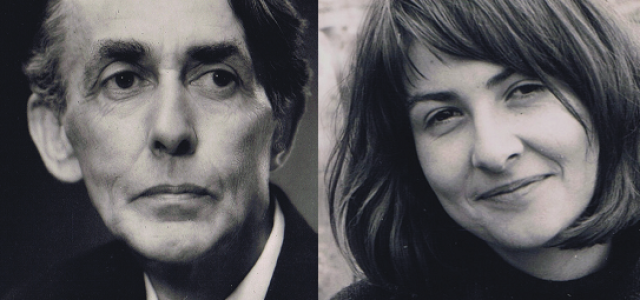

Photo: Richard Titmuss and Ann Oakley

Ann Oakley (Institute of Education, University of London)

Most of us would agree that our parents, families and childhoods are an important influence on what we end up doing and being. My new book, Father and Daughter, is about that influence, but with a particular slant; it takes my own work as a social scientist and that of my father, Richard Titmuss, who was also a social scientist and social policy analyst (he is regarded as having invented the subject of social policy), and examines their interconnections. But those links, with their moments of identification, resistance, and opposition, are also one way of telling the history of social science in the twentieth century.

Remembering home

The starting point for Father and Daughter was a revisit to my childhood home in West London when English Heritage erected a blue plaque to honour my father’s work. All houses have voices, said Virginia Woolf. They certainly embody memories. A particularly strong memory for me on going back to the house was of the years after 1950 when my father, a largely self-educated man from a rural family, became the first Professor of Social Administration at the London School of Economics. There he took over a department consisting mainly of senior women social work academics. Over the ensuing decade he transformed this into a department of social policy, staffed mainly by young men. It was not a smooth transformation – there were many arguments and both actual and threatened resignations. My father complained a great deal to my mother and me in the blue plaque house about the ‘difficult’ women he had to deal with. I believed everything he said at the time, as children do, but once I became an adult and acquired my own professional interest in the workings of gender I began to wonder what had really been going on.

The LSE Affair

Every story has different versions: the truth is a compound of all of them. I spent many months reading archives of the main protagonists in what commentators called ‘the LSE Affair’ – the struggle in Richard Titmuss’s department at LSE that resulted eventually in the closure of all the social work courses.(1) These archives included files my mother gave me: she died in 1987 fourteen years after my father, and had been an assiduous ‘pruner’ of his papers. What I uncovered in all this archival archaeology was a story about an international network of women social welfare activists and teachers who had been badly treated, both in the UK and elsewhere, by the academic establishment.

The ‘difficult’ women at LSE had been working closely with other women in the USA and Europe to promote social work as a profession. The ‘girls’ network’, as they called it, was driven by the two goals of practical welfare reform and a social science research base; ‘the girls’ saw a seamless relationship between research, activism, education and policy. All this was a considerable challenge to social science as it was developing in universities, especially from around 1950 on, when its own professionalization meant a break from activist politics and an emphasis on theory. This was what Mike Savage has called ‘a gentlemanly social science’.(2) The ‘difficult’ women at LSE had no place in it.

In putting together this part of the narrative of Father and Daughter, I also talked to some of the people who remembered what had happened at LSE in those traumatic years. They told me of the enormous respect they had for my father and his work, but also of what was widely perceived as a problem he had both with university administration and with women. I can sympathise hugely with the first, but of course not with the second. He and I clashed on the subject of women in the late 1960s, when I had discovered feminism, and had researched housework and the history and sociology of gender, and he had become something of an establishment figure, especially in the positions he adopted on student activism and on welfare benefits for women. His conservatism fired my radicalism – a quite normal generational reaction.

Filial memoirs and academic patriarchy

Memoirs by disgruntled sons and daughters of famous people form a particular genre, to which Father and Daughter does not belong – although I suspect some reviewers will think that it does. I am not a disgruntled daughter; on the contrary, as I hope I make clear in the book, I greatly admire my father’s work, and would not at all be the kind of social scientist I am without it. But there’s the rub: as a social scientist, my primary motive is always to understand the social context and processes that inform people’s lives.

The misogynies of academia – which more than linger today – are part of the context surrounding the LSE Affair. Institutional structures are not value-free, even (or especially) when they pretend to be so. Hidden in many of the archives I researched, often on scraps of weary paper, were notes about, and reactions to, decisions that effectively held women back, denying the evidence of their expertise and authority. Although some things have changed, there is a recognisable chain from these records to some of the problems in being taken seriously academic women have experienced much more recently.

Legendary lives

An important principle in my own social science is that the act of understanding cannot separate the public and the private: people’s public acts and accomplishments are supported by their private lives, by who they are as people. (Of course the public also impacts on the private, and we are much more used to seeing the connection this way round.) Richard Titmuss, the LSE Professor, was also Richard Titmuss, the family man; and both of these made up the man whose rise to such prominence from inauspicious beginnings is celebrated in a kind of socialist legend: defender of equality and ‘the welfare state’ ascends from the ashes of his own class oppression.

I came to understand, as I undertook the research for the book, something else about social context: that the stories we learn to tell about people’s lives are often at least partially made up of myths and legends. These suit us; they mesh with the spirit of the time. So in the case of Richard Titmuss, the myth of ‘difficult women’ merges with the legend of ‘the high priest of the welfare state’(3) to create a kind of methodological fog through which it becomes impossible to see how social science and social policy in the twentieth century so expertly managed to ‘forget’ the substantial intellectual and practical labours of women.

Auto/biography and life writing

The old distinction between ‘objective’ biographies and confessional autobiographies has fortunately now been dissolved by a more catholic attitude to different forms of life-writing. Father and Daughter is an inescapably odd mixture of my own life story with an attempt to tell a fuller version of my father’s, at the same time as having a go at the sociology and history of social science. I have always been fascinated by different ways of writing – hence my escapes into fiction, as well as other autobiographical and biographical work. All these tangle with essentially the same topics: identity, meaning, social context, the legacies of history.

What do I want people to take away from Father and Daughter? I think a certain scepticism about legends, a willingness to be open to other interpretations: a fascination – some of the fascination I have felt – with buried histories. There are also multiple lessons about archives, about looking after them, and about public accessibility. One of the most joyful moments for me in the research I did for Father and Daughter was a visit to the Bedfordshire and Luton Archives where I discovered a mound of dusty papers recording the struggles of my grandfather, a man I never knew, in contesting the enforced removal of some of his farming land in a government move to provide farms for ex-servicemen after the first World War. Through a carefully preserved verbatim transcript of the court proceedings, I was able to gain an impression of what kind of man this was. What happened to him shaped Richard Titmuss’s chances in life – a curtailed education, an impoverished move to London; and it fuelled his passion for the statistics of inequality. His passion and my own, different from but also the same as his, are part of the story of social science and policy in the twentieth century.

Notes:

(1) D Donnison, ‘Taking Decisions in a University’, in D Donnison, V Chapman, M Meacher, A Sears & K Urwin, Social Policy and Administration Revisited (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1965), 253-85.

(2) M Savage, Identities and Social Change in Britain since 1940: The politics of method (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 93.

(3) AH Halsey, ‘Titmuss, Richard Morris (1907–1973)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 204).

Ann Oakley is Professor of Sociology and Social Policy and Founding Director of the Social Science Research Unit at the Institute of Education, University of London. She has worked in social research for almost fifty years and has published widely on gender, domestic work, health care, and the history of social science and methodology. Her latest book, Father and Daughter: Gender, patriarchy, gender and social science, examines the interconnections between her own work, and that of her father, Richard Titmuss, as a case-study in the development of twentieth century social science.