Eldin Fahmy (University of Bristol)

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent introduction of austerity policies targeting drastic cuts in social expenditure across EU Member States, the issue of youth disadvantage has risen up the political agenda across Europe. For the most part, these debates have focused narrowly on the sharp rise in youth unemployment which in many member states reached unprecedented levels in the post-2008 period. However, wider issues of youth marginalization, for example, associated with low pay, employment precarity, lack of opportunities, poor living conditions and housing insecurity have received less policy attention.

In particular the growth in poverty and deprivation amongst young people has remained largely uncharted. Drawing on data from the 2012 UK Poverty and Social Exclusion Survey, this article examines the nature, extent and social distribution of youth deprivation and social exclusion amongst 16-29 year olds living in Britain. In doing so, it seeks to address some vital questions concerning youth disadvantage and how this has changed over time, including:

• What are the ‘necessities of life’ for youth in Britain today, and how many young people experience deprivation according to these standards?

• How does youth vulnerability to deprivation compare with older adults?

• How have rates of youth deprivation changed over time compared with 1999?

• How many young people are experiencing wider forms of social exclusion?

The 2012 PSE-UK is largest and most comprehensive survey on deprivation and social exclusion ever conducted in the UK and updates earlier comparable studies conducted in 1999, 1990 and 1983. These studies adopt a ‘consensual’ approach to poverty which reflect public views on minimally adequate living standards.

This approach can advance our understanding of youth poverty disadvantage in two important ways. Firstly, by supplementing income data with direct measures of living standards and exclusion from customary norms, the survey give us an insight into the extent and social profile of youth disadvantage which extends far beyond relative low income alone. Secondly, by drawing on data 1999 and 2012 collected using a comparable methodology it is also possible to examine how the nature, extent and distribution of youth deprivation and exclusion have changed over time in the UK, and how they compare with the situation of older adults.

What are the necessities of life for UK youth and how many lack them?

To establish the ‘necessities of life’ in 2012, a nationally representative sample of the public were asked to identify from a list of 35 items and activities those which ‘were necessary and which all people should be able to afford, and [to] which they should not have to do without’.

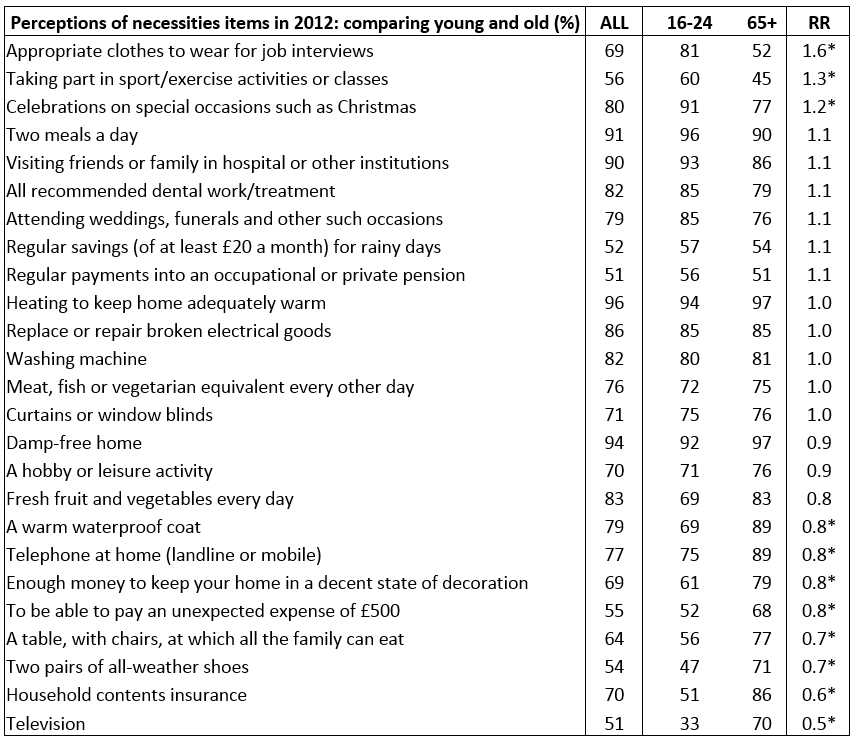

Table 1 shows the proportion of young (aged 16-24) and older (aged 65+) respondents describing a range of

selected items and activities as ‘necessities’ for all adults in Britain in 2012. Whilst there is some disagreement on specific items (e.g. clothes for job interviews, insurance, TV), in general young people mostly share similar views to the wider public on what it takes to avoid poverty in Britain today. These items reflect an understanding of poverty that extends far beyond a minimalist concern with material subsistence and physiological functioning to encompass social needs, norms and expectations.

How does the extent of youth deprivation compare with that of older adults?

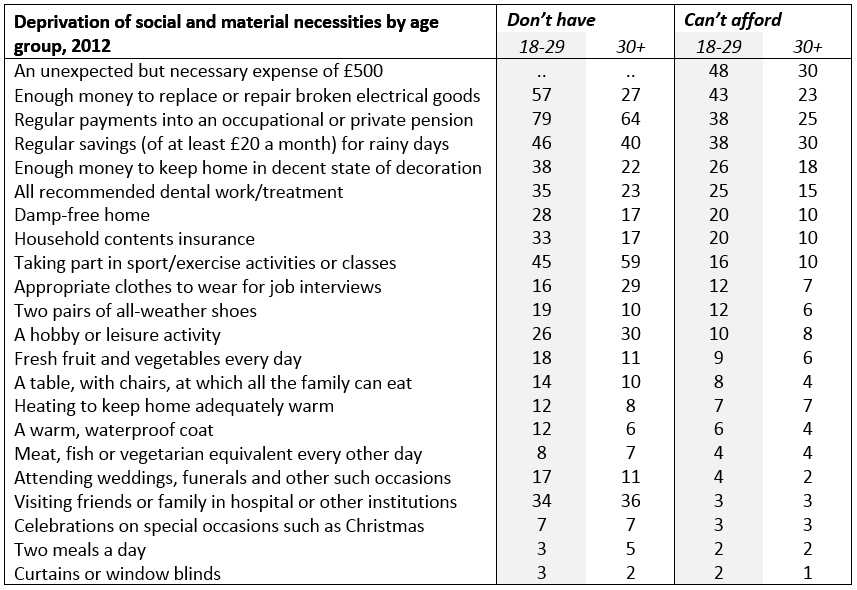

Table 2 shows the percentage of young respondents (aged 18-29) and older respondents (aged 30+) in Britain

lacking different ‘necessities’as determined by the UK public in 2012. These data show that for virtually every measure, the percentage of young people lacking items is higher than for older adults. It is sometimes argued that simply measuring whether individuals and households lack items and activities is not informative about impoverishment but may merely reflect different preferences. For this reason we also examine whether respondents report lacking items because they cannot them. Using this more discerning measure of financial constraint reveals an even starker picture: there is not instance where a greater percentage of older adults report being unable to afford contemporary necessities in comparison with young people aged 18-29.

lacking different ‘necessities’as determined by the UK public in 2012. These data show that for virtually every measure, the percentage of young people lacking items is higher than for older adults. It is sometimes argued that simply measuring whether individuals and households lack items and activities is not informative about impoverishment but may merely reflect different preferences. For this reason we also examine whether respondents report lacking items because they cannot them. Using this more discerning measure of financial constraint reveals an even starker picture: there is not instance where a greater percentage of older adults report being unable to afford contemporary necessities in comparison with young people aged 18-29.

How have rates of youth deprivation changed over time compared with 1999?

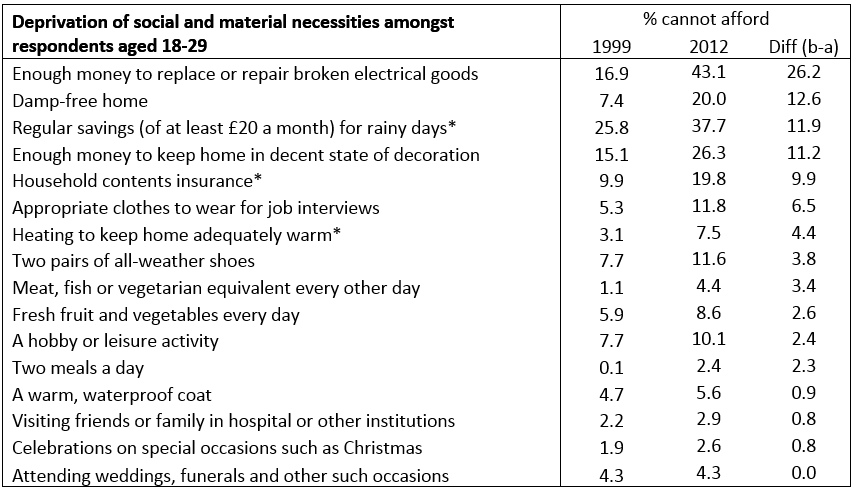

Table 3 compares the percentage of young respondents (aged 18-29) reporting being unable to afford different

necessities in Britain in 1999 and 2012. These data reveal a dramatic increase in the extent of youth deprivation in Britain over this period. Whilst it is not unusual to observe an increase in relative deprivation (i.e. where we are using different set of indicators at different points in time to reflect changing societal standards), it is much less common to observe a clear increase in the extent of absolute deprivation (i.e. based upon the same items and activities measured at different time points).

necessities in Britain in 1999 and 2012. These data reveal a dramatic increase in the extent of youth deprivation in Britain over this period. Whilst it is not unusual to observe an increase in relative deprivation (i.e. where we are using different set of indicators at different points in time to reflect changing societal standards), it is much less common to observe a clear increase in the extent of absolute deprivation (i.e. based upon the same items and activities measured at different time points).

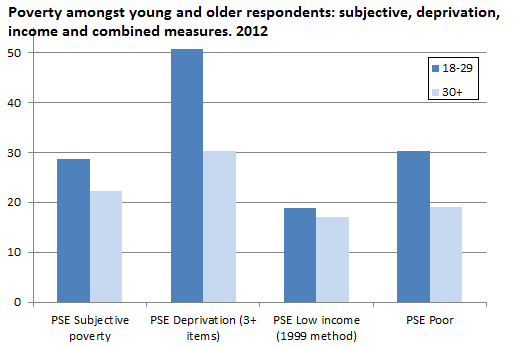

The measurement of poverty is of course not an exact science. Different measures are best suited at tapping different aspects of poverty and for this reason it is often prudent to compare results across different measures. Figure 1 compares subjective, deprivation, income and combined low income/deprivation measures for

young (aged 18-29) and older (aged 30+) respondents in Britain in 2012. This reveals low household income to be a rather poor guide to young people’s objective living standards and subjective perception of their own circumstances. Nevertheless, on every one of these measures young people are especially disadvantaged. Indeed, more than half (51%) of young people aged 18-29 living in Britain lacked three or more basic necessities of life as determined by the UK public in 2012.

Policy implications: what about youth poverty?

These data document both the increasing extent of youth deprivation and impoverishment relative to the situation for youth in 1999, and the scale of the problem facing today’s young people in comparison with the situation of older adults. The impacts of austerity for young people are increasingly being acknowledged amongst the wider policy community, and the problem of youth unemployment has (understandably) been an increasing focus of policy concern in the UK, across the EU, and globally. However, it would certainly be a mistake to reduce the complexity of young people’s circumstances to a focus on labour market transitions (and specifically transitions into paid work) for three reasons. Firstly, acknowledgement is needed of the interdependencies inherent in young people’s experiences of growing up and the impacts these have upon poverty vulnerability (e.g. in relation to housing circumstances, partnership arrangements, support networks, etc.). Secondly, an overly narrow focus on activation and labour market insertion obscures the extent of in-work poverty and disadvantage for young people associated with low wages, job insecurity and poor working conditions.

Finally, and most importantly, a focus on labour market transitions obscures the centrality of the experience of deprivation for many young people in the here and now: it is a problem of ‘being’ and not simply of ‘becoming’. The extent of youth deprivation is a problem not only with regard to its potential long-term impacts (which can be serious) but as an issue affecting young people’s current circumstances and living conditions which requires urgent policy attention. To date, policy action in the UK to tackle disadvantage has focused heavily upon the problem of child poverty, perhaps on the basis of an implicit assumption that entry into the labour market at age 18 will provide young people with the means to secure their own salvation. These data suggest that if anti-child poverty initiatives are to achieve their potential they need to be supplemented with a coherent and comprehensive strategy to support young people’s transitions to adulthood which takes seriously the problem of youth deprivation and youth poverty in Britain.

Eldin Fahmy is Senior Lecturer in the School for Policy Studies at the University of Bristol, where he is Head of the Centre for the Study of Poverty and Social Justice. He is a member of the ESRC-funded 2012 UK Poverty and Social Exclusion Survey research team (Ref: RES-060–25–688 0052). Eldin has research interests in the study of poverty, social exclusion and disadvantage including a specific interest in youth disadvantage and youth transitions.