Alan Warde, Jennifer Whillans and Jessica Paddock

Culture change is a much vaunted contemporary panacea for social ills. It is invoked to remedy institutional racism, political corruption, sexual predation within the entertainment industry, bad corporate environmental practice, and much else – including gender relations. Getting men into kitchens is a case in point.

One of us owns a tea towel which says, ‘Men are like fine wine. They all start out as grapes. It’s our job to tread on them and keep them in the dark until they mature into something you would love to have dinner with‘. Fair diagnosis; specious projection. It depends how long maturation takes. Wine, reassuringly, requires many fewer years than three score and ten. What is the time frame for the expeditious transformation of men’s behaviour? And surely it is better if they also cook the dinner!

British studies of families, households and communities demonstrate that in the aftermath of the Second World War cooking at home was almost exclusively a role for women. After ‘the servant crisis’ of 1920s and 1930s food preparation fell to women of all classes beyond the elite whether or not they had skill, aptitude, temperament or patience for the activity. In the third quarter of the 20th century a man might occasionally fry breakfast or singe meat on a barbecue, but in the main they received meals, sometimes gratefully and graciously, sometimes critically and bitterly, but mostly, we suspect, in a taken-for-granted and habituated way.

The status quo came under increasingly intense scrutiny in the 1960s. Research in the later 20th century showed increasing homage being paid to the idea of sharing domestic tasks within couples, but not a great deal of change in behaviour (Warde and Martens 2000). It was noted that men sometimes carried out domestic tasks popularly stereotyped as feminine, sometimes because there was no alternative, sometimes because they quite liked doing them (ironing and cleaning lavatories not being included in that category), but also increasingly because they were persuaded that they ought to. An ideology of companionate marriage, as sociologists described it, was becoming dominant.

It is much trumpeted that men do more in the kitchen now than in the mid-20th century. Men are more engaged in food preparation at home. In 2015, 64 per cent of men reported being either ‘quite interested’ or ‘very interested’ in everyday cooking, only 10 per cent fewer than women. More significantly, in 1995 a man prepared the last meal eaten at home on 33 per cent of occasions, a proportion rising to 37 per cent by 2015.

Why might men cook more than before? Part of the answer is change in household composition; while heterosexual couple households still predominate more people live alone, in gay couple households and in multi-occupancy arrangements. There are also well documented practical reasons. Many households would be seriously deprived of opportunities to eat home prepared meals if men never cooked them. Hungry children in dual-earner households, where disruptive hours of employment mean that men cannot feasibly always avoid putting a meal together (see Brannen et al, 2013). But also maybe cultural change has normalised greater male participation.

Chef has become glamorous occupation with increasing status; it is no longer embarrassing for middle class parents to admit that a son is training to be a chef. According to Neuman and colleagues (2017), in Sweden a principal element of the contemporary idealised form of masculinity, one which is softer and more family-centred, expects a capacity and readiness to prepare family meals. Not to do so would be a source for dishonour among young Swedish men.

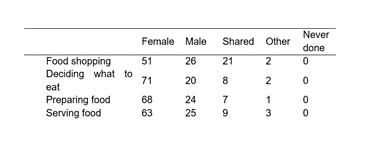

Has there been a change of culture in Britain? We have conducted a study using surveys and interviews which asked identical questions about household work around food to a similar sample of people in three English cities in 1995 and 2015. Media might give the impression of radical change but the true story is less dramatic. Men are more involved in preparing meals at home than 20 years ago even in heterosexual couple households, the sites most revealing of change in the gender division of labour. Household meals require several different types of labour and Table 1 shows that women are much more likely to carry out all tasks. For essential tasks, on the majority of last occasions undertaken, women had been responsible, including deciding what to eat (71% women), preparing food (68%), serving food (63%) and food shopping (51%). Gender differences in subsidiary food tasks (setting and clearing the table and washing up) were less pronounced but still more of women’s labour was involved.

Table 1 Who carried out specific tasks last time?: (heterosexual couples, aged 18-65, 2015: row percentages)

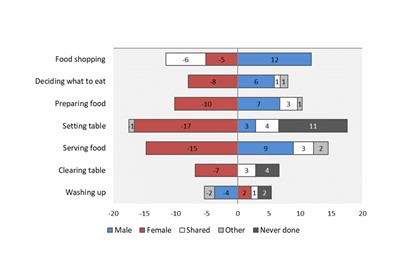

Comparison with 20 years earlier nevertheless suggests some convergence in the roles of men and women. Figure 1 shows that women were less likely to have done each task ‘last time’, with the exception of washing up, suggesting men’s increasing responsibility for both essential and subsidiary tasks. The most notable increases were in men’s responsibility for essential tasks, with men now more likely to decide what to eat (6%), to prepare food (7%), to serve food (9%) and – the largest increase – do the food shopping (12%). One interesting incidental feature of Figure 1 is the increasing proportion of households who never do certain subsidiary tasks, most notably setting the table. As one interviewee said, ‘Laying the table, we wouldn’t… it’s more like, when you carry the plates in, there’s a knife and fork, rather than formally laying the table.’ But despite these apparently impressive percentage changes, women continue to have a highly disproportionate share.

Comparison with 20 years earlier nevertheless suggests some convergence in the roles of men and women. Figure 1 shows that women were less likely to have done each task ‘last time’, with the exception of washing up, suggesting men’s increasing responsibility for both essential and subsidiary tasks. The most notable increases were in men’s responsibility for essential tasks, with men now more likely to decide what to eat (6%), to prepare food (7%), to serve food (9%) and – the largest increase – do the food shopping (12%). One interesting incidental feature of Figure 1 is the increasing proportion of households who never do certain subsidiary tasks, most notably setting the table. As one interviewee said, ‘Laying the table, we wouldn’t… it’s more like, when you carry the plates in, there’s a knife and fork, rather than formally laying the table.’ But despite these apparently impressive percentage changes, women continue to have a highly disproportionate share.

Figure 1 Percentage change in who carried out the tasks last time (1995-2015)

The distribution of food tasks within couples is negotiated as part of wider household organisation of labour, leaving room for differing judgments of fairness. Equal shares and fair shares are not synonymous. We asked ‘Overall do you think that you do your fair share, or more, or less, of these tasks?’ Men’s and women’s responses show some re-distribution in perceptions of equity. Around a quarter of male partners, in both years, say that they do less than their fair share of food work. In both years, men’s most common response was that they do their fair share, but by 2015 18 per cent of men claimed to do more than a fair share (an increase of 7%).The biggest change in women’s responses is an 11 per cent decline in reporting doing more than their fair share of food work (from 51 % to 40%), with the most common response (54%) being ‘I do my fair share’. Nevertheless, in 2015, two women in five still say they do more than is fair, a proportion twice that of men. Interestingly, there is no relationship between how much work a man does and his judgment of whether that is fair, while there is a clear relationship between how much a man does and his female partner’s estimation of fairness.

Thus our statistical evidence confirms the findings of other studies (eg Sullivan, 2000; OECD). Men do less than women. However, they do contribute a greater proportion than before. Might we then be optimistic that steady and small changes will accumulate and accelerate so that women and men feel equally satisfied with their allocation? Interviews with younger men suggest some generational effect, in-depth interviews revealing greater mutual engagement and awareness of issues of parity. They say that they enjoy cooking; 63 per cent of men (c.f. 79% of women) said they were quite or very interested in cooking for special occasions. Since men who like cooking actually cook more, more equitable arrangements might evolve.

A pessimist, however, might anticipate a long wait. The percentage increase in men’s work may be unduly flattering because fewer tasks are completed more quickly rather than a stirring of enthusiasm for housework. Greater engagement of younger men may be a function of the early years of a partnership and the practicalities of managing child care. It remains as difficult as ever for younger women to unilaterally abdicate primary responsibility for food preparation, even when they dislike it.

On balance, in 2015 arrangements for domestic food preparation are less rigid and scarcely anyone articulates the traditional gender role ideology common in mid-20th century. Practical adaptation to a changing social environment is probably a large part of the story. Some tasks are abbreviated, others like setting the table eliminated. Cooking a meal is simplified. Time spent cooking has fallen steadily since the 1970s. Commercial alternatives to the domestic meal are more readily accessible. More single people and more people living alone dilute gendered divisions.

Whichever projection proves best all might agree that the pace of cultural change is not conducive to rapid improvement. If food preparation is gradually sloughing off some its heavily gendered coding it is happening at a painfully slow rate. Several decades of promotion of companionate marriage and the elevation of the status of the activity of cooking have only marginally altered the balance within couples. Do not therefore expect too much to happen when abusers of authority shelter behind promises of culture change.

References:

Brannen, J., O’Connell, R. and Mooney, A. (2013) ‘Families, meals and synchronicity: eating together in British dual earner families’, Community, Work & Family, 16: 417-434.

Neuman, N., Gottzén, L., & Fjellström, C. (2017). Narratives of progress: cooking and gender equality among Swedish men. Journal of Gender Studies, 26, 151-163.

Sullivan, O. (2000) ‘The division of domestic labour: twenty years of change?’ Sociology, 34(3) 437-456.

Alan Warde is Professor of Sociology in the School of Social Sciences and Professorial Fellow of the Sustainable Consumption Institute at the University of Manchester. He is currently conducting a study of eating out in Britain, with Jessica Paddock and Jennifer Whillans. His most recent book is Consumption: a sociological analysis, published by Palgrave in 2017. Jennifer Whillans is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow, based at the Sustainable Consumption Institute, University of Manchester. Her current research project is (De)synchronisation of people and practices in working households: The relationship between the temporal organisation of employment and eating in the UK. Jessica Paddock is a lecturer in Sociology at the University of Bristol. Her research is concerned with how a sociological understanding of everyday eating practices can inform transitions towards more sustainable societies.