social justice are unsurprising.

I grew up in a relatively deprived region of Northern England, in a family unit that is probably best considered as a socio-economic outlier at the ‘well-off’ end of a very modest socio-economic spectrum. I am never entirely sure of my position in terms of socio-economic status classifications. But as Reay [3] reminds us, Melvyn Bragg describes himself as a class mongrel and I am quite content to be a class mongrel in the same vein. I went to university under a regime of no (or very low) student fee payments and learned just how unequal things were in the UK – and that in fact my relative social position in the hierarchy was less advantaged than I had thought.

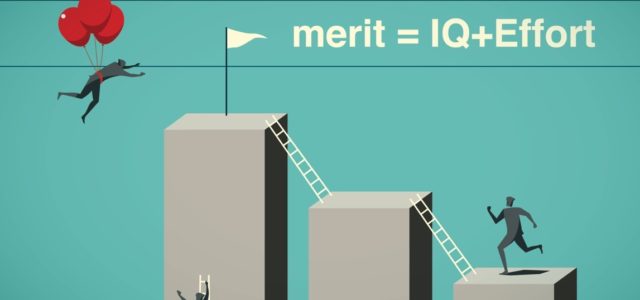

In retrospect, I see that alongside my new appreciation for my own social disadvantages I also benefited enormously from the advantage of attending university when students were not individually responsible for contributions to their tuition fees. This mix of advantage, disadvantage and transition underpins my ongoing ambivalence with respect to the concept of meritocracy. I can understand, intellectually, that the idea that effort + intellect = fair reward/advantage is problematic in all kinds of ways, not least in the way that Young initially suggested. At the same time, I am keenly aware that I benefitted from the way in which others have operationalised the concept in terms of access to higher education as a vehicle for social mobility. These effects have had a transformational impact on my ability to (eventually) obtain a relatively secure job, earning more money that I had ever expected, and a career in a profession that I love.

Taking a look at average incomes in the UK, whether it be the HMRC (50th centile income for 2015-16 is £23,200) or websites like Monster.co.uk (UK average salary for permanent staff as of 9.7.18 is £25,880), I now earn above twice the national average salary and have done for some time. It is possible to think, well if you were bright, if you worked hard at school and university, maybe there is some justice in that sort of earning position, it is a fair reward (Gallinat, Littler). But then again, you might look at the ‘global’ income rankings and realise that earning just over £60K puts someone like me in the top 0.11% of incomes globally for the Global Rich List. And even Monster.co.uk’s national average of £25,880 puts the average UK earner into the top 0.94% of earners globally, so perhaps there isn’t a great deal of social justice in there after all. I remain haunted, if you like, by the idea of taking more than my fair share. If I am taking at least twice the national average in the UK, whose share am I taking when I take that extra share? Toynbee and Walker [4] talk about the ‘camel caravan’, an analogy of the social problems created by inequality. Problems emerge not just when some get left too far behind, but also when others charge too far ahead. It prompts me to consider the legitimacy of wanting to charge ahead too quickly, instead of running with the group; our attempts to get too far ahead necessarily impact on others’ social experiences.

In my working life, as an academic and as a manager in higher education, I find myself surrounded by meritocratic reasoning, since (the idea or ideal of) ability-based reward is a fundamental feature of the university sector’s landscape. Getting into the ‘right’ university is often about getting the ‘right’ kind of A level results, while being at university is often about getting the ‘right’ kind of marks, to achieve the ‘right’ band of degree classification. Following university study, it’s about getting the ‘right’ kind of (graduate) work and earnings.

However, there are also challenges to some of these accepted hierarchies. For example, in learning and teaching, the concept of universal design is gaining traction. Universal design originated in architecture and was about removing physical barriers to people with physical disabilities so that they could use buildings fully, making the building a more inclusive experience for everyone. Applied to learning, this involves broadening the methods that are used to teach and assess [5] as a way of making learning experiences more inclusive, reducing the barriers that individuals face to learning and achievement. Such approaches to mitigating the impact of variation in individual levels of ability to widen access to good outcomes suggest that differential outcomes based on some aspects of variation in ability are no longer perceived to be fair.

There are also some interesting observations being made about research funding allocations. The process of allocating research funding in a way that is independent of direct political influence often depends on the idea that the ‘best’ proposal wins the funding on its own intellectual merits. But when research council funding application success rates are very low, the idea that a meritocratic system provides socially just outcomes begins to look more like a lottery than a meaningful competition (particularly when looking at the differences in levels of funding available for different sorts of research). The process for allocating research funding involves elements of meritocratic justice, but it also reinforces established privilege both within and between disciplinary areas. Some have argued, given the high standards of submissions overall, that a lottery system would actually be a fairer way of allocating scarce resource. Others have argued for a basic income model of research which goes to individual researchers but necessarily would be much smaller than a large project grant. Neither of these alternative approaches is problem-free, but I think itis interesting that we are talking about them as possibilities.

These instances represent attempts to address the uneven playing fields of access to resources in higher education but tend to leave the fundamental hierarchy of meritocratic outcomes unchallenged. Meritocratic logic is part of the landscape of our higher education, and it is likely to continue to hold a dominant position in our thinking. It can be a useful tool in making the social distinctions that underpin everyday functioning in our social worlds. But we might want to reflect further on how dominant a feature we wish it to be – can we make it part of the picture but not quite so dominant? As an academic in mid-career, I have to acknowledge my own privileged position within the higher education field, and my vested interests in wishing to continue earning a salary and pursue meaningful career opportunities. But I am also interested in thinking through my experiences of these everyday privileges, and how higher education could contribute to a broader framework of social justice: how we develop a sector in which early career academics and established academics can each thrive and be productive, how we recruit students from diverse backgrounds, how accessible the opportunities students experience as members of scholarly learning communities are, and what happens when they leave the university.

References:

[1] Ball, S. (2002) Class Strategies and The Education Market: The Middle Classes and Social Advantage, London: Routledge.

[2] McKee, M. and Stuckler, D. (2011) ‘The assault on universalism: how to destroy the welfare state’, BMJ 343:d7973.

[3] Reay, D. (2017) Miseducation: Inequality, Education and the Working Classes. Bristol: Policy Press.

[4] Toynbee, P. and Walker, D. 2009) Unjust Rewards: Ending the Greed that is Bankrupting Britain. London: Granta Publications.

[5] Burgstahler, S. E. (ed.) 2015) Universal Design in Higher Education: From Principles to Practice. 2nd ed., with a foreword by M.K. Young. Cambridge: Harvard Education Press.

Ruth Graham is a senior lecturer in sociology in the School of Geography, Politics and Sociology, and Dean of Undergraduate Studies in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Newcastle University, UK. Her research focuses on experiences of health care, encompassing collaborative projects with clinical practitioners on topics such as reproductive loss, and projects exploring contested issues in mental health.

Image: Wonderstuff, for this issue