Zrinka Bralo (Migrant and Refugee Communities Forum)

Immigration is not a problem. How we deal with it is. And I don’t mean to suggest that talking about immigration is simply racist. Some of it is xenophobic too. We hear about enforcement, border controls, increasing numbers, a small island, and responses such as Go Home vans or Don’t Come to Britain Campaigns. These are, some would say, phantom problems that are being addressed in often very costly ways, and it is the migrants who have to bear the brunt of illiberal policies that pay the highest price.

Credible evidence about the impact of immigration, gathered by independent academics, media and advocates, tell a different story. In the last few years, as anti-immigration rhetoric has been on the increase, a number of immigration myths have been debunked: immigrants don’t steal housing, don’t steal jobs, don’t claim benefits, don’t hold back other children in schools, and don’t abuse the NHS as health tourists. Around half of foreign born citizens have become British nationals. And finally, we might be a small island, but we are not overcrowded. Don’t take my word for it – it is all in hyperlinks.

The fact is that people do not respond to facts, especially when it comes to immigration. We are all capable of holding completely opposing views at the same time; it is called cognitive dissonance. Our politicians suffer from ‘epistemological closure’ as described by Paul Krugman: “Republicans know many things that aren’t so, and no amount of contrary evidence will get them to change their minds.” But that does not mean we can just give up on facts. Anti-immigration opinions, with some very dangerous undertones, are gaining traction, not only here in the UK, but across Europe. We have reached a very serious threshold where uninformed and prejudiced views are affecting the lives of millions of people, and for the 50 million people forced out of their homes this is a matter of life and death, not only in Syria but here in the UK too.

Am I just scaremongering? Perhaps. But as someone who has survived a genocidal war only two decades ago, the question is: what if I am right? Am I not just trying to shut down the immigration debate with my political correctness? I am not, simply because what we have in the UK, most of the time, is not a debate. It is an argument: no one is listening and no one changes their mind at the end of the conversation. Immigrants usually don’t have a say, and if they do, they are portrayed within a power and privilege framework in which they are projected as being the ‘other’ – a threat, a burden or a victim. I don’t want to shut down debate or even argument. But it would be valid to engage in an informed and constructive debate about immigration in Britain, but more importantly to do something constructive too. I am most concerned with politicians and the media who spread distorted stories about immigration, because they believe there is something to gain from the stigmatisation of immigrants and minorities.

On a positive note, there are a significant number of people who understand that immigration is complex social phenomenon, and as voters, readers and viewers we can proactively engage in the process of change. Let me give you an example of what I think needs doing. A few years ago I was a Commissioner of the Independent Asylum Commission. In the process of gathering evidence, we heard from hundreds of witnesses, including four former Home Secretaries. I asked all of them the following question about policy of dispersing asylum seekers out of London:

“What was your communication strategy in relation to dispersal of asylum seekers?”

All four Home Secretaries told me about leaflets that were translated into a number of languages to help newcomers. But none spoke of how to communicate with local residents about how to engage with a variety of new neighbours. With a bit of planning, with a bit of investment and a bit of engagement of civil society, as was done for Vietnamese and Bosnian refugees, we could have faster and more effective integration, beneficial for both. Remember, it’s good to talk. Instead, we hear about enforcement and controls, which is not just about keeping people out, it is also about making life difficult for those who are here. In 2013 Sarah Teather MP, blew a whistle on an internal ministerial group originally called ‘the hostile environment working group’.

The group, renamed as ‘the inter-ministerial group on migrants’ access to benefits and public services’, has come up with proposals, such as forcing private landlords (private renting is a largely unregulated enterprise) to check the immigration status of their tenants or face a hefty fine. This proposal, together with restrictions in accessing health care and a ban on driver’s licenses, has now been enshrined in the law. The most troubling aspect of this overly zealous enforcement regime is an increase in the detention of refugees and migrants. From 1993 to 2004 detention has expanded rapidly, from 250 places to 3,397 places in 2012, with a significant proportion of detention centers under private operation. In 2013 more than 30,000 immigrants were held in immigration detention, with no judicial oversight, no time limit, and very poor access to legal advice. This is the result of harsh policies but also of the administrative convenience of poorly functioning system. Add to this inequity the serious allegations of sexual abuse at one detention center and the horror of the treatment of those seeking refuge and asylum is further compounded.

The estimated cost of detaining one person for one day in 2010 was £120. With 3,400 people in detention every day, the daily cost comes to £420,000 (using 2010 and 2012 figures). Add to that most recent revelation that £16 million had to be paid in compensation for unlawful detention in the last three years, and we are talking about 100s of millions of pounds out of our taxes every year. Is this effective use of public money, and are we sure we want this done in our name? The trauma that this system inflicts on human beings is immeasurable in monetary terms, and perhaps can never be completely undone.

As a part of this incongruous system of regulation, asylum seekers are being forced into destitution: not allowed to work, often prevented from volunteering, not allowed to study, forced to live in designated shared, often substandard, accommodation, and to survive on as little as £5 per day, given to them not in cash, but in a specially made Azure card which can only be used in designated shops. So taxpayers’ money is used to pay a profit-making company to produce, administer and manage these cards.

The current backlogs in processing migration requests is reportedly ‘shambolic’ with applications being stuck in the system for extensive periods of time long time. Further, bureaucratic incompetence is reflected in the £224 million taxpayer bill in 2014 on the failure of an e-Border IT system contracted out to a private firm. The costs of enforcement – human and economic – are immense. Does it have to be this way? Is there an alternative to this approach that seems out-of-step with a world that is increasingly mobile and connected? Here, I am suggesting something apparently radical and controversial: accepting that immigration happens as a normal human and social experience of change, and that it is possible to deal with it strategically and positively.

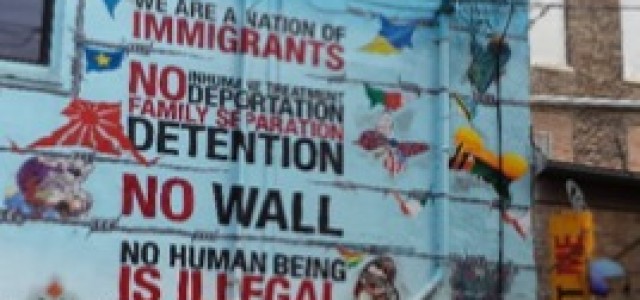

While this may seem like an idealistic stance, it can be done. Last summer, for example, while in the US on a Churchill Fellowship, I observed the Fair Immigration Reform Movement deliver results through community organising and genuine participation of immigrants in democracy. In addition, the systems of enforcement imposed by the state are failing, and are subject to momentous revisions. The US Secure Communities programme (which is mirrored by enforcement and deportment practices in the UK) has been shown to have failed miserably. And in an unprecedented advance in 2014, Obama passed an executive order that effectively legalised millions of undocumented migrants. Changes in legislation affect changes in practice and a number of states are now issuing drivers licenses to undocumented migrants. In California, some undocumented professionals are being issued licenses to practice.

There are many differences between migration and regulation in the US and UK, but there are two things in a long and difficult campaign that was fought in the US that we can replicate: organise and vote.

I hope you will join me in doing both.

Zrinka Bralo is a head of the Migrant and Refugee Communities Forum in London. Since she arrived to the UK as a refugee from besieged Sarajevo in 1993, she led numerous campaigns for refugee and migrants’ rights. She served as a Commissioner on the Independent Asylum Commission, the most comprehensive review of the UK protection system. She is the founder of the Women on the Move Awards and a winner of the 2011 Voices of Courage Award by the Women’s Refugee Commission in New York, for the work with refugees in urban areas. She holds MSc in Media and Communications from London School of Economics and is 2014 Churchill Fellow.

Image Credit: A wall graphic in Chicago (taken by the author)