Lisa Tilley

In recent years, far-right political figures have gained ground and power in various parts of the world, from India’s Modi, to Brazil’s Bolsonaro, to Trump in the US, as well as an array of European political figures who have built public profiles and constituencies around far-right agendas. These related political projects broadly seek to revive and build momentum around racist and exclusionary discourses, which in turn allow them to extend racist political action. As retrograde movements, they mine sedimented racisms in their respective social contexts and work to roll back the progressive gains of antiracist collectives achieved over the course of many decades.

In the British and wider European context recently, figures presenting themselves as liberal and centrist have made interventions in public discourses appealing for (further) anti-immigration concessions to appease the far-right. Hillary Clinton has been the latest high-profile figure to identify this particular hill as the one to die on, and a small but noisy clique of populist academics with books to sell in the UK have recently done the same. Their argument is essentially that the cause of far-right politics is quite simply the existence of what the far-right identify to be a problem – ‘ethnic diversity’, immigration etc. The solution is therefore to take these groups at their word and implement harsher, more exclusionary policies. ‘Give the far-right what they want and they’ll go away’ is the level of analysis they are pitching at here. Evidently, this wilfully ignores real historical accounts of fascist projects which intensify rather than dissipate as violent exclusions are realised. Far-right groups grow out of active political projects which thrive on powerful perceptions of exclusion and removal – there will always be another group to hate, more families to divide and deport, racialised women to incarcerate and abuse, and internal others to denigrate and persecute.

Such appeals to appease fascism do, at least, helpfully remind us of the articulations between the liberal centre and the far-right which operate within a broader ecology characterised by synergy more than discord.

With this in mind, I have been struck by how the concepts and categories of one discipline – political demography – have been notably prominent in recent populist academic interventions against ‘ethnic diversity’ as fuel for the far-right. A closer look at the genealogy of this discipline, from its original British colonial context to the present, is revealing. A key shift in the discipline of demography towards rigid quantitative methods and population ‘science’ occurred in Britain in the early twentieth century, not at the height of imperial confidence globally, but against the backdrop of growing momentum around decolonisation. White supremacy, of course, had long been the bone structure and ideational muscle of the empire which determined the material distribution of harm and protection, accumulation and dispossession along racial lines across global colonial territories and the metropole. Disturbances to this anatomy of empire in the form of the growing collective power of colonised peoples and an expanding collective anticolonial consciousness were clearly signalling the end for formal British control at this time. This deeply disturbed ‘activists’ for white power globally who directed their concerns towards the falling relative number of white bodies in the world compared with the growing number of those racialised as non-white. As the historian of empire Karl Ittmann explains:

“In the interwar years attention focussed on the expansion of non-white populations and the steep fall in British and white settler birth rates, which appeared to threaten the racial and ethnic balance of power in the empire. To counter this threat, activists called for higher white birth rates and new measures to manage the size and distribution of indigenous colonial populations” (1).

Colonial governments took seriously the racial power activists’ concerns and worked their techniques into technologies of imperial governance. Later, their ideas were finally solidified as demographic transition theory after 1945. This raises an interesting side question about whose activism comes to be crystallised into science in the first place, and of who comes to benefit from the legitimacy and power science bestows to their claims.

Colonial demography was evidently unable to prevent the empire from being brought down by the anticolonial actions of its subject peoples. However, it survived as a ‘science’ in the old metropole (and beyond) in coded and somewhat sanitised versions and diversified its concerns and areas of study. Importantly though, it was never divested of its foundational concern for the racial balance of power across that all-too-material colour line between whites and non-whites. As such, political demographers can still present ‘scientific’ arguments about ‘overpopulation’ in coded racialised geographical areas and dwell on dwindling white populations at the urban or national scale in the global North without critical reflection on the roots and implications of such priorities.

To be motivated explicitly by white power has been rightly made unacceptable in recent decades, considering how inextricable this is from the violence of colonial projects, the KKK, and other far-right groups. So, how can academics drawing on crude (colonial) demography sustain arguments around the ills of ‘overpopulation’ among non-white peoples in relation to the ‘problem’ of falling white birth rates and ageing white populations when one obvious solution to these pressures is migration? In such analyses, white anxiety over the racial balance of power has been displaced to a convenient external regulatory actor – the ever-looming and ever-violent far-right. The far-right, then, becomes a vital disciplinary device in a range of ‘respectable’ anti-migration analyses from those positioning themselves in the ‘centre’ of ideological debates, as much as those on the right and indeed the left. In other words, the centre needs the threat of the far-right to regulate the boundaries of what is considered politically possible because overt expressions of concern over perceived diminishing white power have largely been made unacceptable.

Thanks to anticolonial and antiracist struggles and as a result of the genocidal conclusion of the Nazi project, we do have collective moral codes which have made explicit advocacy of eugenics, colonialism, and other race-based projects associated with violence and exclusion unacceptable in many areas of public discourse, unless these are heavily coded. However, it is no coincidence that some academics and public figures are pushing against these boundaries in the present moment of far-right resurgence. Toby Young and his academic friends held a series of secret eugenics events at UCL in recent years and there have been explicit calls for the still-warm corpses of eugenics and colonialism to be re-animated in previously respected scholarly journals. This loose movement to resurrect ideas associated with degrees of racial violence and genocide is aided by campaigns around unbounded free speech (focused on securing access to platforms for far-right speakers) and further active projects to construct a monolithic object of hate out of the diverse left (see attacks on a fabricated lack of ‘viewpoint diversity’ and denigration of social justice ‘ideology’ etc also propagated by Toby Young and friends).

However, recognising the present dangers of the far-right threat and articulated efforts by academics to bring back eugenics and colonial science in decoded form is not to suggest that the liberal present is a violence-free neutral state to be preserved. Beyond thousands of annual European border deaths and the scandal of Windrush, around 40,000 people are deported from the UK each year, while 25,000 are incarcerated in Britain’s hellish removal centres, betraying a system which Gracie Mae Bradley notes is characterised by ‘a logic of dehumanisation.’ For all the difference between ‘normal’ liberal eras and hard right rule (cf deportations under Obama vs those under Trump) for those directly in the fire of racialised state practices the difference in experience might be reduced to the question of which sauce it is better to be cooked in, as the old Eduardo Galeano story goes (2). The qualitative difference under a leader like Trump, of course, is the firm re-racialisation of popular discourse and an expansion of the boundaries of what is possible in terms of racist violence.

What is absolutely clear is that populist academics, with their outdated colonial commitments to the racial balance of power, are utterly wrong – both morally and empirically – and history will judge them harshly as such. In the present we need politics and policies informed by real histories, accurate political economy, and collective moral sense. Vital truths to begin with include, but are not limited to the following: Firstly, British and other European empires forcibly included global South peoples against their will over the course of the colonial centuries. By 1925 Britain as an imperial state included 450 million people, encompassing one quarter of the world’s population. As such, “we did not come to Britain, Britain came to us” and “we did not cross the border, the border crossed us” are empirical statements, not meaningless platitudes. Former colonial subjects and their descendants have a moral right to dignified lives in the metropole as much as they have a moral right to dignified lives in their homelands. Secondly, imbalanced global political economic structures instituted during the formal colonial centuries remain in place and continue to produce poverty in the global South, much of which remains trapped in low-value extraction and continues to be drained by the global financial system. Thirdly, aside from China as the world’s major producer, former colonial powers and their old white liberal settler colonies (Europe, the US, Australia etc) continue to pollute and consume the most, accounting for most of the world’s harmful greenhouse emissions. Climate change resulting from these emissions will mean that more and more people will have to leave home in search of viable lives across borders as sea levels rise and weather patterns become increasingly destructive.

In sum, it is vital that we break the power of fabricated moral panics around immigration and ‘ethnic diversity’ – these maintain the far-right ecology which the media, pundits and populist academics all do their bit to cultivate. Academics (not only demographers and not all demographers) are often working within disciplinary parameters which were determined for the colonial purpose of expanding and maintaining white power. Without determined dismantling of these foundational goals, their disciplines can easily be put to use in the service of white power in the present.

The real violence of deadly regimes of exclusion and far-right action – quantifiable as border deaths, deportations, and violence in society – will only get worse if liberals and populist academics continue to rationalise and operationalise the agenda of the far-right and if their voices remain dominant. In the meantime, a distinct ecology of knowledge and justice is flourishing – one based on real histories and viable futures for all, and which demands nothing less than the wholesale dismantling of far-right political projects in the present.

References

1. Ittmann, K. (2013) A Problem of Great Importance: Population, Race, and Power in the British Empire, 1918—1973.

2. Galeano tells the story of a chef who gathers together all of his poultry to ask them an important question. His query for the birds is: “in which sauce would you like to be eaten?” One of the birds said, “but we do not want to be eaten in any way at all.” To which the chef replied, “but this is not the question!”

Lisa Tilley is a Lecturer in Politics and Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at Birkbeck University of London. She is also co-convenor of the Colonial, Postcolonial, Decolonial (CPD) Working Group of BISA.

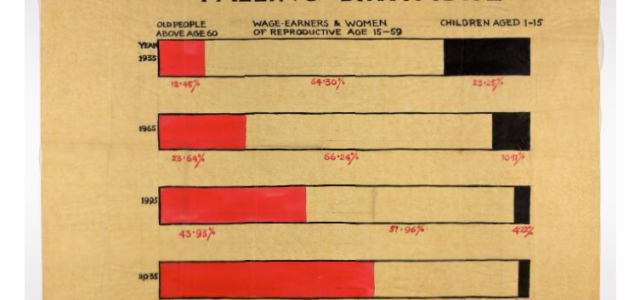

IMAGE CREDIT: Wellcome Library shared under Creative Commons Licence CC-BY-4.0