Georgina L Jones, Kirsty M Budds, Francesca Taylor, and Crispin Jenkinson

2021 will mark the twenty-year anniversary since the Endometriosis Health Profile-30 (EHP-30) was first published. Its development provided the first psychometrically established, patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) designed to specifically evaluate the impact of endometriosis from the woman’s perspective. In this piece, we provide an overview of where the EHP questionnaire has been used around the world since its development, and reflect upon what the gaps might tell us.

Endometriosis and quality of life measurement

Developed using methodology from the social sciences, PROMs are questionnaires designed to provide a means of measuring the impact of illness, and its associated treatments, or other types of intervention, from the patient’s perspective. This valuable information not only provides the opportunity for the patient to express the impact of the illness upon his/her well-being but it can also aid in their clinical management by enabling healthcare professionals to monitor patients’ progress and consequently influence decisions about treatment.

PROMs have many other important roles in evaluative research. This particularly applies to the interpretation of randomised controlled data where their use can provide additional information on the benefits of the medical therapies or interventions to aid clinical decision-making. They can also be used in audits and surveys to capture information on the health needs of populations beyond the traditional mortality and socio-demographic data, which are not specific enough to inform decision-makers about the allocation of resources.

Endometriosis is one of the most common chronic gynaecological conditions affecting women. Although the prevalence is difficult to determine, it is estimated as high as 10%. It is usually defined as the presence of endometrial tissue, which starts growing in locations outside the uterus. It typically affects women of reproductive age, i.e. from the onset of menstruation to the menopause, and it usually regresses after the menopause.

Symptoms include chronic pelvic pain, painful periods (dysmenorrhoea), pain on defaecation, pain on intercourse (dyspareunia) and sub-fertility. But other symptoms such as fatigue have also been reported. There is no cure for endometriosis and treatment options are limited, with varying degrees of success. Those available focus on symptom control, including pain relief, hormonal therapy, surgery, and, where relevant, fertility treatment. Consequently, endometriosis imposes heavy demands on women and the medical profession and it can result in substantial costs to healthcare systems in the treatment and management of the condition.

The EHP-30

In recognition of the value to be gained from measuring quality of life and the accounts of suffering reported by some women living with the condition, the EHP-30 was developed. Originally produced in the English language, it consists of a core instrument, with five scale scores covering: Pain; Control and powerlessness; Social support; Emotional well-being, and Self-image. In addition, there are six additional modules covering areas of health status that may not affect every endometriosis sufferer.

These are optional and can be chosen by users (in any combination) to assess the areas of quality of life that may be particularly relevant as required. The six separate modules cover: Work; Relationship with child/children; Sexual relationship; Feelings about the medical profession; Feelings about treatment, and Feelings about infertility. EHP-5, a shorter version of the EHP-30 was also developed by the team.

Where are the gaps in the use of the EHP measures?

Prior to the development of the EHPs, the impact of endometriosis and associated interventions upon women’s quality of life were little understood. For example, a review of the literature, published in 2002, identified that only three medical studies and one surgical study had assessed the outcomes of these treatments from the woman’s perspective, all of which had been carried out in developed countries (OECD).

The question is, how have the EHP measures been used by the International community over the last twenty years and how might its use have advanced our understanding of the impact of the condition as self-reported by women? We have started to explore this by examining what translations of the EHPs have been undertaken and reviewing what licences have been granted for its use in research. All the licences are held by Oxford Innovations (a spin out company from the University of Oxford). The EHP measures are free to use for all non-commercial research and publicly funded organisations, but are associated with a fee for commercial entities.

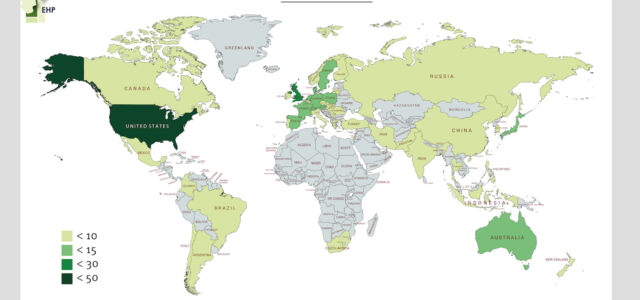

Since its development, the EHP-30 has been translated into 36 languages and licences are currently held in 49 different countries. Out of the 37 OECD countries, 33 hold licences for the EHP. Figure 1 displays geographical data, showing the countries where the EHP licences are held. The map also shows where the measurement of quality of life for women with endometriosis is lacking. Africa is most notable here, as well as parts of Central and South East Asia, the Middle East and Central and South America.

What might the gaps in the use of the EHPs tell us?

Many healthcare systems have been accused of failing women living with endometriosis. Time to diagnosis can take many years and there continues to be accounts from women who feel their symptoms have been neglected. In the meantime, many women report enduring years of suffering from chronic, debilitating pain and/or infertility without adequate access to care and support. However, it has been suggested that these experiences may be even more compounded for women from BAME groups and those living in poverty.

In 2012, the WHO published their report: ‘Addressing the Challenge of Women’s Health in Africa’. One of the key findings expressed was the urgent need for better data: “because women bear a large burden of disease during the reproductive period, monitoring their health outcomes at this phase, and evaluating the quality of care provided to them is especially important.” The lack of quality of life research in endometriosis using the EHP could be explained by a less developed infrastructure, chaotic healthcare systems and conflict, all of which will undoubtedly play a role in some of the aforementioned countries.

Other authors have been more critical, suggesting the absence of endometriosis data and research in less economically developed countries is indicative of an “empire of endometriosis”. Such an absence may be linked to a widely held belief that endometriosis rarely affects African women. However, those who dispute this, point to data which illustrates that women of African descent within North America and Europe suffer with endometriosis and suggest that instead of being absent, experiences of endometriosis among this group of women are ‘neglected’ or ‘forgotten’ (Annan et al., 2019).

Elsewhere, it is suggested that the low prevalence of endometriosis among African women may be explained by factors such as a lack of awareness of the condition; limited access to facilities to aid diagnosis; and a lack of training among health professionals to diagnose the condition (Kyama et al., 2007). There is also some belief that African women may be protected against endometriosis since many begin having children at a young age and have more of them, thus spending more of their reproductive years pregnant and limiting their exposure to retrograde menstruation, a risk factor for endometriosis.

However, whilst we are mindful not to perpetuate the historical notion that endometriosis is only a condition that affects ‘career women’, Kyama et al (2007) suggest, the roles of some women in Africa are changing such that they are spending more time in education, beginning families later and having fewer children, which could leave increasing numbers of women at risk of developing endometriosis.

The suggestion that there may be an ’empire of endometriosis’ has also been echoed recently in other media reports, such as in The Guardian, a UK broadsheet. In 2015 they published an article entitled ‘Endometriosis: the hidden suffering of millions of women’ in which, Dr Reid (an Australian Gynaecologist), was quoted as saying “There are a lot of countries that don’t even recognise its [endometriosis] existence, especially the Middle Eastern countries”. A review of the map of EHP licences shows an absence of its use in countries such as Saudi Arabia, Oman and The United Arab Emirates, as well as the Central Asian countries of Kazakhstan, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan to name a few.

Implications for the future

Endometriosis can undoubtedly have a devastating impact upon the quality of life of many women who suffer from the condition. From our review of where EHP licences have been taken out over the last twenty years, there are large parts of the world where it has not been used.

The reasons for this are unclear. However, without self-report patient data, such as that collected through the EHPs, improvements to patient care and treatment are unlikely to progress. Our observations of the use of the EHPs are preliminary and the team are currently involved in undertaking a thorough literature review to explore this further – especially given that there are other measures which can be used to collect this quality of life information. However, the picture emerging perhaps speaks of a need to raise awareness of endometriosis in developing countries, and to identify more ways to measure its impact upon the lives of all women worldwide.

Georgina Jones is a Professor of Health Psychology at Leeds Beckett University. Her research uses both quantitative and qualitative research methods and focuses on quality of life measurement, psychometrics, decision-making and questionnaire development, with a special focus on women’s health. Kirsty Budds is a critical social and health psychologist and qualitative researcher at Leeds Beckett University. Her main research interests are in the topics of women’s reproductive health and parenting. Francesca Taylor is a PhD student and research assistant at Leeds Beckett University. She uses qualitative methods and participatory and feminist approaches to research issues of gender, sexuality and reproductive health. Crispin Jenkinson is Professor of Health Services Research, Director of the Health Services Research Unit, and a Senior Research Fellow of Harris Manchester College at the University of Oxford.

Image Credit: Copyright held by Clinical Outcomes: Oxford University Innovations, Ltd.