Ras Cos Tafari, Sister Stella Headley, Ras Shango Baku, Dr Robbie Shilliam, Ras Rai I, Sister Addishiwot Asfawosen

What does the British public know about RasTafari? Perhaps they might recognise the colours – red, gold and green – although they might mistake them for the Jamaican flag instead of the royal Ethiopian standard. The word “stoned” might come to mind, implying the use of a “drug” called Marijuana, which to members of the faith is a holy herb and used as part of a sacramental rite. No doubt they would be able to sing a line from Bob Marley’s “Three Little Birds”, while probably being less familiar with the singer’s more political Pan-African oriented songs such as “Africa Unite”.

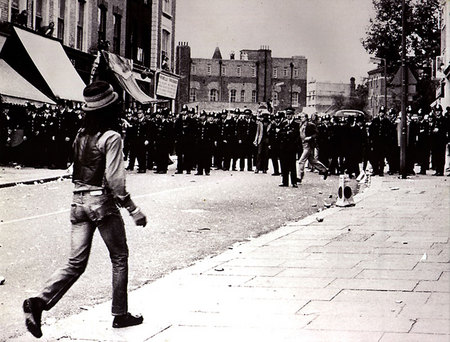

Older members of the public might also think of the iconic cover of The Clash’s Black Market Clash, where a lone “dread” (Don Letts) confronts a line of police. In this respect, they would be referencing a time before the current Muslim scare when young Black men with dreadlocks occupied the position of public enemy number one as muggers, drug dealers, fanatics and rioters.

It would not be unfair to say that in Britain RasTafari has largely been apprehended as either a colourful curiosity or a corrosive cult. Yet it is neither of these. At its root, RasTafari is a movement of Pan-African redemption, confronting the inequities forged in the days of slavery and colonialism that continue to reverberate across physical, mental and spiritual dimensions. RasTafari take their name from the title that the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie I held as crown prince. Ras is a rank, meaning “head”; Tafari can be glossed from the Amharic as “a person who inspires awe”.

It would not be unfair to say that in Britain RasTafari has largely been apprehended as either a colourful curiosity or a corrosive cult. Yet it is neither of these. At its root, RasTafari is a movement of Pan-African redemption, confronting the inequities forged in the days of slavery and colonialism that continue to reverberate across physical, mental and spiritual dimensions. RasTafari take their name from the title that the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie I held as crown prince. Ras is a rank, meaning “head”; Tafari can be glossed from the Amharic as “a person who inspires awe”.

As a movement, RasTafari finds its compass and energy store in a faith (some would call it a “livity”) that centres upon the divine nature of Selassie I and his consort, Empress Menen – the Ethiopian Alpha and Omega. Many observers of the RasTafari movement are captivated by its aesthetics and music. Some will sympathise with the RasTafari ethos. Most, though, will be confused by the overwhelming love demonstrated for Selassie I, which they will interpret as evidence of fanaticism, cultism or the result of harmless recreational smoke.

In fact, RasTafari carefully utilise diverse and complex theological and cosmological traditions to “sight up” the nature of Selassie I’s divinity, expertly weaving together Biblical prophesies, doctrines of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and indigenous cosmologies that arrived with those Africans trafficked illegally across the oceans to work as chattel on plantations.

Hence, for RasTafari, the fundamental challenges posed to humanity in the twentieth century and beyond are manifested in the life, experiences and utterances of Selassie I with Empress Menen. But you do not have to rely on our testimony alone. For there was a time when even the British public loved RasTafari. Step back into this history with us, because we want you to know us better.

Rally around the Red, Gold and Green

It is July 1935 and Mussolini has amassed Italian troops on the frontiers of Ethiopia. After manufacturing a border “incident” the previous year, Mussolini wants to reverse the historic defeat suffered by Italy from the armies of Ethiopian emperor Menelik II at Adwa in 1896. Like all reputable European imperialists, he is determined to stake out his own place in the sun – the horn of Africa. And he has already taken Eritrea and Italian Somaliland.

The Italian aggression is met by offers of diplomatic engagement by the new Ethiopian emperor, Haile Selassie I, in an effort to avoid bloodshed and maintain peace. But while Selassie I has negotiated Ethiopia’s full membership of the League of Nations, it is unclear to what extent this predominantly European organization will defend an African polity against one of its own.

Neither is it clear at this point that the British government will definitively seek to uphold Ethiopia’s sovereignty. However, the aggression of an imperialist and fascist European power against a predominantly Christian African polity creates a quite unique common front of protest in Britain formed of socialists, anti-imperialists, feminists, pacifists and Christians alike. What is more, this common front spans the white populous and resident/visiting Black peoples from Britain’s African and Caribbean colonies.

On July 26th a public protest in support of Ethiopia is convened at Essex Hall in London’s Strand by Sylvia Pankhurst (Women’s Committee against War and Fascism), George Brown (League of Coloured Peoples), Reginald Reynolds (No More War movement) and Reginald Bridgeman (League against Imperialism). Around the same time a statement by the National Council of Labour is made to the British government insisting that “no foreign loans should be made available to facilitate the slaughter of Africans for the glory of a new fascist empire”.

Meanwhile, Jomo Kenyatta, future leader of independent Kenya, has convened the International African Friends of Abyssinia in order to “assist by all means in the territorial integrity and political independence of Abyssinia”. And on the 15th August they hold a well attended rally at Trafalgar Square that attracts black and white supporters, as depicted below.

Meeting in Trafalgar Square, Auugust 15th 1935

Meeting in Trafalgar Square, Auugust 15th 1935

On the 3rd October Italy invade Ethiopia from their Eritrean base. In Britain, support for Ethiopia mushrooms with the creation of associations such as the Friends of Abyssinia League of Service, the International Brotherhood of Ethiopia, and the Abyssinian Association. Numerous fund raising activities from individuals and groups are undertaken in all the major cities from Newcastle to Belfast and across the country including Honiton,in Devon.

The British public follow events in Ethiopia carefully. They mourn at news of the murder of resistance leader Ras Desta Damtew (Selassie I’s son-in-law), and they denounce the massacre by Italian fascists of 30,000 Ethiopians in February 1937. Some will continue to agitate in support of Ethiopia up to the outbreak of World War Two. Witness, for example, the Welsh Tinplate Trade Workers writing to Selassie I in May 1938 after the British government have formally acknowledged Italy’s sovereignty over Ethiopia:

…we send to you and the people of Abyssinia our deep sympathy in this their hour of betrayal, and we deeply deplore the action of so many of our fellow Christians in giving silence acquiescence to this immoral act. [It is] the act of a small governing clique in our county and does not represent either the wishes or the character of the great mass of the British people.

On 5th June 1936, Selassie I, some of his family, and a small retinue arrive at Waterloo station in London. Mandated by his Crown Council to escape the occupying Italian forces in order to pursue justice abroad, Selassie I has chosen Britain as his base of operations. He has had to arrive officially incognito as the British government have decided to maintain cordial relations with Italy.

Unofficially, however, Selassie I arrives as sovereign of Ethiopia and prince of peace. One month prior, Sylvia Pankhurst publishes the first edition of New Times and Ethiopia News, an anti-fascist and anti-imperialist newspaper devoted to the Ethiopian cause. Pankhurst’s newspaper reports the arrival of Selassie I at Waterloo. Remember: this is London 1935, not Kingston, Jamaica, 1970s:

A huge crowd thronged and mustered outside. The Friends of Abyssinia made the welcome colourful by great scarlet banners of welcome and flags and armlets in the Ethiopian colours. Members of the public also spontaneously displayed home-made banners, hat-bands, button holes and badges.

And it is not just white people who make up the crowd:

An address was also presented by the Pan African Federation, and there were present on the platform representatives of the International Friends of Ethiopia, the Gold Coast Aborigines Protection Society, the Negro Welfare Association, the British Guiana Association, the League of Coloured Peoples, the Universal Negro Improvement Association, the Gold Coast Students Association, the Somalia Society, the Colonial Seamen’s Association and the Kikuyu Association of Kenya.

Some of the people from these organisations, included CLR James, George Padmore, Jomo Kenyatta and Amy Ashwood Garvey, ex-wife and co-creator with Marcus Garvey of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, subsequently form the International African Services Bureau. The Bureau stated that “With the assistance of English friends”, it sought to “cooperate with peace loving and democratic and working-class forces” in order to support “the demands of Africans and other colonial peoples for democratic rights, civil liberties and self-determination”. They attributed the need for such a Bureau directly to the Italian invasion of Ethiopia.

And so from 1935 to the start of the Second World War, diverse elements of the British public rally around the flag of Ethiopia – the red gold and green. They consider Ethiopia to be the testing ground of international morality and global justice. They even believe that the fate of humanity – European as well as African – pivots on this moment of truth.

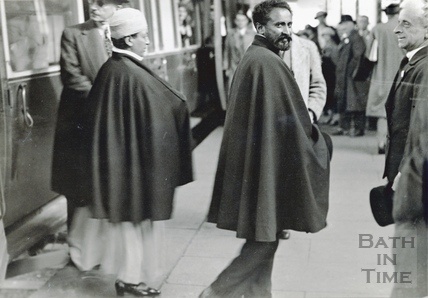

Haile Selassie I and Empress Menen arrive in Bath, August 1936

Haile Selassie I and Empress Menen arrive in Bath, August 1936

Bath well-wishers greet Haile Selassie I and Princess Tsahai

Bath well-wishers greet Haile Selassie I and Princess Tsahai

Mystic Revelations

Shortly after his arrival in Britain, Selassie I travels to Geneva, and on June 20th 1936 addresses the League of Nations – the first head of state to do so directly. The appeal is politely ignored by the member states of the League. In Britain only Pankhurst’s newspaper prints Selassie I’s speech in full. For in his appeal to the League for support against the Italian occupation, Selassie I warns that inaction will ensure that what the fascists are doing to Ethiopia will ultimately be visited upon European peoples. It is a prescient moment.

Here is an eye-witness report of that moment; note: this is not written by a dreadlocked member of the RasTafari faith, but by John Hilton, a white English writer for the New Statesman:

Yesterday I listened to the speech of the Negus. I have never heard or seen anything quite so impressive as his manner of delivering it. He did not move a finger or a muscle of his face. It was that kind of ultimate self-control and self-restraint that comes of great suffering nobly borne. I had an odd feeling that he was unreal; as if he belonged to a dream world, as if he were a sort of shadow. He seemed to radiate a spiritual quality in the light of which that congregation of go-getters didn’t quite know where they were or what they ought to do. When the Italian journalists yelled at him he stood there quite still, quite unmoved, very king-like. The way he left the assembly after having listened to the interpretation of his speech was so full of ancient dignity and inner strength and repose, that for two pins I could believe souls are in transit and his has been journeying for ages and ages. I had the feeling, and I’ve still got it, that his very presence there before the assembly was an Event, and one that in some queer way will tell.

Upon his return, Selassie I and the royal family move to the ancient spa town of Bath and on 21st September 1936 take up residence at Fairfield House. The city of Bath embraces their new Ethiopian neighbours.Those residents who were children when Selassie I first came to Bath remember the emperor along similar lines to that of the New Statesman reporter. Dr Shawn Sobers has collected some of these voices in his documentary, Footsteps of the Emperor. Having been greeted by Selassie I as a child, one resident remembers a “sense of being in the presence of someone who was more than a man … a sense of truth, honesty, perfection”.

Indeed, Selassie I seems to carry the same authority with him as he sojourns across Britain. One newspaper reports on a visit by the emperor to Molesey Lock swimming pool in the Thames, subsequent to visiting the Egyptian delegation at Hampton Court: “He was recognized immediately, and the 1500 bathers gave ‘three cheers for the Emperor’ and cried ‘Hail, Selassie!’ which has become the popular retort to fascist slogans”.

Thus, in the years leading up to the Second World War, Selassie I has become a notable personality on the British stage. Some members of the public glean from his presence something more than just flesh and bones: he seems to carry the weight of global injustice but also the hope of a brighter future. To some, he has even pierced the veil between the manifest and sublime world in his pursuit of global justice.

When Britain forgot RasTafari

In 1954 Selassie I returns to Britain thank the public for their support during the Italian war and gifts Fairfield House to the people of Bath to be used as a respite for the elderly. Meanwhile, Pankhurst’s remarkable newspaper, New Times and Ethiopia News, is still running. In 1956 the Custos of St. James parish, Francis M. Kerr-Jarrett, writes to the Governor of colonial Jamaica requesting that the newspaper be banned from the island. Kerr-Jarrett is worried that groups of poor Black people have been reading the paper avidly.

Following the ethos of their namesake, these RasTafari greet all in the name of “peace and love”, warn of spiritual death to all oppressors, black and white, and agitate to repatriate to Ethiopia, their homeland. Disturbed by the fact that the brethren and sistren have cast aside the image of a white Jesus, Kerr-Jarrett writes a letter to Governor Hugh Mackintosh Foot in which he suggests that the Colonial Office in London might obtain “a refutation of the (RasTafari’s) claim that Haile Selassie is God.”

RasTafari at the entrance to Fairfield House. RasTafari, in conjunction with members of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and residents of Bath are currently involved in the safekeeping and use of the property

RasTafari at the entrance to Fairfield House. RasTafari, in conjunction with members of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and residents of Bath are currently involved in the safekeeping and use of the property

In the 1960s RasTafari are appearing in Brixton market. But by this time, in contrast to the reception barely six years earlier for Selassie I, the Observer newspaper is disparagingly reporting that RasTafari “object to washing” and “elect to live in holes and hovels on the outskirts of Kingston.” The Observer doubts that Selassie I has even heard of these lunatics. However, this first generation of RasTafari in Britain have come specifically to develop closer diplomatic relations with Ethiopia in order to facilitate their repatriation. They also wish to encourage a more pragmatic and political sensibility amongst their brethren and sistren in Jamaica who are suffering oppression. For in April 1963, barely a year after independence, the Jamaican police forces have killed, wounded and arrested scores of RasTafari in Coral Gardens.

In 1972 Selassie I returns once more, in an informal capacity, to advise Prime Minister Ted Heath on the situation in Rhodesia and to encourage Britain to support the liberation struggles that rage on the continent. By the mid 1970s a new generation of RasTafari emerge, born, bred and schooled in British cities. Marginalised by a euro-centric educational system, alienated from mainstream society, ill-fitted for the labour market, they reject what they see as the submissive attitudes and ‘Christian’ values of their parents. Although perceived as delinquents, these youth have also caught the spirit of liberation. And they find their inspiration in a philosophy of Black pride and resistance that is transmitted through their Caribbean heritage and borne on the airwaves by the music of RasTafari.

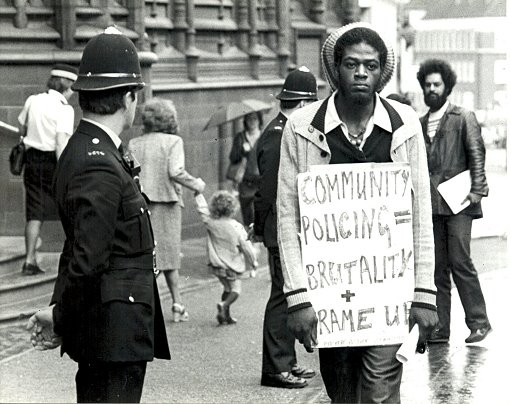

London march against police brutality in Jamaica, 1978.

London march against police brutality in Jamaica, 1978.

Protesting racist policing outside Birmingham law court, 1980.

Protesting racist policing outside Birmingham law court, 1980.

Simmering institutional and visceral racism directed at Britain’s Black communities leads to outbreaks of rioting in 1981. Subsequently, Lord Scarman is tasked with leading a public inquiry into these insurrections. Organizations such as Rasta International hold meetings with Scarman who, in order to gauge the pulse of the community, has been reading literature on RasTafari. Perhaps Scarman is old enough to remember a different time when the British public sided with, not against, RasTafari and the cause that the name and title represents: African redemption for the sake of humanity.

To Remember and Repair

In 1935 the British public embraced Selassie I and the Ethiopian cause. The majority viewed Selassie I as the prince of peace. Some even saw more than a man as they rallied round the red gold and green, the colours that they associated with global justice. What is more, some even supported Britain’s Black African colonial subjects as they also rallied round the Ethiopian flag in pursuit of independence and dignity. We who are called by the name RasTafari are only pursuing the same project. Why only see us, then, as a colourful curiosity or a corrosive cult? Has Britain forgotten that it once loved RasTafari?

In truth, such forgetting has taken place on a global level, and in Ethiopia as well. Recently, Dr Desta Meghoo has sought to repair the global memory by putting together an exhibition at the National Museum of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, entitled RasTafari: The Majesty and the Movement. Opening for one month on May 25th – Africa Liberation Day – the exhibit has attracted over 7600 visitors. The exhibition seeks to educate visitors on the deep and intimate links between the life of the Majesty – Haile Selassie I alongside Empress Menen – and the Movement in his name.

A mobile part of the exhibition has also visited Shashemene, a town approximately four and a half hours drive south of Addis Ababa. Shashemene holds great importance to RasTafari as the site where in 1948 Selassie I gifted 500 acres of crown land for settlement by the African Diaspora in the West for their support during the Italy/Ethiopia war.

Ethiopian youth at a reasoning session on RasTafari at the Ethiopian World Federation, Shashemene, 28/5/14

Ethiopian youth at a reasoning session on RasTafari at the Ethiopian World Federation, Shashemene, 28/5/14

Empress Zaditu from the Sick Be Nourished Project dispensing medical supplies to the people of Shashemene, 29/5/14

Empress Zaditu from the Sick Be Nourished Project dispensing medical supplies to the people of Shashemene, 29/5/14

As the UK team in this project, we were tasked with retrieving the British connections between the Majesty and the Movement. Next year will be the 80th anniversary of the invasion of Ethiopia by Italy. We hope that you who are resident in Britain will come and see some of the exhibits that we will be displaying in public fora to remember this moment. We hope that you might come to know your own history a little better, and in so doing, will come to know us as something more than a colourful curiosity or a corrosive cult.

Sources:

Norman Adams, The Rastafari Movement in England: A Historical Report (London: GWA works, 2002) ISBN 0-9543025-0-8

New Times and Ethiopia News, British Library Newspaper Collection

National Archives, Kew (Colonial Office records)

People’s Museum Archives, Manchester

Sister Addishiwot Asfawosen is an Ethiopian fashion designer, photographer and jeweller; Robbie Shilliam is senior lecturer in International Relations at Queen Mary University of London; Sister Stella Headley is an educationalist and founder of Shashamene Youth Creation; Ras Shango Baku is a Rastafari journalist, author and activist and editor of Rastafari Speaks and Thunder, voice of the Nyahbinghi National Council UK; Ras Cos Tafari is Director of Majestic Radio and a musician in his own right. His CD releases include Rally ‘Round and The Crowning; Ras Rai I is a musician, sound engineer and producer of film documentaries.