Prakash Kashwan (University of Connecticut)

The results of the recently concluded Delhi state assembly elections have been referred to as a political earthquake: the “start-up” Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) routed the ruling Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) by a margin of 67-3 in a 70 seat assembly. A common denominator in the commentaries published in international media is to examine whether the populist politics that the AAP apparently stands for will hurt the reformist impulses identified commonly with the BJP-led federal government (see here & here). I argue that such juxtaposition of AAP’s populism against the BJP’s reform agenda is based on a fundamental misreading of Delhi’s remarkable electoral verdicts. A proper understanding of the verdict requires a contextualized understanding of both India’s electoral politics and the political economy of reforms.

The exit polls showed that compared to the results of the 2013 Delhi elections, the BJP lost only one percentage point of Delhi’s vote share. As Rajdeep Sardesai points out, the AAP secured the bulk of the vote that the Congress lost, and essentially all of the incremental vote of Muslims, Dalits, and a section of the middle class. The Delhi voters voted strategically with the intention of voting AAP in and the BJP out. A CSDS poll showed that AAP outsmarted the BJP in every age and income segment and equally among men and women, despite the BJP putting up a women as its chief ministerial candidate. The poorer the voter, more likely that they voted for AAP. The younger the voter, more likely that they voted for AAP. The BJP’s rejection by a majority of voters, including the most educated and pro-reform young voters has insights worthy of a careful examination.

Many in the international media, who accept the Prime Minister’s and the BJP’s claims that they fight elections on the plank of a “growth agenda”, have tried to insulate Prime Minister Modi and his reformist agenda against the critiques implied in these election results (see here, here, & here). This is a continuation of the trend of the international media’s misreading of the electoral mandate of India’s 2014 general elections on several accounts, as I argued here and here. While the then Prime Ministerial candidate Modi went around the country promising effective delivery of civic amenities, including rural and urban infrastructure , international media read a triumph of the markets in Modi’s electoral victory. In fact, in every election rally that Modi addressed during the 2014 general elections, he pledged “to bring back the black money stashed [in Swiss bank accounts] and give Rs 1.5 million to every Indian.” Now, “black money” is not an issue that pro-market advocates are usually passionate about. Instead, corruption is the quintessential populist issue with a universal appeal.

During the Delhi election campaign, BJP also made the same promises for which the commentators have called AAP a populist party. The BJP too had promised to halve power tariff and provide housing for the slum-dwellers. BJP’s electoral campaign was as populist as, if not more than, the one that AAP ran. Moreover, Prime Minister Modi’s credibility as an efficient administration has also taken a hit in recent times. Pradeep Chhibber and Rahul Verma cite evidence from the Cicero Associates opinion polls, which shows that 48% Delhi’s voters think that the Prime Minister has made lots of promises but has not delivered on them. More importantly, even the staunchest Modi supporters suggest that “nothing has changed on ground in first nine months of the Narendra Modi government”.

The AAP also used the Delhi campaign to hold the Prime Minister accountable for his numerous promises. As the conversation that NDTV’s Ravish Kumar had with AAP’s foot soldiers revealed, during the election campaign, the AAP cadre carried folders full of news reports to expose fundamental flaws in the lofty declarations that the Prime Minister had been making day in and day out. Delhi residents interviewed by NDTV correspondents asserted, “It was important to teach the BJP a lesson; they had become too arrogant”. It is therefore reasonable to conclude, as Ashutosh Varshney did recently, that Delhi voters “trusted Arvind Kejriwal over Modi.”[1]

In a nutshell, the Delhi verdict does not reflect the victory of a populist party pitted against a reformist party, as some commentators have argued. Instead, the Delhi voter has voted emphatically for the classical Indian electoral issues, often captured in the phrase, bijli, paani, and sadak (power, potable water, and roads). It is unfortunate that this ‘economic agenda’, a phrase that I use deliberately in this context, which is of concern to a majority of voters, is trivialized to paint AAP as a populist party. Improvement of the civic infrastructure is critical even if market-led growth happens to be one’s calling. Investment in health and education have been the motors of economic growth in China and east-Asian tiger economies. In India, both BJP and Congress leaders have failed to grapple with these challenges. Instead, they have taken the path of least resistance which comes studded with corporate contributions to party funds and cheap brownie-points flaunted in global investor summits.

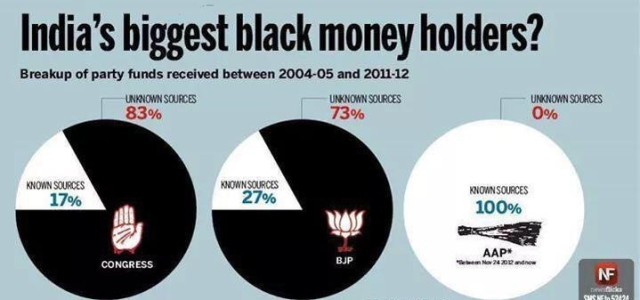

An unprecedented growth in crony capitalism has been one of the key outcomes of India’s so-called market reforms since the early 1990s. As the former chief election commissioner remarked, crony capitalism is intertwined with India’s electoral politics. One of the highlights of the 2014 general elections was the enormously expensive campaign that the BJP unleashed. Both BJP and Congress are opposed to the proposals to bring political parties under the ambit of the Right to Information law. On the other hand, AAP has set extremely high standards by disclosing information about the contributions to party fund on its website. By making the corporate-political party nexus as one of the central planks of its electoral campaigns, the AAP has helped create a demand for campaign finance reform and the need to hold political parties accountable.

Similarly, the AAP’s position regarding Delhi’s power tariffs relates to important debates about reforms in the power sector. Independent research shows that Delhi’s privatized power sector is replete with inefficiencies and unfair trade practices. Reports suggest that power companies may have installed faulty meters that systematically inflated the readings of power consumption, and hence the amount that consumer paid. By bringing the potentially large scale corporate corruption involved in Delhi’s privatized power utilities into the realm of electoral politics, the AAP has questioned the master narratives that falsely equate privatization to competence and efficiency. During its 49 day government in Delhi last year, the AAP leaders instituted an audit by the government auditors, a process that reportedly slowed down during the past eight months of Delhi administration under the BJP-led federal government.

The AAP’s electoral campaigns thus rely on issues that are fundamental to the successful implementation of reforms in the delivery of basic amenities. This is not to suggest that the solutions AAP has offered are perfect. Consider the proposal for the supply of 700 liters of lifeline water per day, an idea that is based on the World Health Organization benchmark of 125 liters of water per person per day. The studies conducted by Dunu Roy, the director of Delhi-based Hazards Center, suggest that a figure of 100 liters of water per person per day is sufficient across all income groups in Delhi. Considering the importance of conserving valuable natural resources, it would be desirable to rethink the specifics of how much of the needed supply of water should be made available free of cost to every citizen. Other alternative exist, such as a minimalist pricing structure, or a sliding scale in which the middle and upper class residents pay a higher tariff than they expect the poor to pay.

Accordingly, the idea of ‘life-line water’, which resonates with the United Nations’ recognition of water and sanitation as fundamental human rights cannot be dismissed as populism. More so, because in the status quo scenario, it is the poor who pay a steep price for water delivered by the tanker mafia, while the elite residents of the Lutyens’ Delhi get a comparatively more reliable and abundant supply of highly subsidized water supplies. As Jean Drèze has argued repeatedly, ironically, many of those who argue against the state-led provision of essential services to a majority of citizens, are often the exclusive beneficiaries of a variety of largesse that are built into the status-quo. This is the real essence of the politics that AAP has introduced to the nation’s political landscape.

To conclude, Delhi elections are a reflections of the prime minister’s failure to engender effective reforms, and of the AAP’s ability to convince voters about the superiority of its proposals to reform the reforms that have not worked for Delhi and its residents. Even if the “AAP just happened to be the vehicle” for the articulation of simmering discontent among a majority of Delhi’s citizens, as a veteran political commentator argues, the people of Delhi found AAP to be the best among the options available to them. The task for all serious advocates of reforms is cut out: rethink the types of reforms that would help improve the quality of life for the majority of citizens and how elected governments are held to account.

Note:

[1] Some readers may notice significant similarities between the specific pieces of evidence and the underlying analytical focus of this essay and Varshney’s essay published in of the Indian Express. Please note that other than the specific quote reference here, which is being included during the second round of editing, this essay was written and submitted to the editors prior to Varshney’s commentary was circulated online on February 18. These similarities do lend independence validation of the arguments I make here.

Prakash Kashwan is Assistant Professor of Political Science at University of Connecticut, Storrs. His teaching and scholarship focuses on comparative politics, political economy, and international environmental policy and politics. He may be reached via email at prakash.kashwan@uconn.edu and his recent publications may be accessed via https://uconn.academia.edu/PrakashKashwan