Mark Johnson and Jamie Woodcock

Twitch is an online platform that enables anyone with a mid-range computer and a reasonably fast broadband internet connection to broadcast themselves playing video games to a potentially massive audience. In 2015 around two million people regularly broadcasted (“streamed”) their gameplay live on Twitch, and many times that number tuned in; this has reached the point where thousands of broadcasters are able to make their full-time income simply from the money given to them, voluntarily and entirely optionally, by their viewers. On the most basic streams this means simply recording, uploading, and then broadcasting (with a delay of only a few seconds) the game itself and nothing else, but more advanced streamers include webcams of the player(s), alongside notifications when a viewer has donated, various sounds, music, graphical overlays and artistic elements, and links to where the broadcaster can be found on other social media platforms. Other digital economy actors with interests in content creation and management have not been slow to notice this meteoric growth and the newfound overlap of Twitch broadcasters with other platforms and websites; although only several years old, Twitch was recently purchased by Amazon for just under $1bn, and continues to become an increasingly strong competitor to the dominance of YouTube in the online video ecosystem.

A central part of Twitch, and the element we focus on here, is the presence of “Twitch chat”. This is a live chat window that exists alongside the video stream. This enables viewers (who have made an account on Twitch) to post messages to other viewers, and to the broadcaster – the streamer then (generally) works hard to respond to these comments and questions. Under ideal conditions (more on this later) this results in an almost-live dialogue between the broadcaster and their viewers, sharply shrinking the gap between media producers and consumers, and between digital celebrities and those who follow their work. Twitch chat can also be seen as a new form of social media, enabling interactions between one viewer and another as well as interactions with the broadcaster, fostering new fleeting social worlds that arise and vanish with each broadcast, but also show signs of continuity, with particular communities becoming embedded with particular streamers.

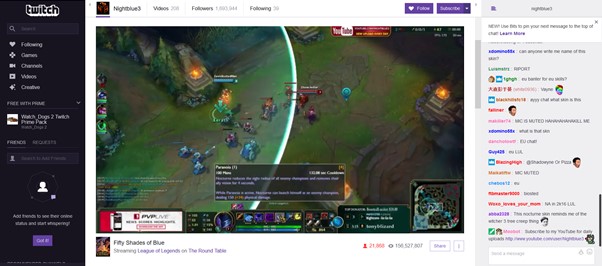

Image 1: Twitch Broadcast

The Twitch web page is divided into three vertical sections that can be seen in the image above: on the left, a number of options related to the platform, primarily for navigating the site; in the middle, the live stream including both footage of the streamer and the broadcast of the game (in most cases) whilst above and below this are additional details about the streamer; and on the right is the chat box. The chat function allows users to type text or “emoticons” or “emotes” – little symbols or pictures designed to convey a particular emotion or concept – into a vertically flowing discussion space. New messages are added to the bottom, and move up once others are added. On smaller streams this allows viewers to communicate with each other and the streamer, while on larger streams the volume of messages can make this a more complex task. The largest streams can accrue five-figures or even six-figures of viewers, at which point – unless action is taken by those in charge of the stream – any kind of meaningful conversation becomes impossible, but viewers nevertheless continue to post messages. Indeed, on particularly fast-moving chats, this becomes something of a joke, with viewers posting messages that “will never be seen” due to the speed of its movement, and making (generally fake) confessions about themselves in the process.

The Twitch chat allows basic interaction of text messages, but has also grown to involve special emotes that are designed for the platform. One of the most famous is ‘Kappa’, the face of a former employee of Justin.tv – the website that became Twitch – and is used to signify either sarcasm or trolling. The ‘BibleThump’ emote indicates sadness, reusing an image from the game The Binding of Isaac. Another emote is duDudu, an icon that is meant to represent the song Sandstorm by Darude, which has evolved into something of a longstanding meme on the platform. In a similar vein, the ‘ResidentSleeper’ emote features the face of a streamer called Oddler, who fell asleep during a live 72-hour Resident Evil marathon and remained on camera, which soon became a famous event in the early days of the website. These are supplemented by more general internet memes and online humour, but also highlight the distinctive patterns of Twitch chat that have emerged on the platform – particularly examples like ‘Kappa’ that feature staff members. The community has created and latched onto a set of internally-facing memes with little relevance outside of the Twitch community, resulting in a massive set of in-jokes and brief fashions and fads that are quite opaque to the outside, but a fundamental part of its rapid growth and the particular kinds of social interactions that take place upon the platform.

Image 2: The ‘Kappa’ emoticon

Alongside conversations and emoticons, Twitch chat has evolved in a number of new directions, adding new abilities and flexibility to what appears at first glance to simply be a window of text, and boosting the social complexity of the site. For example, are numerous ways to mark out certain viewers as being “superior” within the context of a particular channel to others, and these methods have added a range of behaviours to the site and come to shape interpersonal interactions in Twitch chat in particular ways. One of these is the ability to “subscribe” – doing so results in viewers giving a small amount of money to the streamer and to Twitch each month, in exchange for which they get a special icon next to their name, and access to a range of special emoticons. Subscribers and normal viewers – often referred to by the derogatory title “plebs” – have access to different abilities, and normal viewers can sometimes be barred from chatting under particular circumstances, creating an inevitable social divide. Equally, in recent months the ability has been added for streamers to vary subscription icons based on how long the subscriber has been present for, resulting in different tiers of subscriptions instead of a binary subscriber/non-subscriber divide; this is then a strong encouragement for viewers to remain subscribed in order to reach the best icon for a given stream after many months, and represents a gamification of the subscription process itself. In turn, even subscribers themselves are now ranked, given social status for those who have been subscribed longer, rather than simply those who are subscribed per se.

Twitch chat and the social relations between viewer and streamer are made more complex on channels that allow “cheering”. Cheering is a new system added to Twitch in the past year. In order to “cheer” viewers purchase digital currency known as “bits”, and then during the broadcast they type in a command of the sort “cheer[x]” which then “cheers” for the streamer (“or “cheer[x][playername]” for a competitive gaming competition with multiple players). It then directly transfers money – a microtransaction of 1¢ per bit – to the player themselves. Streamers who receive more cheers from viewers sat at home therefore receive more income (from this source) than those who are rarely cheered. Cheering, a phenomenon we are currently examining more fully, therefore raises intriguing questions about what causes spectators to cheer – doing well, or even doing badly, or performing particular actions – and whether gamers will be able to “game” the system in order to maximize how much players cheer for them. It also brings viewers closer to the players and makes them more engaged and entangled with the gameplay, further developing the sense of community already inculcated by Twitch chat even in its simplest form. This is particularly noticeable in competitive gaming broadcasts, where the supporters of two players compete to out-cheer the supporters of the other. Whilst on one level a spectacle obviously reminiscent of traditional sports, the key difference is that cheering leads directly to supporting a specific individual, and in this context especially shows how links between viewers are strengthened by cheering, and viewers come to feel a more direct connection with the broadcaster than with other kinds of digital celebrity.

Image 3: Bit emotes

The importance of inculcating such a sense of closeness has been seized upon by enterprising broadcasters, with the naming of one’s communities of viewers becoming a central part of developing success on Twitch. Streamers have taken to producing names and titles for those who view their channel: one collection of viewers/chatters might be “the Wolfpack”; another might be “the Core”; another might be “the Army”; and so on and so forth. Such terms are designed to elicit a feeling of collective identity between all viewers of a channel and the broadcaster, and in turn to encourage them towards staying on the channel, subscribing to the channel, maintaining subscriptions, and so forth. Such a practice is similar to the creation of groups on Facebook, or the use of hashtags on Twitter, but retains a very distinct set of dynamics for how it affects social behaviour on the platform; this is another dimension of Twitch chat that merits further exploration in the future.

Twitch chat is one of the least examined forms of contemporary social media in the world. It is difficult to unpick all of its social dimensions here, but in this piece we have attempted to highlight some of the core components of how people behave: their relationship to the broadcaster and the creation of celebrity intimacy; how emoticons and in-jokes serve to create a sense of overall Twitch community that can seem very peculiar to outsiders, but gives legitimacy to the actions of those inside; the different “tiers” and levels that those within Twitch chat possess and how this can structure who is allowed to speak, or whose comments are respected, in particular contexts; how cheering is used to connect viewers even more closely to the games being played and let viewers influence, in a small way, the on-screen action; and how community names and identities are created in order to further build the perception of intimacy and connection between viewers and broadcasters. The rapid growth of Twitch shows that such chat systems are important for our consideration of digital social futures and the changing methods people use to communicate, and with our ongoing research project into Twitch we seek to unpick many of these dynamics in detail and consider their impacts upon the social lives of internet users.

Mark Johnson is a postdoctoral fellow in game studies in the Digital Creativity Hub at the University of York (UK), an independent game developer and co-host of the Roguelike Radio podcast, and an ex-professional gamer currently pursuing a number of arcade gaming world records. He’s also working on his first monograph, The Unpredictability of Gameplay, to be published by Bloomsbury Academic.

Jamie Woodcock’s current research focuses on the digital economy, the transformation of work, and eSports. He has previously worked as a postdoc on a research project about video games, as well as another investigating the crowdsourcing of citizen science. Jamie completed his PhD in Sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London and has held positions at Goldsmiths, the University of Leeds, the University of Manchester, Queen Mary, NYU London, and Cass Business Sch