Debbie Samaniego and Felix Mantz

On June 3, Logan, a town in Cache Valley approximately one hour north of Salt Lake City (Utah), was identified as the number one COVID-19 hotspot in the USA. Cache Valley has a population of approximately 128,000 residents and is also home to a large number of food and animal industries, including slaughterhouses, as well as packing and processing plants for dairy and meat.

Many of these factories have stayed open during the COVID-19 pandemic as they were deemed essential industries by the US government. This has resulted in the current rise of COVID-19 cases in the county and exposed the entanglement of multiple systems of power and exploitation in the valley. These include, among others, racial capitalism, the migrant and citizenship regime of the US settler colony, and anthropocentrism and speciesism.

One of the companies operating in the valley that has received a lot of attention since the first weeks of June is JBS Beef – Hyrum, which is part of JBS USA (which itself is owned by the Brazilian JBS S.A.), the largest meat processing company in the world. Despite recent mass-testing at the Hyrum facility revealing that 28% of JBS workers tested positive for COVID-19, the plant was not closed and continues to operate.

The racial dimensions of the coronavirus pandemic are extreme. In Cache Valley, these racial dimensions expose the underlying precarious economic conditions that force people of color to work in dangerous and unhealthy environments, which are now amplified by the potential exposures to COVID-19. Specifically, a significant number of Cache Valley’s JBS workers (and workers employed by the food industry across the USA more generally) are Latinx and/or immigrants.

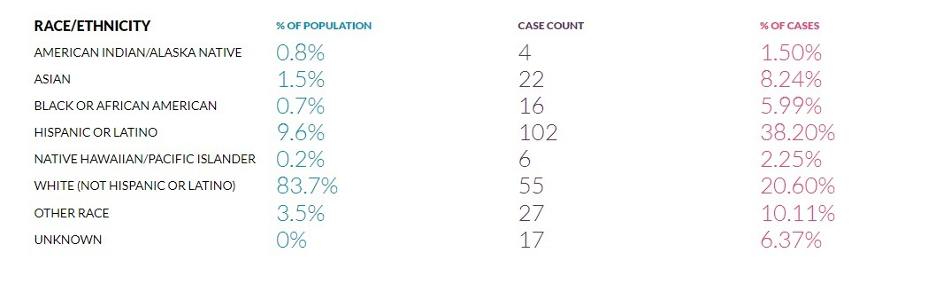

According to a local refugee organization, 80% of Cache Valley’s refugees work at JBS where entry-level positions do not require fluency in English. It is these brown and black workers who have been most affected by the pandemic. While constituting only 10.9% of Cache Valley’s population, Hispanics/Latinx account for 38.2% of total COVID-19 cases.

In contrast, non-Hispanic Whites constitute only 20.6% of COVID-19 cases even though they make up 83% of the population (the same patterns can be observed at the state level). Interestingly, the data recording the racial and ethnic distribution of coronavirus cases in Cache Valley was recently taken down from the county’s webpage, and only the state-wide statistics remain. We took a screenshot of the statistics from June 3, one day before it was deleted.

According to workers in the plant, within JBS, the racial divide is replicated as well. Most people of color work on the production lines in close proximity to other human workers and animals, while whites are disproportionately concentrated in management positions. Workers’ reports suggest that this divide is institutionalized through racist and settler-colonial regulations such as the requirement to have “good English skills” if one wants to apply for a management position.

On June 9, the COVID-19 outbreak in JBS led workers to refuse to work and organize a demonstration in Logan (a rare sight), protesting risky working conditions, safety concerns and the alleged holding back of information by JBS on the true number of COVID-19 cases. These are not the only problematic practices of JBS. While the company’s official statement is that sick people should stay home, workers have reported that they were asked to work regardless of their health condition wherever possible.

Moreover, while employees are given the choice to not work if they are concerned about their health, for many going to work is not a “choice” but an economic imperative (many live paycheck-to-paycheck). On top of all this, a few weeks before JBS was catapulted into the local spotlight, the company proudly posted picture promos praising their health and safety measures with hashtags like #YouFeedAmerica (What workers feed who to what kind of Americans?).

In Cache Valley, the pandemic is clearly exposing a wide array of entangled systems of oppression. The first is racial capitalism, which reserves the exploitative, labour-intensive work (of humans and non-humans) in the animal industrial complex, with long (day and night) shifts and low-pay, to primarily brown Latinx and disproportionately black African refugees. Their working conditions in this industry in particular are hidden from view as it is extremely difficult to access animal processing plants or slaughterhouses, saving not only the welfare and condition of animals but also that of human workers from public scrutiny. Out of sight, out of mind.

The workers in the plant are considered expendable and undeserving of protection or isolation (long-standing racist imaginaries of the lower risk to non-white bodies when exposed to toxins come to mind as well). They must continue to feed America, as if they themselves are not Americans in need of food. Here racial capitalism interlinks with the migrant and citizenship regime of the US settler colony on indigenous (in particular Shoshone) lands.

The racialization of Latinx peoples in the US, which enables their exploitation by capitalism, is based on the hegemony of the US settler state, which deems non-white peoples from Meso- and South America as not-belonging, non-citizens. These regimes of exclusion and racialization are also extended to African refugees.

Finally, in this pandemic where images of cleared up cities have provoked misguided and potentially fascist exclamations of “Humans are the Virus,” it is clear that in Cache Valley the industrial-scale exploitation of animals must go on! COVID-19 clearly has not resulted in a serious re-examination of the relationship of Euro-modernity and its mode of civilization to the more-than-human, to Mother Earth. In a time of escalating global ecological crises where such a re-thinking is indispensable, JBS (and Cache Valley more broadly) is a prime example of how the current capitalist, modern, anti-black, and anti-red/brown settler-colonial regime holds on to anthropocentrism, speciesism and its toxic/unhealthy relationship to the more-than-human.

All these entangled processes force us to ask the same question which has (once again) been posed by the global protest movement following the murder of George Floyd: whose lives matter, whose lives are considered valuable and whose are undeserving or expendable? Power, in its multiple horrifically-creative and perverted ways, once again demonstrates the lives that do not matter: those of non-human beings, the undocumented, workers, non-whites, and those who find themselves in their intersections.

The demonstrations in Cache Valley are risky, powerful, and important, but it is doubtful that they will lead to serious change in the short-term. Deeper mobilization, organizing, and connecting (with other ongoing struggles in the Valley and beyond) would be necessary. It is equally necessary to identify, uncover, and uproot the multiple systems of exploitation and oppression in their entanglements and the multi-faced forms of violence they generate due to this pandemic.

What are the connections between anti-black and anti-brown racism, capitalism, and anthropocentrism? How do these interlink with the settler colony, its anti-Indigeneity and migration, border, and citizenship regimes? What role does hetero-patriarchy and sexism play? What struggles are underway, what alternatives proposed and how can we support them?

Debbie Samaniego is a PhD researcher in the Department of International Relations at the University of Sussex. Her research interests include decolonial theory, migration and citizenship regimes, indigeneity, and settler colonial studies. Felix Mantz is a PhD researcher in the School of Politics and International Relations at Queen Mary University of London. His main research interests include anti/de-colonial theories, indigeneity, radical political ecology, as well as resistance and alternatives to Euro-modernity and its civilizational model.

Image Credit: “The Utah Theatre” by jimmywayne is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.