Emily Wykes (University of Nottingham)

“With a name like Patel, and her ethnic background, she won’t be working anywhere important where she can’t get the time off” (The Guardian). This recent comment by Richard Hollingworth, a district judge, about the availability of a harassment victim to attend court, may have made newspaper headlines, but it did not surprise me.

My research is based upon 32 semi-structured interviews with participants (mainly women) who had either changed their surname from one they deemed ‘white British’ to one they felt was ‘foreign’, or vice versa, or had been married to someone with a surname they described as different to their own racial/ethnic identity. The idea behind my project was to speak to those who were able to compare their experiences of bearing a surname constructed as ‘white British’ and one understood as ‘foreign’ in the UK context.[1]

What was particularly interesting about my findings in the light of the judge’s comment was that upon changing their surname to one they felt was perceived to be different to their embodied ‘racial’ identity, many of my participants reported that their everyday experiences, and others’ reactions to them as individuals, had also altered.

For example, Kayla Brackenbury (black British; Zimbabwean born and raised; Zimbabwean maiden name) said that when she has not been physically present with her ‘white British’ married name (that is, when her skin colour has not been known), she has found that her married surname has made quite a significant difference to her everyday life. This does not only link to increased chances of being called for job interviews, as has been highlighted by previous research, but also relates to subtler experiences. She said that if people do not pick out her Zimbabwean accent on the phone, ‘you find that the tone of the voice, and the way people are speaking to you…is a bit better than [with] my maiden name’.

Moreover, Kayla explained that her ‘credit file has improved, because I’ve got a new name…I’m getting…offered, more credit…just compared to [what I was offered] as Kayla Manyika [her maiden name]’. In addition, Kayla said that to have a ‘white British’ surname makes her appear more bona fide British in some contexts. It gives her that (albeit imperfect/partial) link to the privileges of being ‘white British’, which she felt her old surname did not have.

On the other hand, the ‘white British’ participants who had taken a ‘foreign’ surname described how they had gone from having an ‘invisible’ name and ethnic/’racial’ identity, and unquestionable access to the privileges of being conceived as ‘white British’, to having these criteria doubted.

Natalie Mustapić (white British) who had previously borne a ‘white British’ surname, spoke of how, since taking her husband’s Croatian surname upon marriage, she is now often stopped and searched at British and international airports. She described how this started happening before 9/11 and therefore could not be attributed to increased security measures. She explained that now when she is ‘negotiating with authority…it’s just that extra question mark…more arising because of the experience [of] crossing borders, that you’re not quite as British as you were’.

Abigail Koslacz (white British) had formerly had a ‘white British’ surname, and took her husband’s ‘Polish’ surname upon marriage. Abigail, a teacher, indicated that when she worked at her previous school, where she had borne both her former surname and subsequently her married name, she did not have any issues with her surname. However, since moving school, where she had only been known by her married surname, she said that:

…there was this assumption at one point, when we had a Polish girl at school who arrived with very little English, that I would teach her some [chuckles]…[Polish] and work with her, and I did actually get her a GCSE in Polish but I only know twelve or maybe 20 words in Polish, I don’t speak Polish! And that was quite funny, suddenly I had this talent that I didn’t know about, just because I’d inherited a Polish surname…so, yeah, I do think people have this expectation that I’m maybe a little bit more exotic than I was….

It seems quite a leap, to go from hearing someone’s surname to using that surname as a gauge for their abilities in a different language. Indeed, Abigail described how colleagues had been asking her where her surname was from, and that they had been able to remember it was ‘Polish’. Apparently, they could not remember that she herself was not Polish, despite her having also told them this. By changing her surname Abigail had seemingly moved from her position of undoubted ‘white Britishness’, when using her maiden name, into one of a certain Otherness, whereby she would magically have imbibed the ability to speak ‘anOther’ language as a consequence of taking a ‘foreign’ surname.

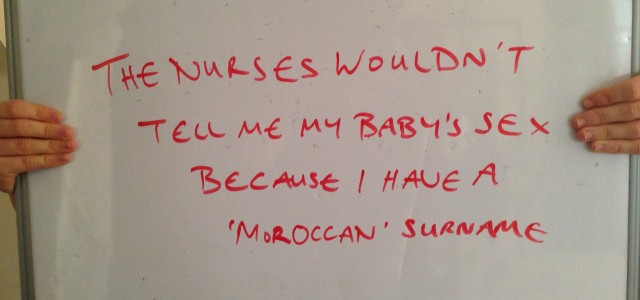

Additionally, Suzanne Balester (white British) described how when she had formally held a ‘Moroccan’ married surname, she had attended several pre-natal appointments at her local hospital. Suzanne said that the nurses refused to tell her the sex of the baby. For Suzanne, this refusal was based around stereotyped ideas of what her ‘Moroccan’ surname represented: that she would prefer to have a male child and that she would potentially wish to abort a female child. Suzanne said: I definitely felt that that was a real discriminatory issue…and they never told me [the baby’s sex]…and I asked a few times’.

Whilst there are many potential discussion points in relation to the quotations/examples I have provided, arguably the major theme that holds these examples together is that surnames are apparently more than just an individual marker of identity. They are seemingly understood in ethnic/‘racial’ terms and internal characteristics are accordingly expected of, or attributed to, the name bearer. This idea takes us back to race literature, which has long documented the essentialised equation of ‘race’ to characteristics such as intelligence, beliefs and morals.

The ethnicisation/racialisation of these surnames is obviously context specific. My data suggested that a person’s name, skin colour and accent interact in determining the ethnicisation/racialisation of that person. For instance, Kayla’s responses intimate that, should her Zimbabwean accent and ‘black’ skin colour be known, this would revoke any privileges she may have from having a surname constructed as ‘white British’. Likewise, with the ‘white British’ participants who had ‘British’ accents, in some circumstances these aspects of their identity would outweigh any disprivilege encountered on the basis of bearing a ‘foreign’ surname.

It may appear that my participants’ experiences of bearing ‘foreign’ surnames in the UK – and indeed, the comment made by the district judge – are representative of merely banal episodes of everyday racism. Indeed, it is perhaps easy for us to accept that something is ‘racist’ if a person uses ‘racial’ slurs (BBC News). Yet surely far more common are the kinds of incidents I have presented above, episodes which can be labelled as ‘micro-aggressions’. They may not seem blatantly racist and it may sometimes be difficult to describe them and to explain why they are ‘racist’. Cumulatively, though, such micro-aggressions may be just as damaging to those who suffer them, as those incidents which are legally/pervasively considered more explicitly ‘racist’.

It is also important to consider that the episodes I have referred to have only perhaps come to light, or have been readily observable by the participants, because they have had something to compare their experiences to. By bearing surnames deemed to be representative of different ethnic/‘racial’ identities, they have been able to consciously contrast how their surnames have affected their everyday lives.

The judge’s comment with which I began this article is an unusually explicit example of racialisation: what are the everyday impacts of other judges or indeed teachers, policemen, or other people in positions of power, who may (consciously or subconsciously) see people in such racialised terms?

Note:

[1] Pseudonyms have been used; the ethnic/‘racial’ identities and name descriptions were provided by the participants.

Emily Wykes is a teaching associate in the School of Sociology and Social Policy at the University of Nottingham. She completed her PhD in 2013 0n ‘The Racialisation of Names: Names and the Persistence of Racism in the UK’. Her research interests include: ‘race’, racism, racialisation and whiteness. Another blog by Emily is here.