Alice Kim and Vickie Casanova Willis (Chicago Torture Justice Memorials)

Ferguson, New York, Florida, Baltimore, Chicago. Everywhere, it seems, Black life matters not, despite the desperate plea “I can’t breathe!”; hands up do not halt the police bullets. A stark power imbalance pervades the culture of policing in the U.S. in urban communities of color. The daily headlines, trending tweets, and the latest video captured by someone’s smartphone all illustrate the brutal, senseless violence perpetrated by the state against African American men and women. Under the guise of serving and protecting, the forces licensed to carry guns and military grade weapons hold the power of life and death in their hands.

Far too many who encounter law enforcement in U.S. cities are left seriously injured or dead. This undeniable fact is played out before our very eyes and at every turn. Youth across the nation have taken to the streets, and even recently to the United Nations, to echo a prior generation’s challenge: “We Charge Genocide.” In Chicago, a decades long struggle to hold police accountable for torturing over 100 African American men is making headlines and history by winning concessions from the city that tortured.

In May 2015, Chicago became the first city in the history of the United States to provide reparations for racially motivated police violence, specifically a group of African American men and women who were tortured by former Commander Jon Burge and his detectives over a span of nearly two decades, from 1972 to 1991. This has only come about by empowering ordinary Chicagoans to organize, advocate, agitate, negotiate, and demand accountability from our city’s elected officials.

First dozens, then hundreds, and even thousands, of conscious citizens responded to the call for reparations by the Chicago Torture Justice Memorials (CTJM) collective. Our work amplified the earlier international human rights initiative and call for reparations from Black People Against Police Torture (BPAPT), a grassroots organization rooted in the African American community. And we built on prior struggles to investigate the torture, remove Burge from the police force, and get justice for his victims. Including veteran activists from these previous struggles, CTJM fought tirelessly with our partners at Amnesty International, Project NIA and We Charge Genocide to ensure that the survivors, their families, and the community harmed by this grossly criminal police behaviour were no longer unheard, without acknowledgment or redress for their suffering.

Without question, this history would not be known to the public if it weren’t for the courage of torture survivors who dared to keep speaking out, even as city officials and the courts refused to believe them. Their cries for justice too long denied remind us how crucial it is to name the issues, perpetrators, victims and survivors. For CTJM, the group that worked with Aldermen Joe Moreno and Howard Brookins to introduce the Reparations Ordinance to the City Council, the act of naming has been essential to building and sustaining our collective struggle for justice and police accountability.

That is why a public memorial is included in the historic reparations package for Burge torture survivors. Along with $5.5 million in financial compensation, psychological and vocational counseling, free education in the City Colleges, a history lesson about Burge torture for 8th and 10th graders in Chicago Public Schools, and an official apology, the public memorial will represent the beginnings of a long awaited and overdue healing process.

[Photo credit: Bronte Price]

Tortured in 1973, Anthony Holmes was one of Burge’s first victims. He was repeatedly electric shocked with a makeshift electrocution box and suffocated with a plastic bag. “Other police was in the room, but nobody helped me,” Anthony said when he testified at the Finance Committee hearing on the reparations ordinance. “The sad part about it is,” he said. “All them years I served in penitentiary, didn’t no one believe what I was telling them.”

Naming the survivors has become an act of memorializing that we have enacted at critical moments in our campaign. We have done this with the understanding that every single name signifies a person whose life was ravaged by torture. And we have done this to acknowledge the courage of the survivors, like Anthony, who refused to be erased.

[Photo credit: CTJM]

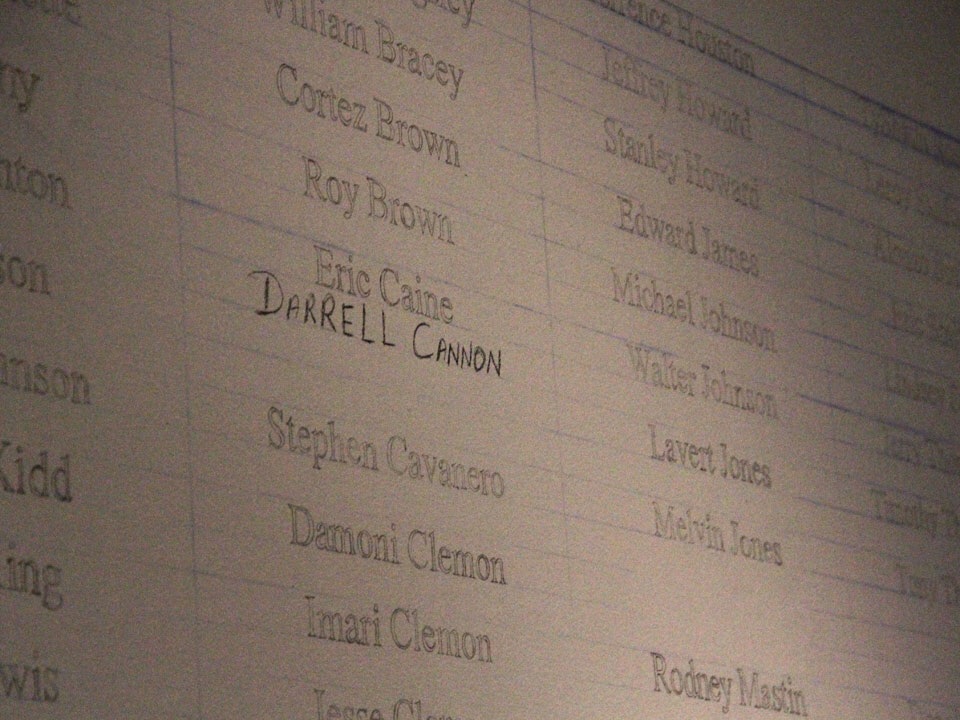

In October 2012, a year before the Reparations Ordinance was introduced in the City Council, the CTJM collective designed a wall of names to memorialize each and every Burge torture case. Our wall of names was one of over 70 speculative memorials in an exhibited we curated entitled “Opening the Black Box: The Charge is Torture.”

As Maya Lin said about the making of the Vietnam Memorial, “The use of names was a way to bring back everything someone could remember about a person.” Our wall of names not only recalled the horrific torture that each survivor experienced, but also all the stories and experiences that comprised each of their lives. Listed collectively, their names were representative of a system that allowed the torture to take place.

Four torture survivors involved in the campaign for reparations – Darrell Cannon, Mark Clements, Anthony Holmes, and Marvin Reeves – joined us at various exhibit events to sign their own names on the wall. With dozens present to witness the act, each time one of the survivors signed his name to the wall, a hush of silence overwhelmed the room. There was power in each individual act of signing, a symbol of their own refusal to be erased.

The power of naming was once again acutely felt in a procession that CTJM and Amnesty International enacted on April 4, 2014, in commemoration of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. Local artists built 119 black flags, each one brandished with the name of a torture survivor and the date they were tortured. Activists carried these flags on a march down the streets of downtown Chicago and gathered at Daley Plaza across from City Hall. At the rally, as the name of every survivor was announced, an activist holding the respective flag silently walked over to stand in a line parallel to City Hall. With this procession, we bore witness to the individual and collective pain of the survivors and demanded that the city take responsibility for the brutal torture that had been inflicted on these men.

Later in 2014 on December 1, facing a heated mayoral election in the new year, reparations activists organized a 3-mile march from Chicago Police Headquarters to City Hall to kick off an intense campaign for reparations. After a spirited march, protesters poured into the entryway of Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s office to deliver 35,000 signatures on petitions calling for reparations, and we created a pop-up memorial right in front of the Mayor’s office. We laid flowers, cards, quilts, photographs down to honor the survivors, and organizers passed out 119 cards, each bearing the name of a torture survivor, to protesters. And then it began; each one, name one. As they called out the name on their respective card, one by one, individual protesters proceeded to add their card to the memorial, a prescient reminder to the Mayor that we would not allow these men to be forgotten.

On Valentine’s Day, we enacted another living memorial following a rousing indoor rally for reparations. In the bitter cold at Daley Plaza, 119 Chicagoans stood outside holding the black flags with the torture survivors’ names on them. Mariame Kaba, who initiated this Valentine’s Day memorial describes it like this, “It was our wall of names, the survivors of a war declared and prosecuted against Black people in a major American city. Everyone stood shoulder to shoulder….The line stretched the length of a block.”

[photo credit: Sarah Jane Rhee]

Kaba points out that it is hard to look directly at torture, but that facing that reality “is the only way that we’ll have any chance of addressing the violence done in our name at home and abroad.”

There is transformative power in naming. The survivors remind us of this, time and time again. Their courage to speak out and their refusal to be erased enlarges the human spirit in all of us.

Alice Kim is a founding member of the Chicago Torture Justice Memorials. She is the Editor of Praxis Center, an online social justice resource center for scholars, activists, and artists. A long time anti-death penalty activist and prison abolitionist, Alice was previously a national organizer with the Campaign to End the Death Penalty and successfully worked towards ending the death penalty in Illinois. Vickie Casanova Willis, MBA, MAT, PhD pre-candidate in Education, is a founding member of Chicago Torture Justice Memorials and Black People Against Police Torture. She is a US Human Rights Network FIHRE Fellow (2014), administrator of the National Conference of Black Lawyers (NCBL) Law Enforcement Accountability Project, and member of the Trinity UCC Justice Watch Team. Casanova Willis actively engages human rights abuses as a cultural worker, marketing/management professional, organizer, and educator. Her leadership with initiatives like First Defense Legal Aid’s “Know Your Rights” community marketing includes education and advocacy to redirect traditional mainstream media and marketing tactics to empower, rather than exploit, communities of color.

Header Image Credit: Chicago Torture Justice Memorials