Hilary Rose and Steven Rose

In 2008, on the very cusp of the banking crash, the Labour government published a Foresight Report entitled Mental Capital and wellbeing: making the most of ourselves in the 21st century. The Report’s headline assertion is unequivocal: ‘Countries must learn how to capitalise on their citizens’ cognitive resources if they are to prosper, both economically and socially. Early intervention will be the key.’ Unsurprisingly, its central concept of Mental Capital is close kin to the Human Capital theory of the Chicago school of economics and emphasises the non-material dimensions for economic growth. The theory has long influenced education policies in the OECD countries; the innovation in Foresight and for UK policy is the turn to neuroscience as providing the scientific basis for early intervention.

Mental Capital is both a property of the individual and of the nation. For Foresight, ‘the idea of capital naturally (sic) sparks association with ideas of financial capital and it is both challenging and natural (sic) to think of the mind in this way’. Who, its rhetoric more than hints, can go against ‘nature’? Look after the accumulation of mental capital from babyhood onwards of disadvantaged children and they and the national mental capital and economic growth will flourish.

Early Intervention

In 2008, the same year as Foresight, Labour MP Graham Allen and Tory MP Iain Duncan Smith published a joint report advocating neuroscience based early intervention for disadvantaged children. Two years later, David Cameron, the incoming Prime Minister, set out the case for a counter-revolution in social policy. Enhancing the quality of parenting, he claimed, was key to lifting children out of poverty, though it wasn’t until 2015 that the new Conservative government was free to develop their programme of replacing welfare by the moral policing of the poor so as to control their ‘entrenched worklessness, family breakdown, problem debt, and drug and alcohol dependency.’ The Charity Organisation Society couldn’t have said it better. Reneging on their own Child Poverty Act and redefining the concept of poverty were essential next steps. No longer was poverty to be measured by relative income, but by relative lack of mental capital such as low educational achievement.

The Allen Reports

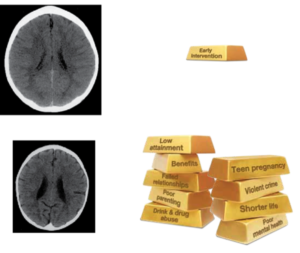

By 2011, with Duncan Smith Coalition Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, Allen had produced two more reports (here and here). Both front covers feature MRI images of two brains, the one described as that of a normal three year old, the other, much smaller, labelled ‘extreme neglect.’

Both are brilliant propaganda, exploiting the power of brain images to convince. The reports claim that the first three years of life permanently shape a child’s cognitive, social and emotional future, and that proper parenting over these years is crucial. Get things wrong, and the child’s brain will not grow properly, and negative consequences will follow: get them right, and huge benefits flow. To secure these potential gains the State should intervene in the interests of the child’s mental capital and hence the growth of the economy. The cover of the second report highlights these claims by placing alongside the MRI images a pile of gold bars variously labelled ‘low attainment, benefits, failed relationships, poor parenting, drink and drug abuse, teen pregnancy, violent crime and shorter life’ – the heavy costs to the tax-payer of failure to intervene.

Early Intervention, implemented by social workers and health visitors trained in neuroscience methods that will enhance cognitive and emotional development, fits neatly within this changed concept of poverty. By his second report, Allen waxes euphoric; there will be massive savings to the public sector finances, fewer prisons will be needed, and the structural deficit could even be eliminated. But the programmes will need resources. And here, in a move guaranteed to appeal to a government committed to privatisation and the small state, Allen proposes that his programmes be funded either through the voluntary sector, or through specific outcome-based contracts to private providers. Small wonder that his reports were commended by organisations ranging from accountants PriceWaterhouseCoopers through Portland Capital and Goldman Sachs to the Metropolitan Police.

Allen’s reports each ended with the proposal to establish an Early Intervention Foundation, and indeed, by 2013 the Foundation had been recognised as an independent charity with him as its Chair. A quick look at a few of its most recent publications suggests that the public sector, ESRC, Home Office, DES and the Cabinet Office, along with one charity, is funding the research stage. So it looks as if the self-financing early intervention programme has yet to start.

The appeal to neuroscience

For Allen, the first three years are ‘far and away the greatest period of growth in the human brain…synapses in a baby’s brain grow 20-fold from having some10 trillion at birth to 200 trillion at age 3.’ It is the period over which a baby attaches to its mother, and the secure environment that this provides, is the substrate for full cognitive and emotional development. His reports were soon followed by others, notably The 1001 Critical Days, sponsored by the Wave Trust and the NSPCC and endorsed by a cross-party group of MPs. 1001s research base improves on Allen’s time frame, recognising that the nutritional status of the woman at conception has powerful predictive value for the health and wellbeing of the child. It then draws on attachment theory to emphasise that a baby’s social and emotional development depends on the quality of their attachment to their primary care givers. Further, a foetus or baby exposed to toxic stress can, it asserts, have their responses to stress distorted in later life. Such stress arises if the mother is suffering from ‘depression or anxiety…a bad relationship… bereavement.’ The implications are clear; ‘Ensuring that the brain achieves its optimum development and nurturing during this peak period of growth is therefore vitally important, and enables babies to achieve the best start in life.’ If the mother/caregiver cannot/does not give such support during this critical period, the damage will be virtually irreversible.

All the elements of the appeal to neuroscience are thus in place – critical periods, brain growth, synapse number, stress, cortisol levels – plus attachment theory with its focus on the relationship between the child and the primary care-giver. The appeal is certainly there; the question is whether the neuroscience supports it.

Neuroscience, Development and Early Intervention

What of the neuroscience behind Allen’s and the 1001 Days reports? As they emphasise, a baby is born with a lot of brain growth still to do, and much of this post-natal increase reflects the growth of connections (synapses) as the brain wires itself up in an unrolling developmental sequence, with different regions growing at different rates as they ‘come on line’. The Early Intervention assumptions are that: (1) the more synapses the better; (2) poor environments in these critical years permanently reduce synapse number and the brain doesn’t wire up properly; (3) there are critical (or sensitive) periods in brain development, especially, (4), for proper attachment bonds to be formed between care-giver (mother) and infant; (5) ‘Toxic stress’ at this early period has lasting consequences for later development. Neither of the first two is supported by the neuroscientific evidence; the third, fourth and fifth oversimplify very complex relationships between the child’s developing brain and their social and environmental context.

We cannot here discuss this evidence in detail – it can be found in our book, Can Neuroscience Change our Minds (2016) – but will focus on just two, the MRI pictures and toxic stress.

The origins of those MRI images of normality and neglect

Returning to those dramatic MRI images on the covers of the Allen reports and extensively replicated, comparing a ‘normal’ three year old versus one suffering from ‘extreme neglect.’ Their source turns out to be an unrefereed poster presentation by Bruce Perry, of the Child Trauma Academy in Houston, Texas at the 1997 meeting of the American Society for Neuroscience.(1) The images Allen uses are the only ones in the Perry paper, and they show such an extreme difference – far more dramatic for example, than those of children rescued from Romanian orphanages in the 1990s (2) – as to make further questions as to their origin imperative. So we asked Dr Perry. He replied in an email to us in April 2014 that they had not published this ‘initial set of observations’ and that it had ‘become clear that due to a variety of factors, we were really unable to conclude much more than ‘severe neglect impacts brain development.’ The tremendous variability in the ‘nature, timing, pattern of abuse/neglect … led to such a heterogeneous sample’ that they needed to develop methods to ‘better interpret any biomarker or neuroimaging data.’

Nonetheless the Report with its MRI brain images has been widely distributed to public health officers as if they were “good science.” Perry’s influence and his brains have entered UK private sector training programmes such as the Solihull Approach, which offers early intervention courses for social workers, health visitors, nurses and parents. Kid’s Company also used them in its advertising.

Stress and cortisol

Stress is notoriously difficult to define. A little is necessary to respond effectively to the daily challenges of life, too much over too long a period can leave some unable to act at all. And there are huge differences in individual responses. What is a good and helpful level of stress for one person may be debilitating for another. It’s been known since the 1950s from experiments in rodents and monkeys that acute stress in infancy, including what was described as deprivation of maternal care, can have lasting physiological and biochemical consequences, affecting resilience and susceptibility to disease in later life. How far the effects of these extreme experiments can be extended to humans, with our extraordinary capacity for plasticity, of transcending such seeming determinism, is uncertain.

Key to Allen, 1001 days and related programmes is the link between stress and a hormone, cortisol, secreted by the adrenal glands. Cortisol has multiple effects across the body, from regulating blood sugar, salt and water balance to learning and memory. Blood levels of cortisol vary through the day, being highest in the morning, lowest at night, and also across the life cycle from infancy to old age. Furthermore, the levels are quite labile; stress, from the need to meet a sudden challenge, to chronic anxiety and life hazards, all increase cortisol levels at least briefly. Any single measurement is not very informative because of the daily variation, but it’s been found that cortisol accumulates in hair. Hair grows at a centimetre a month, so the cortisol content of that centimetre could be seen as an index of the level of a person’s stress over that month. So some of the Early Intervention protocols propose routine sampling of a baby’s hair to provide an index of chronic stress, thus providing a biomarker for ‘toxic stress.’ However because there are large individual differences in cortisol levels between individuals – ‘baseline levels’ measured mid-morning, may vary fivefold between one person and another, and across different populations –a direct correlation between cortisol in hair and stress levels is hard to make. Exposure to the blue light emitted by electronic devices from smart phones and computers, especially late at night affect cortisol levels and intellectual functioning the following day. Very high levels are associated with endocrine diseases such as Cushing’s syndrome, very low levels with other diseases.

The Early Interventionists tend to ignore such complexities; setting aside individual differences, they assert that high cortisol levels are indicative that an infant has been subject to ‘toxic’ stress as a result of an unsupportive environment. One popular book on the reading list for such programmes, Sue Gerhardt’s Why Love Matters (2004) goes so far as to refer to it as ‘corrosive cortisol.’ Measuring cortisol levels as an index of ‘toxic’ stress, is not dissimilar to looking for a lost key under the street light because nothing can be seen in the darkness.

The doom-laden language of the Early Interventionists continues to imply that a child’s destiny is fixed within these first three years of brain growth and synaptic proliferation, and that poor parenting results in the child’s failure to form secure attachment, with dire consequences both for the child and economic growth. The alarmist claims about rates of brain growth, synapse numbers, sensitive periods and cortisol levels are at best a bridge too far, at worst reliant on ideologically-driven, bad or over-interpreted science.

Inequality, mental capital and neuroscience

Above all they ignore the consequences for brain development and mental capital of the growing inequalities of a society of the 1% obscenely rich and the 99% of the rest. Missing is any recognition of the structural links between a globalised capitalism and intensifying inequality. Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett’s 2009 book, The Spirit Level, demonstrates the socially destructive impact of such inequality on health and wellbeing. The impact is not confined to the poor and the poorest, where parents have no certainty whether they can put a meal on the table for their children, or older people to heat their homes, but to the very fabric of society. Inequality, as Wilkinson and Pickett insist, carries severe and widespread social costs, which can only be met by structural change, about which neuroscience has nothing to say.

References:

Rutter, M. et al (1999) Quasi-autistic patterns following severe early global privation, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 4, 537-549.

Gerhardt, S. (2004) Why Love Matters, Routledge, 2004

Hilary Rose is a sociologist and emerita professor at Bradford University, Steven Rose is emeritus professor of neuroscience at the Open University. Their new book, Can Neuroscience Change our Minds? (Polity), is just published.