Image: British Library, Royal MS 12 C. xix, Folio 6r

Daniel Neep (Georgetown University)

‘Do Iraq and Syria no longer really exist?’ exclaimed a recent post on the Foreign Policy blog in tones of breathless alarm. The advance of Islamic State across the two countries has been relentless, matched only by the speed with which Foreign Policy’s answer to this question is itself swallowed up on its website by those ubiquitously insurgent pop-up ads for discounted subscriptions to FP Magazine. With the bloody impasse of the Syrian conflict, the evident weakness of the Iraqi armed forces in the face of the ISIS threat, and pinpointed US airstrikes that persistently prick holes in Levantine sovereignties, the international commentariat has begun to wonder whether Islamic State’s goal of smashing the Sykes-Picot borders of the Middle East might actually be the best solution for the future of the region.

‘The end of Sykes-Picot?’ asks Itamar Rabinovitch in a paper for the Brookings Institution: ‘The unravelling of the current political order in the core of the Middle East may reshape the strategic landscape.’ ‘Is it the end of Sykes-Picot?’ inquires Patrick Cockburn in the London Review of Books. ‘Sykes-Picot is dead!’ exclaims Lebanese politician Walid Jumblatt, somewhat dramatically, to the Independent’s veteran journalist Robert Fisk. The newfound fluidity of the region’s established borders has become an idée fixe of the current debate, much to the chagrin of indignant historians, who point out that the Sykes-Picot agreement of 1915 was never actually implemented in the first place. The borders that exist today in the Levant were, they point out, laid down at the San Remo conference of 1920 and, in any case, were neither entirely artificial nor wholly external impositions (as scholar Reidar Visser explains in his article ‘Dammit! It is not unravelling!’). Such insignificant concerns as accuracy, of course, have never clouded the commentariat’s visions of the Middle East. The symbolic import of the phrase ‘Sykes-Picot’ suggests that this trope has become a permanent fixture in how we imagine the region’s political landscape.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, showing the proposed division between the direct (coloured) and indirect (uncoloured) spheres of influence agreed between France (A) and Great Britain (B) in the Asian lands of the Ottoman Empire (Source).

Criticism of the ‘Sykes-Picot’ settlement largely revolves around two arguments. The first points out that the new states were carved from the carcass of the Ottoman Empire after World War One without regard for pre-existing social, economic, political or cultural alignments. In practice, however, rejection of the so-called Sykes-Picot settlement focuses on the non-correspondence of actually existing states and the latent divisions of communal identities such as ethnicity and sect. (The poor economic viability of the new states, on the other hand, is rarely referenced in the artificiality debates, despite the fact that struggles over political economy invariably underpin episodes of ethnic and sectarian tension). Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq are often taken as exemplars of the category of artificial state: each of these states is putatively identified as a chaotic mishmash of different sectarian and ethnic groups with few common loyalties. A society that contains religious and ethnic diversity, it is implied, produces structural instability on the political level.

The second argument against the ‘Sykes-Picot’ settlement is that the inherent artificiality of these post-Ottoman states has prevented them from winning the consensual support of their populations. To compensate for their lack of natural legitimacy, state-builders in Iraq and Syria resorted to coercion and repression, producing authoritarian institutions of government that were brutal yet brittle, without real roots in society – ‘fierce’ states, as scholar Nazih Ayubi memorably called them. From this perspective, the artificial states of the Middle East are not only politically unstable, but inherently inhospitable to democracy.

This line of analysis leads to what seems to be a logical solution for the apparently endemic crisis of the Middle East: if we can redraw the map to re-align state borders with social borders, then we will not only solve the problem of ethnic and sectarian violence, but we will also remove one of the structural obstacles that prevents authoritarian regimes in the Middle East from transitioning to democracy. Natural states with natural borders will succeed, we are told, where artificial states have failed.

On the Redrawing of the Middle East:

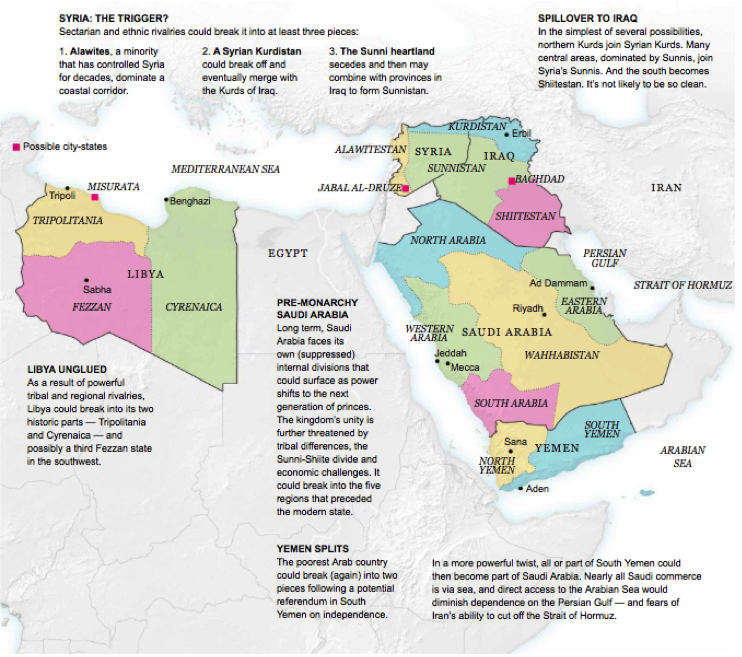

But how exactly to redraw borders in the Middle East to reflect the supposedly naturally occurring, ‘organic’ communities of the region? Fortunately, numerous proposals have been outlined by a long succession of journalists, academics, and think-tank analysts, usually based in North America and Europe. The most well known project to have been published in recent months is journalist Robin Wright’s article, ‘Imagining a Remapped Middle East’ which appeared in the New York Times in late 2013.

‘The map of the modern Middle East […] is in tatters,” Wright tells us. ‘The centrifugal forces of rival beliefs, tribes and ethnicities—empowered by unintended consequences of the Arab Spring —are also pulling apart a region defined by European colonial powers a century ago and defended by Arab autocrats ever since.’ Taking the civil war in Syria as the starting point for the unraveling of the region, Wright argues that ‘Syria has crumbled into three identifiable regions, each with its own flag and security forces. A different future is taking shape: a narrow statelet along a corridor from the south through Damascus, Homs and Hama to the northern Mediterranean coast controlled by the Assads’ minority Alawite sect. In the north, a small Kurdistan, largely autonomous since mid-2012. The biggest chunk is the Sunni-dominated heartland.’

‘How 5 Countries Could Become 14’ (Source).

Wright goes on to suggest that other states that lack a ‘sense of common good or identity’ are also vulnerable to having their borders remapped. Libya, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq are all potential candidates for fragmentation along ethnic, sectarian or cultural lines, alongside uniquely heterogeneous or uniquely well-armed ‘city-states’ such as Baghdad or Misrata, and unusually homogeneous micro-regions such as the ‘Jabal al-Druze’ in southern Syria. Out of the five countries discussed in the article, as many as 14 new political entities might possibly emerge. ‘A different map would be a strategic game changer for just about everybody,’ Wright suggests, ‘potentially reconfiguring alliances, security challenges, trade and energy flows for much of the world.’

Wright is not alone in her conviction that redrawing borders in the Middle East has ameliorative potential. In a 2008 article in The Atlantic, Jeffrey Goldberg weaves together tales of encounters with Kurdish peshmerga fighters, al-Qaeda prisoners, and DC policymakers to meditate upon the possible future of the new Middle East. His vision includes an independent Kurdistan, an Iran shrunken to its ethnically Persian constituency, a string of Shia secessions in what used to be Syria, Iraq and Lebanon, and even a quasi-independence for the unruly Sinai peninsula, which the Egyptian state finds difficult to dominate. ‘Since 9/11,’ observes Goldberg, ‘America’s interventions in the region—and especially in Iraq—have exacerbated the tensions there, and have laid bare how artificial, and how tenuously constructed, the current map of the Middle East really is.’

‘After Iraq: A report from the new Middle East—and a glimpse of its possible future’ (Source).

Of course, part of the reason that the post-Ottoman successor states have survived, despite their ostensible artificiality, is that the international borders have been considered almost inviolable in the post-World War Two era. Borders are, after all, the defining essence of state sovereignty that forms the basis of international law. Numerous scholars have pointed out that rolling out the fully formed national-state across the world in the 19th and 20th century had the effect of preventing post-colonial successor states from adopting the same competitive strategies of evolutionary survival that had been implemented by the warlike polities of medieval Europe, the most successful of which naturally grew into ‘strong’ states such as France and Britain. Perhaps the problem with the Middle East, then, is not its instability, but the fact that international forces sustain that instability and prevent it from ever reaching the point of exhaustion?

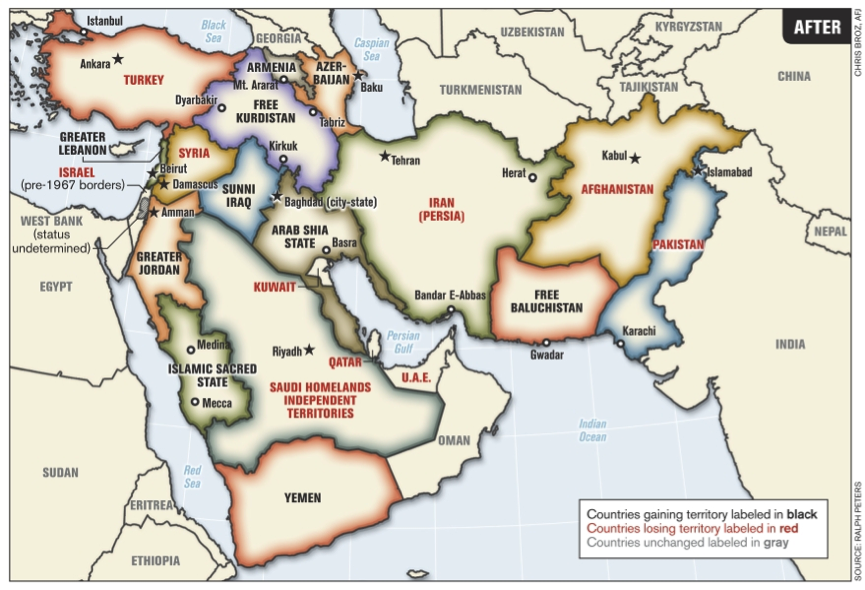

Naturally enough, this suggestion plays well with those whose political predispositions make them suspicious of international law, institutions, intervention, or any force that might constrain state interests, including the will of world superpowers. ‘The greatest taboo in striving to understand the region’s comprehensive failure isn’t Islam,’ argues Ralph Peters in the US Armed Forces Journal in 2006, ‘but the awful-but-sacrosanct international boundaries worshipped by our own diplomats.’ As for those who ‘refuse to “think the unthinkable”’ – that is, redrawing the map – Peters cautions them that ‘it pays to remember that boundaries have never stopped changing through the centuries….. many frontiers, from Congo through Kosovo to the Caucasus, are changing even now (as ambassadors and special representatives avert their eyes to study the shine on their wingtips).’

To replace the hallowed borders worshipped by diplomats, Peters proposes a new map of the Middle East that initially follows the familiar contours of an independent Kurdistan, a truncated ‘Persian’ Iran, and the secession of Shia Iraq. But it also extends Lebanon northwards to absorb the largely Alawi coastal mountains of Syria, enlarges Jordan into formerly Saudi territory to the south, and splits off the more commercial, cosmopolitan Hijaz and the two holy cities of Mecca and Medina (which become a ‘a sort of Muslim super-Vatican’) from the austere Saudi hinterland in the deep desert of the Arabian peninsula. Bahrain, meanwhile, is annexed by the Shia state that has Basra as its capital and encircles a Shia-locked Kuwait, ‘rimming much of the Persian Gulf,’ as Peters puts it. The West Bank limps on in Peters’ map, its status ominously ‘undetermined,’ while the ongoing siege of Gaza and its ensuing humanitarian crisis has apparently been solved by sliding it off the map into the Mediterranean Sea.

Middle East borders, as reimagined by Lt. Col. (ret.) Ralph Peters (2006) (Source).

Remapping the entire Middle East is an audaciously Herculean undertaking. As such, the authors of these programmes of border change and population transfer cannot fail to acknowledge that the speculative geography traced by their maps more properly echoes a Utopia, not the real world. Maps of various new Middle Easts are neither concrete policy proposals nor plans for action, but abstract thought-experiments the portentousness of which is so elephantine that not even the authors can entirely feign ignorance of the pachyderm in the room. Peters later confessed his surprise at the controversy provoked by his own contribution, which was, quite literally in his case, more freehand fantasy than serious policy design. ‘The art department gave me a blank map and I took a crayon and drew on it,’ said Peters. ‘After it came out, people started arguing on the Internet that this border should, in fact, be 50 miles this way, and that border 50 miles that way. But the width of the crayon itself was 200 miles.’

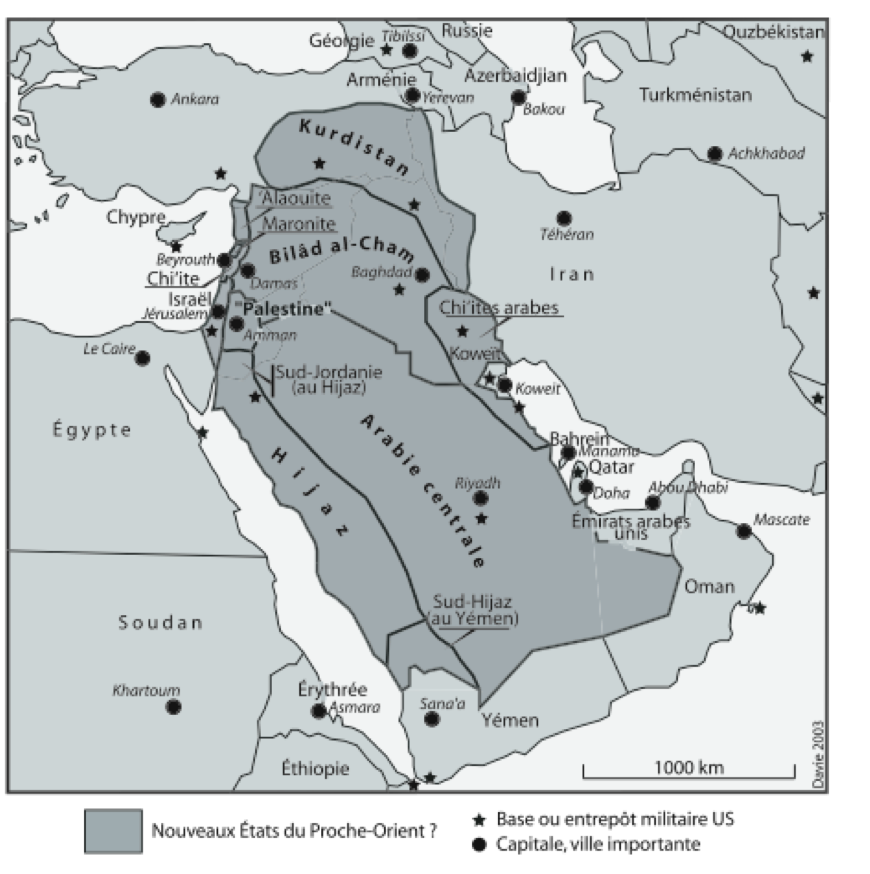

Such a schoolboy error would never have been made by a professionally trained geographer, of course. In a 2003 article published in Outre-Terre, a leading French journal for scholars of geopolitics, Michael F. Davie sought to explore the possible repercussions of the US-led invasion of Iraq for political stability across the region. Davie suggests that, after several years of US governorship, Iraq might become a tripartite federation of Kurds, Sunnis and Shia. This outcome, Davie hypothesized, would be more likely in the event of sectarian conflict that produced population transfers through incidents of ethnic cleansing. Syria might continue the slow trajectory towards liberalization that had gathered pace after the death of Hafiz al-Asad, though ideally the country might be run by a strongman who was less ‘intransigent and nationalist’ than his son Bashar. This new geopolitical climate might create a new space in which an independent Palestine might emerge, though Davie caveats that it would consist of a fragmented archipelago of micro-territories, not a contiguous national geography. Davie also envisages a more fundamental reshaping of the region’s borders, uniting Syria and Sunni Iraq in the country of ‘Bilad al-Sham’ (the Arabic term which refers to the ‘lands of Damascus,’ which historically covered Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, northern Jordan and parts of Iraq). The Hijaz once again becomes independent from Saudi Arabia, as does the ‘Southern Hijaz’ region of Asir. Underpinning Davie’s ‘hypotheses’ for the reconstitution of existing polities and the creation of new states are the assumptions of what he calls the realist paradigm of International Relations, based on the premise of continued unipolarity. The underlying assumption, in other words, is that US economic and strategic interests will act as both pregnancy planner and midwifeat the birth of the new regional order in the Middle East.

Les nouveaux Etats du Proche-Orient (Source).

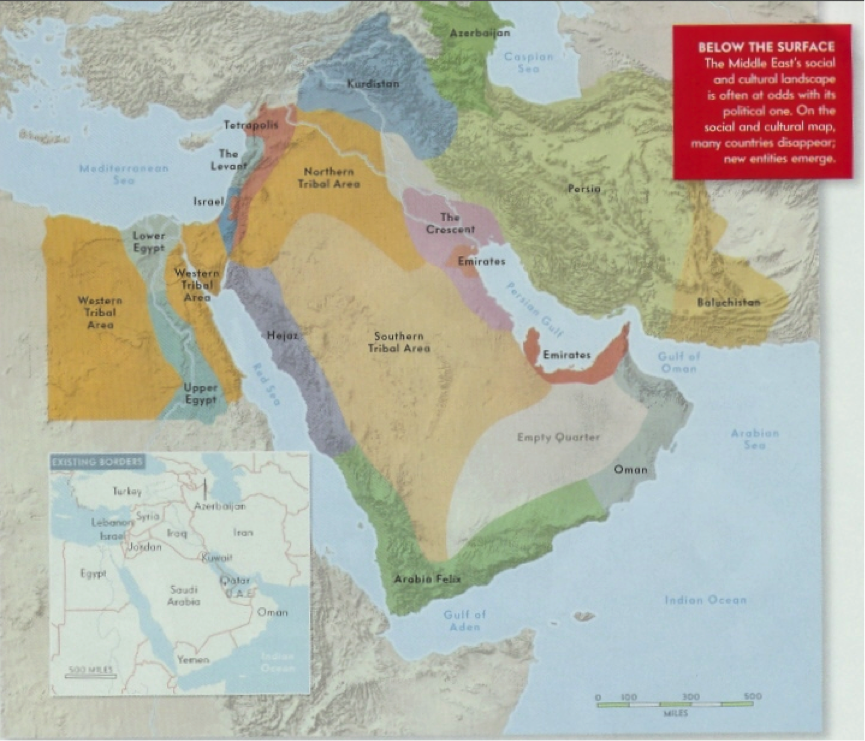

Our final exemplary case of remapping the region comes in the form of an exercise conducted by Vanity Fair in 2008, involving four US Middle East experts (Dennis Ross, David Fromkin, Kenneth Pollack, and Daniel Byman) who gathered ‘for part of a day in a room full of maps, seeking to identify regions that share certain bonds and commonalities – the Middle East’s underlying components.’ The quartet produced this roadmap:

What are the underlying contours of the modern Middle East? (Source).

Vanity Fair cautions that the experts’ map should not be mistaken for a policy proposal. ‘All the participants agreed that, particular negotiations here and there aside, we are stuck with the Middle East’s current borders.’ The map, we are told, simply shows the divergence of political and cultural borders in the region. ‘It is an explanatory tool: descriptive, not prescriptive.’ Furthermore, the map is not intended to represent US interests in the region. ‘The aim is not to define configurations as some outside “we” would like to see them, but rather to discern configurations that implicitly exist.’ Thus, we are delivered a novel assortment of cultural regions, ranging from the familiar (Kurdistan, the Emirates, Persia, Israel, Upper Egypt, Lower Egypt) to the fictitious (‘the Tetrapolis’), from the colourfully quaint (Arabia Felix) to the bland and nondescript: the Western Tribal Area, Northern Tribal Area, and Southern Tribal Area. (Presumably we should pity those cultural regions that are remarkable only for their correspondence to points of the compass.) Once again, the ‘real’ social unities of the Middle East are defined not by ideological or economic contiguity, but cultural continuity – whether tribal, ethnic, or merely urban – and flow contrarily to the neat geometric lines of modern state borders. This perceived discrepancy between map and reality creates a whole new space in which the unconstrained imagination can run free.

On the Cartographic Imagination:

Why is it that Western journalists and policymakers recurrently express such fascination with the notion of remapping the Middle East? As we have seen, even those who draw these maps admit they chart fantastical creations, stitched together from the disassembled body parts of real countries. Mythical entities such as Greater Jordan, Arabia Felix and the Tetrapolis act as stimulants to the political imagination: much like those incredible chimerae that illustrate the pages of medieval bestiaries, they are intended to provoke wonder and amazement, not to provide a field guide for encounters in the wild.

Given their singularly potent power to induce geopolitical fantasy, maps have long been the preferred opiate of occidental elites. From 1798 to 1801, Napoleon’s military conquest of Egypt was mirrored by a scientific conquest of scholarly savants, geographers and cartographers who produced the encyclopaedic Description de l’ Égypte: 23 massive volumes of maps, essays, and images that exhaustively charted every last expanse of Egyptian territory – or so it was claimed. In reality, the savants had barely even begun the mammoth task of conducting a cadastral survey of Egypt’s agricultural land – work that was not completed until 1907. Undaunted, these French shamen pushed the notion that the Description provided access to a higher esoteric realm of understanding in which would be granted a fuller, more complete and more perfect expression of Egypt’s reality than could be found in Egypt itself. After attaining this higher dimension by compiling the Description, the French could not only perceive the true shape of Egypt, but in their minds’ eye also transform the global reach of Napoleon’s Empire from spectacular delusion to palpable reality.

The hallucinatory effect of overlong meditation upon maps may in part have been popularized by colonial adventures in the Middle East, but the practice soon became widespread throughout the world. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, most notably, nationalist movements that demanded autonomy, self-rule, and independence couched their political vision in terms of their right to claim a sovereign space for their people alongside the sovereign spaces of other peoples. In later years, the vision of one people in one space successfully mobilized legitimate struggles against occupation and colonialism. But it also enabled darker imaginings of national purity, sometimes with murderous consequences, as the nation sought to ‘cleanse’ its territory of impure and alien elements. At its most extreme, the drive for the homogenization of a population within the space of a given state gave rise to genocidal impulses that reached their peak with both organized and spontaneous massacres and expulsions of ethnic and cultural minorities: the Holocaust of the Jews, the Killing Fields of the Khmer Rouge, the Akazu slaughter of Hutus and Tutsis in Rwanda, among many other instances. For good and for ill, the power of the map has induced across the world a collective dreamtime in which our political consciousness almost entirely exists within a realm defined by the cartography of nation-states. Deeply embedded in the this cartographic imagination is the notion that it should be natural that social divisions—whether along tribal, ethnic, religious or cultural lines—should correspond to spatial divisions that can be drawn straightforwardly on a map. From this perspective, Alawis, Sunnis, Shia, and Jews – and every other sect, ethnicity, or communal group, in theory – are all entitled to their own political sovereignties. This is the principle of one group, one state, in which identity and geography are – or, more dangerously, should be – essentially indistinguishable.

In this light, journalists who describe a remapped Middle East should not be understood as engineers carefully constructing prototypes for real political projects, but as daydreamers participating in a collective, map-induced trance. In this altered state of consciousness, redrawing the Middle East map is not the product of any individual political inspiration: those who draw these fantastical shapes are merely empty vessels, possessed by the power of the map, through which the cartographic imagination seeps into the corporeal world.

To propose that ‘natural states’ should replace the ‘artificial states’ created by the ‘Sykes-Picot’ settlement in the Middle East is (as hinted at by all six scare quotes) misconceived from the very beginning. Remapping the Middle East is no more than a fantasy concocted from a phantasm, an illusion distilled from the fragments of a half-remembered dream. The meaning of these fictive maps is, much like the meaning of a dream, hopelessly over-determined: they symbolize imperial self-delusion, social engineering, the will-to-power, political techno-fetishism, Utopian yearning, messianic promise – all this, and much more. The potency of the map is such that it stimulates the full scale, sensory range, and ambition of our political imagination. Yet, despite the promise of cartographic solutions to the political problems of the world, they simply prolong the life of the troublesome equation of identity and geography. It is this dangerous equivalence that needs to be unraveled, not the borders of Mr Sykes and Monsieur Picot. In order to overcome the problems of political geography, we must resist the pernicious temptations of the map-pushers and find a way to kick the habit of our cartographic imagination.

Daniel Neep is assistant professor in political science at the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, Georgetown University. He is the author of Occupying Syria under the French Mandate: Insurgency, Space, and State Formation (Cambridge University Press, 2012).