Anna Barker and Andrew Smith

One of the more surprising aspects of the COVID-19 lockdown in the UK has been the political and media attention dedicated to parks and green spaces. There seems to be a new awareness of the importance of urban green spaces for wellbeing, particularly for citizens who do not have access to private gardens. Some people have flouted social distancing rules, provoking threats that parks might be closed if national guidance is not followed, but the government is now urging local authorities to keep them open. At the beginning of World Parks Week (25 April – 3 May), the government announced a further 340 parks and green spaces had reopened.

As academics interested in parks, we welcome this renewed appreciation and visibility. It places a spotlight on the precarious position of parks following a decade of budget cuts, their lack of legal protection and status as a discretionary rather than statutory service. The impact of disinvestment was acknowledged by a parliamentary inquiry in 2016-17 which warned that Britain’s “parks are at a tipping point, and failure to match their value and the contribution they make with the resources they need to be sustained could have severe consequences.” Three years on, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced politicians to acknowledge the benefits of parks and to think about how public access might be sustained. The pandemic has changed the ways parks are used and managed and in this article we assess the significance of these changes and discuss their likely legacies. The coronavirus crisis will have lasting effects but we also suggest that the current situation provides a glimpse of the kinds of parks we may see in the future.

Recent research on what parks might become in the future identified six possible images of tomorrow’s green spaces. However, futures are unpredictable; they constitute the unfolding of a multiplicity of factors, only some of which may be knowable. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic for parks is – to use an analogy popularised by Taleb – a ‘black swan’; a highly improbable or unexpected event that has long-term ramifications and socially transformative consequences.

In the UK, unlike in some other countries, public parks have generally remained open during the period of lockdown to allow people to take daily exercise. Yet there are huge variations in the availability and quality of parks across England. This unequal access has been accentuated during the coronavirus crisis, as people have been required to ‘stay local’. This is a particular problem in London where more than half of households do not live within the recommended maximum distance (400m) from a park. While we know that most people’s experience of nature is close to home, local parks are not always preferred by a significant minority of park users. Nearly a third of Leeds parks users, for instance, travel beyond their immediate locality to access the attributes and facilities of another park. A lack of facilities, accessibility needs, not enough things to do, insufficient size and anti-social behaviour are all factors that can all push people to travel to non-local parks. Therefore, as the UK lockdown began, it was unsurprising that people gravitated to popular, well-resourced parks, making it difficult to maintain safe distances between users.

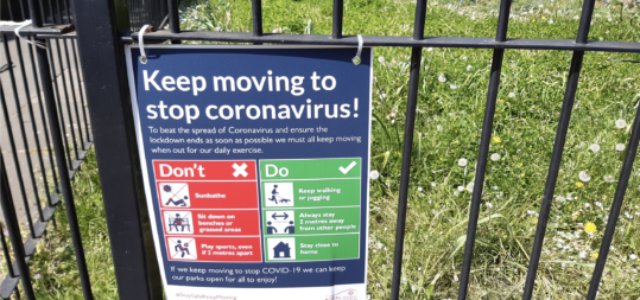

If you have been able to access a park over the past few weeks, you will know a series of measures have been implemented to promote physical distancing. Signs and stencils have been installed to encourage users to stay two metres apart, benches have been removed or taped up and some parks have banned cycling to give people more space. Playgrounds, cafés and other popular areas that can be easily cordoned off have been closed. Arguably it is these facilities that distinguish parks from other green spaces, so UK citizens are having to get used to a new reality of pared down parks.

If you have been able to access a park over the past few weeks, you will know a series of measures have been implemented to promote physical distancing. Signs and stencils have been installed to encourage users to stay two metres apart, benches have been removed or taped up and some parks have banned cycling to give people more space. Playgrounds, cafés and other popular areas that can be easily cordoned off have been closed. Arguably it is these facilities that distinguish parks from other green spaces, so UK citizens are having to get used to a new reality of pared down parks.

Despite their Victorian origins as rather stiff and formal settings, contemporary parks have been reinvented as more loosely regulated sociable places and it has been very difficult for some users to adapt to new COVID-19 rules which prohibit picnics, BBQs, team sports and exercise classes. More controversially, some solitary pursuits are discouraged, including sitting and sunbathing; turning spaces which have long been used as places to relax and dwell into agitated spaces of continuous movement, circulation and flow. The logic of ‘pedestrianism’ that governs the city’s streets is now infiltrating parks.

New regulations are enforced by a mixture of old-fashioned visible policing and social media shaming. There have been more police patrols in parks since the lockdown, but authorities are also relying on self-regulation and pressure exerted by other park users to enforce ambiguous behavioural codes. To make the job of managing parks easier and cheaper, and to discourage groups from gathering in the evenings, some local authorities have restricted opening hours. Restrictions have also extended to the ways people access parks: cars and car parking are now banned in many cities including Glasgow.

To allow urban green spaces to stay open, our parks have had to change. But what are the long-term legacies of the crisis for parks; will any of these changes be retained once the lockdown is over; and can the current situation be regarded as an experiment to test different ways of managing parks?

The main legacy is likely to be a serious crisis in park funding. Local authorities were already struggling to resource adequately parks following a decade of austerity, and there is likely to be even less money available in the next few years. Around 30% of park funding comes from commercial sources – mainly from car parking charges, concessions, events and other activities that have been curtailed. Local authorities may need to ramp up commercial activity in parks once the crisis is over, something which is likely to be opposed by many Friends groups.

Hopefully, there may be some positive legacies too. In the context of closures to pubs, museums, cinemas, libraries and so forth, visiting parks has become a more essential, displacement activity. Many people have adopted new exercise routines away from indoor gyms and have discovered green spaces near to where they live. Some of these new behaviours may be retained. The new visibility of parks may increase use, and the lack of commercial installations (e.g. cafés, attractions, events and other organised fun) may make people more aware of the simple joys of nature. Before the pandemic, there were proposals to ban cars and improve security in some parks and the current crisis is a useful experiment to test different new management approaches. Some of these positive legacies suggest the crisis might provide a blueprint for a more utopian vision of city parks that are car free, more ecologically focused and well used for outdoor exercise. It may lead to a revaluing of these vital public assets and remind us that parks must be accessible to all and that we should avoid over-commercialisation.

However, it is also possible to think of parks in the pandemic in a more negative light: as a glimpse of dystopian future. We now have parks without social interactions which cater for individuals who keep their distance and do their socialising online. The capacity to lock down popular areas, or limit opening hours, may be a foretaste of parks where access is more restricted. We have got used to parks being more heavily policed, with (mis)behaviour publicly exposed and this, alongside the glut of new rules, provides a glimpse of more ordered, authoritarian parks. Compared with other public spaces where hanging around is discouraged, parks are one of the few urban places where it is possible to dwell and loiter. However, the pandemic has highlighted that parks might become places where ‘moving people on’ is the overriding design and management logic. Everyone is grateful that parks have remained open, but the crisis has also given us a foretaste of the sort of parks we don’t want.

Ultimately, the crisis has reminded everyone about the social value of accessible green space. The government minister responsible for parks and green spaces from 2018-19 was an up and coming politician called Rishi Sunak. When this crisis is over, public parks are going to need the support of Mr Sunak in his new role as Chancellor of the Exchequer to ensure that people will still be able to enjoy accessible and convivial parks long into the future. With physical inactivity the fourth largest cause of mortality in England, and increasing pressure on mental health services, this investment will also help to protect the NHS and save lives, even when people no longer have to stay at home.

Dr. Anna Barker is a Lecturer in the School of Law at the University of Leeds @Barker1Anna Dr. Andrew Smith is a Reader in the School of Architecture + Cities at the University of Westminster @andrewsmithwest

This article is based on a series of online discussions involving the authors and several other UK academics, including Nicola Dempsey (University of Sheffield), Jill Dickinson and Adele Doran (both Sheffield Hallam University), Helen Hoyle (University of the West of England) and Meredith Whitten (London School of Economics).