Jan Eichhorn, University of Edinburgh

The 18 September 2014 will be an important date not simply because of the important vote on Scotland’s constitutional future. It will also mark the first time that 16- and 17-year olds will have been allowed to vote at the national level in Scotland. This is of significance for two reasons: First, some people criticised the extension of the franchise because younger people could not be trusted to cast a meaningful vote, as they would simply vote like their parents – if they cared at all in the first place and were informed enough to cast a vote. These critics have become a little quieter in the debate, but that does not lower the rationale for engaging in some more depth with this age group, even when it only makes up about 3% of the electorate.

Second, the experience from this referendum is likely to influence further discussions about the lowering of the voting age to 16 more generally, both in Holyrood and Westminster elections (regardless of the outcome of the vote). We have a chance, therefore, to engage in depth with a group of young people that could become the centre of much speculation when discussions about the voting age will be held.

Methodological background

In order to assess how young people form their views on the referendum and whether they are merely a copy of their parents and other adults or distinct and informed themselves we can make use of the survey carried out by our research team in April and May 2013. (1) This data is the only complex probability sampling survey carried out on the under-18 year olds extending to all those eligible to vote in the 2014 referendum, thus including young people aged 14 at the date of the survey (who would mostly be 16 by 18 September 2014). The total sample included 1,018 14-17 year olds residing in Scotland and was carried out by random digit dialling via telephone. One parent was interviewed briefly after being asked for ethical consent before talking to the young person. (2)

Copycats or uninterested?

One of the most common criticisms of lowering the voting age is that young people do not form their own political views, but merely follow those of their parents. We had the chance indicatively to check this claim with regard to the referendum as we also asked the parent on the phone about their voting intention. Only about 56% of young people had the same voting intention as the parent we interviewed – while 44% indicated a different one. Young people do not seem to be a mere carbon copy of their parents when it comes to their decision making.

Is that surprising though? Not really if we look at a few further figures: While we may have been used to assuming that party identification was passed on from one generation to another we find that traditional parties do not offer much orientation to young people. While a large majority of adults still declares an affinity to some political party (3), 57% of young people indicate that they do not feel close to any political party at all. The results of the process of decreasing party alignment over the last couple of decades can clearly be seen in our sample of young people. Traditional identifiers play a less significant role in the formation of their political views.

This however does not mean that these young people are disengaged at all. Indeed, levels of political interest are very similar between young people and adults. As Figure 1 shows, levels of political interest amongst the 14-17 year olds in the survey of young people are very similar to those of adults in the Scottish Social Attitudes Survey. While the latter does not contain a middle category exact comparisons for each degree of interest respectively are not possible, but nevertheless we can clearly see that young people do not show lower levels of interest at all. This also translates into voting intention: Only 13% of young people said that they were very or rather unlikely to vote. The high levels of expected turnout seem to also apply to the newly enfranchised voters.

Figure 1: Political interest of young people compared to adults in %

(comparing 14-17 year olds to all adults in the 2012 Scottish Social Attitudes Survey)

Complexity in attitude formation

Taking this into account we cannot dismiss non-alignment with parties and differences to parental voting intention as mere consequences of disinterest or political disengagement per se. What then influences young people in their attitude formation?

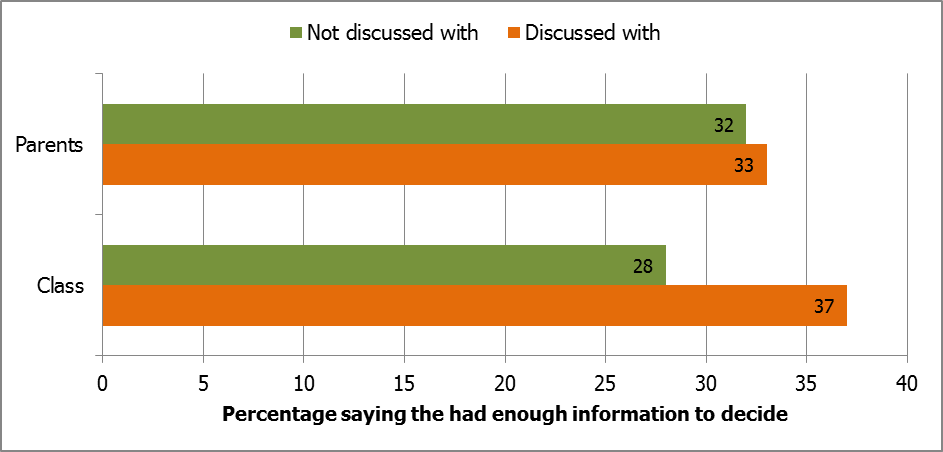

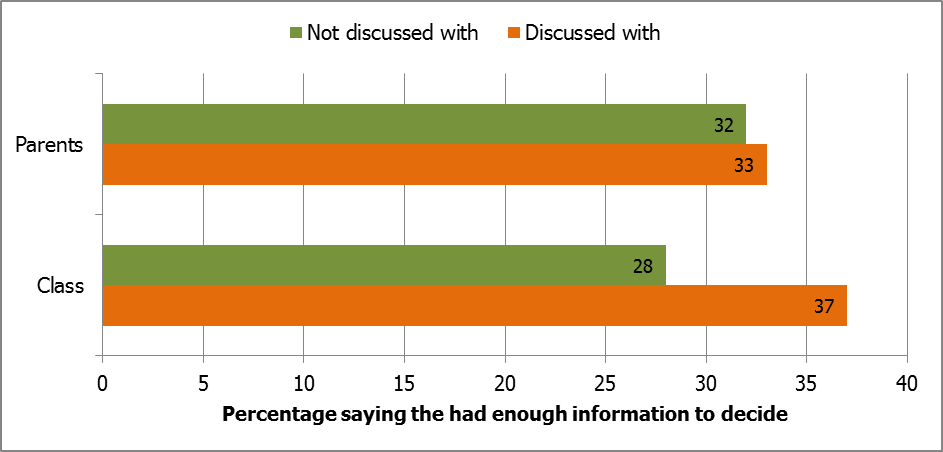

We can actually explain why parents may not be so influential in shaping the views of young people on the independence referendum. Those young people who had discussed the referendum with their parents (56%) did not feel any more informed about it than their peers who had not talked to their parents. Both groups had nearly the same likelihood of saying that they had enough information to make a decision in the referendum (at 33% and 32% respectively). Probably unsurprisingly by now talking to parents had no overall biasing effect on young people with regard to the referendum voting intention. 23% of those who had talked to their parents wanted to vote ‘yes’ while 24% of those who had not talked to them indicated an intention to vote ‘no’.

Figure 2: Influence of talking to parents and in class about the referendum on perceived knowledge

A different picture emerged however, when we looked at the effect of having discussed the referendum in school. Indeed, those who had already discussed the referendum in the classroom were more likely to say they had enough information (37%) than those who did not (28%). The difference was statistically significant and robust even when controlling for other factors in a logistic regression model. (4) Similarly, the results for talking to parents (i.e. the non-differences) were robust in such models. However, importantly, discussing the referendum in school did not bias young people to vote one way or another. While those who had talked about the issue in class were slightly less likely to vote ‘yes’ (27%) than those who had not discussed it (20%), this difference proved to not be robust and became insignificant when using the control variables in our logistic regression model. (5)

Young people seem to distinguish between different sources of information. While discussions in school appear to affect the self-perceived confidence in the knowledge they hold, parents do not have the same effect. However, parents do play a role in the likelihood of voting. Those 14-17 year olds who had discussed the referendum with their parents were significantly more likely to vote than those who did not – an effect that could not be observed robustly for discussions in class. While discussions in school appear to affect the perceptions relating to knowledge formation, talking to parents affects evaluations related to traditional political socialisation – such as voting as a norm in the first place.

Conclusion

Claims about the inability of 16-17 year olds to vote ‘properly’ in the referendum are not backed up by empirical evidence from this survey. While there are some uninterested young people, the proportions are very similar to those we find for adults. The dealignment from political parties is not a reflection of political disengagement per se, but an indication that young people seek different identifiers than those provided by traditional actors. Only slightly more than half of the young people held the same voting intention as one of their parents and while parents influence the likelihood of young people voting, talking to parents about the referendum does not bias young people in their voting intention. Young people also distinguish between sources of information – discussions with parents do not lead to greater confidence in political knowledge, whereas discussions in school do, indicating that not all sources are treated with equal weighting by the young people it seems. They clearly are not simple copies of their parents or anyone else for this matter, but form their views through complex mechanisms that warrant further study to understand similarities and differences in comparison to adults – rather than these being merely asserted.

__

Notes

(1) The research team consists of Dr Jan Eichhorn, Prof Lindsay Paterson, Prof John MacInnes and Dr Michael Rosie (all University of Edinburgh, School of Social and Political Science). The project is funded through the ESRC’s Future of the UK and Scotland Programme and carried out under the umbrella of the Applied Quantitative Methods Network (AQMeN).

(2) Through this we were able to identify one bias in our sample: Households in which at least one parent held a higher education degree were overrepresented. The differences however, did not bias our results extensively (2-3 percentage points on any given question). Nevertheless, we weighted to the expected distribution of parental education (using data from the 2012 Scottish Social Attitudes Survey) so that results were adjusted accordingly for this bias (2). All results reported here are weighted.The weighting was done to match the distribution expected based on the highest educational qualifications of respondents from the 2012 Scottish Social Attitudes Survey aged 30 or above who were living in a household with at least one child aged 14-17.

(3) Eichhorn, J. 2013. Will 16 and 17 year olds make a difference in the referendum? ScotCen Social Research Briefing. Available at:

(4) Control variables included: sex, age, national identity, whether they have taken Modern Studies as a subject, parental education, whether they feel close to any political party and political interest.

(5) Details for these analyses can be obtained here: Eichhorn, J., Hübner, C., Heyer, A. 2014. Who influences the formation of political attitudes and decisions in young people? Evidence from the referendum on Scottish independence. d|part briefing. Available at:

Jan Eichhorn is a Chancellor’s Fellow in Social Policy at the University of Edinburgh’s School of Social and Political Science.