Peter Jackson

In March 2016, Tesco faced criticism for labelling new food products with the names of farms that proved to be entirely fictional. ‘Boswell Farm’ beefsteaks and ‘Woodside Farm’ sausages joined a long list of other food products whose naming is more of a gesture towards their generalised provenance than an indication of their actual geographical origins. While The Soil Association condemned the use of such ‘brands of convenience’, calling for honesty and authenticity not deceptive veneers, not everyone seemed equally concerned, judging by the comments that followed the online publication of the story in The Guardian (22 March 2016). Among these rather jaundiced observers, one commentator asked whether people really believe that Goodfellas’ pizza is actually made by Italian-American gangsters or whether Mr Kipling really makes all those ‘exceedingly good cakes’. Others made sarcastic suggestions for naming Tesco’s future brands including Animal Farm (after George Orwell’s dystopian novel) and Broadwater Farm (the estate in Tottenham where riots broke out in the 1980s). What do such incidents tell us about contemporary food marketing? Why are supermarkets so keen to use idyllic-sounding names in the branding of their produce? And should consumers be outraged at such apparent deception or blasé about the practice, accepting that all marketing claims are half-truths at best or outright fabrications at worst?

In our media-saturated world, food is increasingly ‘sold with a story’, using branding to provide positive messages about a product that go far beyond its actual material properties. Often, these stories use geographical imagery or specific place-names. My personal favourite, from several years ago, was the advertisement for Alta Rica instant coffee which claimed to come ‘from the heart of Colombia and the soul of Nescafe’. But there are many other examples that make serious or playful reference to place in an attempt to give even the most manufactured and highly processed products a positive aura. Provenance claims have increased significance in a period of globalization, where many products are imported from far away and where consumers are increasingly divorced from food’s actual site of production.

Nor is Tesco alone in using these marketing practices. When the naming of ‘Oakham’ chicken was called into question, for example, a Marks & Spencer poultry buyer argued that the name had been chosen because it evoked ‘countryside imagery and nice places’:

It’s more about an image than it is a place…. I suppose it does sound British, there is a Britishness to it, because it sounds like – I don’t know where it is – but it sounds like it’s a place in Britain, you know, and there’s that kind of provenance feel, a bit like Aberdeen Angus, because that’s effectively what we were looking for … the Aberdeen Angus of the poultry world (Catherine Lee, interviewed by Polly Russell, 30 January 2004, for The British Library National Life Stories, C821/121/04).

Unlike ‘Oakham’, however, which is a real place in the English midlands with no direct connection to the production of Oakham chicken, Aberdeen Angus refers to a specific provenance (Aberdeenshire in Scotland) and to a specific breed of cattle. Later, when Marks & Spencer were challenged about the origins of their ‘Lochmuir’ salmon — a name chosen by a panel of consumers because ‘it had the most Scottish resonance’ — a company representative responded unapologetically: ‘We have taken the same principles of Oakham chicken and applied them to fish’ (‘M&S Lochmuir salmon… only Lochmuir doesn’t exist’, The Scotsman, 19 August 2006).

Transparency became a big issue for the food industry in 2013 during the horsemeat scandal, when several British supermarkets were found to be selling adulterated meat, having failed to impose sufficient control over their supply chains, creating the opportunity for widespread food fraud. While consumer confidence dipped in the immediate aftermath of the incident, sales of frozen beef-burgers and other processed meat products quickly rebounded, suggesting that consumers have short memories or that our purchasing habits are so deeply embedded that they are hard to shift beyond short-term perturbations. (There is further discussion of these ideas in my book Anxious Appetites: food and consumer culture, 2015.)

Food safety authorities such as the Food Standards Agency have sought to regulate these practices in pursuit of greater consistency and transparency in food labelling. In one telling example, the FSA tried to establish some agreed criteria for the use of words like fresh, pure and natural, updating their guidance on several subsequent occasions.(1) Accepting that there was no legal obligation on food businesses to follow their guidance, they cited consumer research, public consultations and correspondence on the topic to argue that consumers were concerned about the way some labelling terms had become unclear. Their original list included the words fresh, natural, pure, traditional, original, authentic, homemade and farmhouse. This was later expanded to include real, hand-made, selected, quality, premium, finest, best, seasonal and wild. Acknowledging that the description ‘fresh’ can be helpful to consumers ‘where it differentiates produce that is sold within a short time after production or harvesting’, the FSA warned that: modern distribution and storage methods can significantly increase the time period before there is loss of quality for a product, and it has become increasingly difficult to decide when the term ‘fresh’ is being used legitimately (FSA 2008: para 26). Technological innovations have added further complications and the Agency advised that ‘a food that has been vacuum packed to retain its freshness should not be described as “freshly packed”’ (ibid. para 32). The Agency advised that it was acceptable to describe fish that has been kept chilled on ice but not stored deep frozen as ‘fresh’ (para 38) but that fruit juice prepared from concentrate should not be described as ‘freshly squeezed’ (para 42). Tracing these verbal complexities is one way in which the nature of contemporary food systems can be examined.

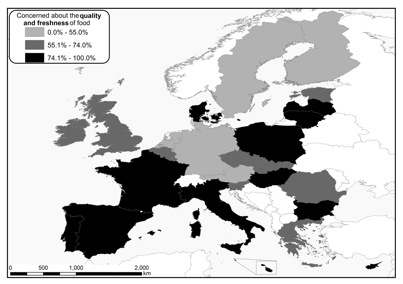

We have recently begun a new project on the ‘enactment’ of freshness in the UK and Portuguese agri-food systems, focusing on poultry, fish, and fruit and vegetables, where we are building on Susanne Freidberg’s pioneering work, Fresh: a perishable history (2009).(2) Acknowledging that ‘fresh’ foods often reach consumers after a complex process of transportation and refrigeration, Freidberg coined the term ‘industrial freshness’ to highlight the paradox of ‘fresh’ foods that are anything but ‘natural’ in terms of their mode of production. Survey evidence suggests that consumers are concerned about these issues, with 68% of respondents to a Eurobarometer questionnaire reporting themselves concerned about the quality and freshness of food. Interestingly, though, there are considerable variations in levels of concern across Europe, ranging from 37% in the Netherlands to 94% in Lithuania (see Figure 1). Our comparative research on the UK and Portugal is designed to shed further light on these differences.

Figure 1: European concerns about the quality and freshness of food

Special Eurobarometer 354: Food-related risks (2010).

It is also worth reflecting on the historical specificity of these concerns. The Marks & Spencer archive at Leeds University contains a wealth of material on the company’s marketing campaigns and consumer messages. Among them, the following leaflet from 1995 is a particularly striking example (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Marks & Spencer promotional leaflet (1995)

The leaflet shows a range of fresh vegetables, superimposed on a series of maps. The inside cover includes a compass to reinforce the idea that consumers are being invited to go on a ‘voyage of discovery’. Clearly dating from a time before ‘food miles’ had become a major environmental issue, the leaflet argued that:

Fresh vegetables from faraway places are no longer a luxury. Fresh, healthy and convenient, the best selection in produce and prepared recipe dishes is now available all year round at Marks and Spencer.

The leaflet continued to describe how the company’s suppliers ‘travel the world to bring you the very best produce … full of goodness and flavour … ready to use with minimum fuss and waste’. The leaflet boasts about how Marks & Spencer was ‘revolutionizing production and harvesting techniques to offer vegetables that are consistent in size, texture and flavour’. Current concerns about the acceptability of misshapen fruit and vegetables were not yet on the agenda, though the connection between diet and health was clearly already an issue:

From harvest to basket we strive to ensure our vegetables reach you in prime condition. Fresh St Michael vegetables not only taste delicious, they are also rich in essential vitamins and minerals necessary for a healthy diet… All M&S recipe dishes are made with fresh vegetables and – great news for slimmers – most are less than 300 calories per portion.

While marketing messages can be rejected as deliberately misleading or inherently partial accounts, they can also be treated as evidence of society’s changing attitudes and food-related anxieties. Words like ‘fresh’ and ‘natural’ convey a host of meanings that go far beyond the material properties of particular foodstuffs. Notions of provenance contain a wealth of cultural connotations beyond specific geographical origins. Current controversies about food labelling are rooted in historical concerns about social and technological change where our modern highly industrialised agri-food systems have led to increasing distance between producers and consumers – a gap which contemporary marketing practices now seek to exploit. Understanding how these systems and practices work might give us further insight into the uneven distribution of power on which they depend.

Notes:

(1) The original guidance was published in 2001. The July 2008 update is available here.

(2) Funded by ESRC, the project is led by Peter Jackson in Sheffield with colleagues in Manchester and Lisbon.

Peter Jackson is Professor of Human Geography at the University of Sheffield. He is a co-author of Food Words (2013), co-editor of The Handbook of Food Research (2013) and author of Anxious Appetites (2015, all published by Bloomsbury). Besides his academic work, he also serves as Chair of the Food Standards Agency’s Social Science Research Committee. See also: ERA-Net convenience food project and the A-Level Geography subject overview on food production