Reva Yunus

In December 2019, the Indian government passed the Citizenship Amendment Act 2019 (CAA) which has been criticized nationally and internationally for using religion as a basis for citizenship; it also excludes groups that have been targets of brutal persecution, like the Rohingyas from Myanmar, Ahmadiyas from Pakistan and Tamils from Sri Lanka. The greatest concern with the Act is that operating in tandem with the National Register of Citizens (NRC), it can strip millions of Indian Muslims of their citizenship.

What seems to have come as a surprise to the government and people of India, was the relentless spate of protests organized without any central or party leadership across the country. Several were led by Muslim women who were themselves first time protesters. However, since the women, especially the poorer ones often had no access to childcare facilities their children accompanied them and sometimes the entire family would be present at the protest site.

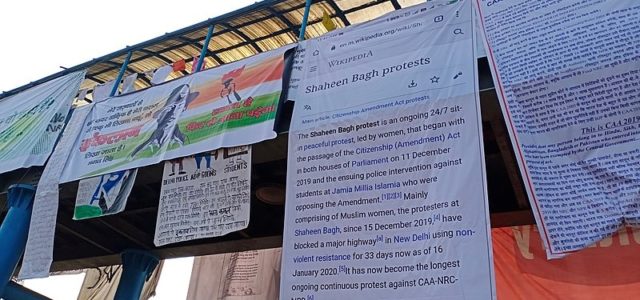

The most famous of these sites has been the Shaheen Bagh in Delhi. There were stories of women joining protests days after giving birth, accompanied by the infants. One of these Shaheen Bagh women, Nazia, tragically lost her four-month-old son, Mohammad Jahaan, due to a cold and congestion on 30 January, 2020.

Nazia, and her husband Arif, used to attend the protests with their three children and lived in ‘a makeshift house made of plastic sheets’ close to Shaheen Bagh. Some ten days later the Supreme Court of India, taking suo moto cognisance of Jahaan’s death, sent a notice to Delhi government to ask why children and infants were allowed at the protest site. In taking this action the court had turned a letter addressed to the Chief Justice of India from a twelve year-old girl, Zen Sadavarte from Mumbai into a formal public interest litigation (PIL).

A few days before Jahaan’s death, the National Commission for the Protection of Children’s Rights (NCPCR) had asked for children present at the protest to be provided counselling as they were being exposed to ‘traumatic’ events and ‘false propaganda’. Later in March, the NCPCR ‘sought a report’ from the local district magistrate in view of the COVID-19 pandemic and a recent ban on large gatherings in the capital.

It would seem that institutions of the Indian state have sought to appropriate the narrative of child rights and use it to control protest(er)s. The hegemonic discourse of child rights that underpins policy in developing contexts like India derives from a modernist Eurocentric understanding of ‘childhood’ and tends to position as ‘deficient’ any reality that ‘deviates’ from it (Raman 2000). The Eurocentric ideal child is protected from the grim realities of the adult world and involved only in school work or play.

Ignoring the genealogy of the notion of childhood and child rights, dominant (inter)national discourses of development circulate ahistorical accounts of ‘childhood’ which elide children’s locations in socioeconomic matrices. This, in turn, enables a discourse of the need to ‘rescue’ children that constantly pits the rights of the child against the interests of the community or family (Raman 2000).

Scholars have pointed out that hegemonic narratives of child rights have often ‘essentialized and sentimentalized’ children’s suffering instead of grappling with the structural causes of this suffering (Sircar and Dutta 2011). Similarly, (inter)national discourses of education reform seek to abstract the question of poor children’s education from its historically specific contexts (Sriprakash 2016). In the present case, isolating Jahaan’s death from the systematic disenfranchisement of Muslim community, allows the state to continue persecuting the community while appearing to uphold rights of an individual (Muslim) child.

In recognizing Zen Sadavarte’s letter as a PIL the Supreme Court also foregrounds the question of child rights perceived as universal, rather than that of citizenship which is a site of contestation and discrimination. Thus, its action also obscures the Indian state’s unequal relationship with different groups of children. The Hindu, middle class, urban child is much closer to the figure of the ideal child than working class or poor Muslim children; in listening to the former the court not only acts as if she can legitimately speak for all other children but also appears to be listening to and having concern for, all children. However, the court has not taken into account the concerns of mothers protesting the CAA; the women are worried about both the potential trauma of their children being caught in citizenship battles and children’s questions regarding the relentless anti-Muslim rhetoric in Indian media.

The way various institutions have zeroed in on the children present at Shaheen Bagh as objects of intervention and ‘rescue’ belies their usual indifference to the multiple kinds of injustice and deprivation faced routinely by large sections of Indian children. These are the Other of the ideal child in the Indian context: whether it is the children of urban informal workers unable to access housing, food or healthcare, Kashmiri children who are pellet victims, or rural Dalit children starving to death because of issues arising from mandatory biometric authentication required to access welfare benefits. Activists and academics have pointed out that it is the marginalised sections of children (rural, poor, Muslim, Adivasi, non-dominant caste) who will also suffer more because of the ‘bureaucratic paper monster’ that the NRC-CAA exercise is bound to be.

Indeed, a version of the NRC exercise has already been carried out for India’s north-eastern state of Assam; while the Assam case has a substantially different history and logic, it raises important questions that are relevant to development of a registry of citizens anywhere in India. The Assam NRC excluded 6% of its population, 1.9 million people – including Hindus – from the final published list. After its publication many have been sent to detention centres, families broken up, children separated from parents, and complications have arisen from children being included while parents aren’t and vice versa.

However, neither the Supreme Court nor the NCPCR has shown any great concern for the wellbeing of these children. These institutions have also remained silent witnesses to long treks undertaken by children and families along highways without food, toilet facilities or shelter from harsh weather, in the wake of a COVID-19 induced lock down announced by the Modi government with little preparation or foresight.

These arguments are not meant to trivialize Jahaan’s death, rather to underscore the significance of the political context in which he died and the way the Indian state has chosen to respond. It is important to ask: would the state have been concerned if Jahaan had died in a detention camp? What rights would children like Jahaan have if one or both of their parents are declared non-citizens? How will they survive if their families have to spend all their resources on proving every family member’s citizenship as many have already had to do? How are children’s rights defined during or after such tests of citizenship and what will the state do to safeguard these?

Asking these questions is a way for us to recognize that child rights cannot be abstracted from their socio-political contexts and rights and concerns of families and communities; while the patriarchal or bourgeois family is no benign institution viewing the child only as an individual also does not necessarily offer solutions. Postcolonial scholarship on childhood indicates that it may be far more fruitful to hold on to the tension between the modernist view of the child as an individual and the child member of families and communities. This is especially important in view of historical inequalities among children from different socioeconomic groups and the role of the state in perpetuating these inequalities, as the colonial and post-independence state in India has done, for example, in matters of work and education (Balagopalan 2014).

Child rights activist Shantha Sinha has also problematized the NCPCR’s logic and actions and argued that the state has not shown similar ‘concern’ in other cases of children being ‘traumatized’ (children questioned by the police multiple times for participation in an anti-CAA school play) or exposed to ‘propaganda’ (children involved in re-enacting the 1992 demolition of the Babri Masjid in a school).

On the one hand, development discourses focused on international aid and child rights have historically refused to engage with the fallout of liberalization in third world countries. On the other, there has been a consolidation of the authoritarian state in post-liberalization India. These developments demand that academics and activists working with children and/or researching childhood must also stay alert to the appropriation and misuse of the discourse of child rights, especially, by the state; and ways in which children may become objects or instruments of control.

References:

Balagopalan, S., 2014. Inhabiting ‘childhood’: children, labour and schooling in postcolonial India. Springer.

Raman V (2000) Politics of childhood: perspectives from the South. Economic and Political Weekly 35(46): 4055-4064.

Sircar, O. and Dutta, D., 2011. Beyond compassion: Children of sex workers in Kolkata’s Sonagachi. Childhood, 18(3), pp.333-349.

Sriprakash A (2016) Modernity and multiple childhoods: interrogating the education of the rural poor in global India. In Hopkins L and Sriprakash A (eds.) The ‘Poor Child’: The Cultural Politics of Education, Development and Childhood. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 151-167.

Reva Yunus is an ICSSR (Indian Council of Social Science Research) postdoctoral fellow at the School of Education, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, India. She has a PhD in Sociology from the University of Warwick, UK. Her research interests include sociology of education, economic informalization and urban informality and childhood studies.

Image Credit: Wikimedia