Nick Stevenson

Recently I have been writing a historical article about George Orwell. While doing so I have come across a lot of material about how the world he envisaged hasn’t arrived, and that his predictions were misplaced. It is also widely presumed that the dystopian present is more like the narcotised society of Huxley than the big state of Orwell – that control emerges more through seduction than through ideological manipulation and top down control.

I have never been convinced of this view. So when it came to describing neoliberalism as the world of consumer freedoms and slimmed down state this seemed seriously mistaken. In fact, as many sociologists have pointed out, neoliberalism is more commonly reliant upon the big state than many presume. This can be seen in the intense regulation of borders, lives of the poor and of course the prison building programme to contain those who do not fit into the consumerist dream.

Indeed, the media manipulation evident in making the case for the war in Iraq, the legitimating of the use of torture and New Labour’s use of ASBOs began to dent this picture. After the market crash of 2008, the everyday cruelty of the state has become more apparent in terms of detention centres for migrants, far reaching welfare benefit cuts and schools who were seemingly willing to shrug off their responsibilities to the most vulnerable in pursuit of good exam results.

This has all happened without most of the population giving up on the image of the British as being fair-minded, tolerant and offering people a safety net through the hard times. But still this was a world seemingly far removed from the one feared by Orwell at the mid-point of the twentieth century. We still had freedom of thought, expression and assembly despite the dominance of the millionaire press and the state broadcaster being overly geared to the views of celebrities, politicians and the wealthy. However, over the past few weeks, this picture has begun to shift.

If Orwell was always more significant than many people seemed prepared to admit, this is now more obvious than ever. Here we need to remember that ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’ was always intended to be a warning and not read as a set of predictions. Orwell, at the end of his life and dying from tuberculosis, had seen up close the cruel indifference of the state during the hungry 1930s and its capacity for war, destruction and manipulation during the Spanish civil war and the Second World War. This was a period that cared little for the conscience of the individual, which was largely seen as expendable by violent and authoritarian states.

If there was hope then it lay with ‘the proles’, whose ordinary humanity Orwell felt had not been corrupted by the lust for state power. However, Orwell saw many of his fellow intellectuals as willing to self-police in order to serve an ideology like state communism or free-market capitalism. Just at the point when they were needed to raise critical questions and pose ideas of justice, Orwell’s contemporaries had become victims of the dominant ideologies of the time.

For Orwell, hope lay not so much in political elites but in the capacity of ordinary people to face the truth and struggle for a better world. He of course recognised that they may also become corrupted, but there was more hope to be found in ordinary feelings of love and fraternity than the power politics that dominated the Europe of the 1930s and 1940s. Orwell’s socialism was a matter of patriotism, equality, intellectual freedom and the ordinary decency of the working-class population so despised by members of the elite.

Since the arrival of Covid-19 and the mass shut down of British society it is now hard to think of someone more in tune with our times. Each day I take a walk and usually bump into someone I know. I have noticed mostly what people have wanted to say to me is, ‘let’s hope something positive comes out of all this!’. This is all being fanned by a lot of well-intentioned articles in the liberal press on how the world may have changed for the better once the crisis is over. Indeed, the news media is full of stories of everyday hospitality and self-help as ordinary people seek to make it through the lock down. This is in sharp contrast to other stories of a mounting crisis and of a sense of doom as the death toll mounts daily and the numbers of people who have become seriously ill begins to rise. It is not surprising that most people wish to be cheerful at a time like this, evoking a wartime spirit of people clubbing together for the common good.

This would all have been recognisable by Orwell. The everyday kindness of ordinary people and their capacity to show strength, courage and humanity in a crisis is something much of his writing testifies. Whether Orwell was tramping the streets, fighting in Spain or pondering war-time Britain he continually reminds us that most people are basically decent. Different rules apply, however, to the powerful state.

One of the most troubling aspects of this crisis is the way the government is not being held to account. The Labour Party and the Trade Union Council seem to have accepted that we are in a national crisis and this is not the time to be too critical. Under ‘wartime’ conditions it is a time instead for us all pull together, stay cheerful and try and help each other. After all, the daily briefing from the British state and the scientific experts offer us the basic information we need to stay safe. Yet the suspension of democracy and criticism is deeply dangerous.

We already know about how the government has changed its strategy on ‘herd immunity’, failed to respond to the crisis quickly enough and has not provided adequate protection for NHS staff. If we add to this, the workers employed in less than safe conditions unable to adequately socially distance we might become even more concerned. Finally, the focus on the ‘heroic’ efforts of the working-class population barely conceals a system that disallows a genuinely living wage. Indeed, if the working-class at some point in the future decide to join together to press for improvements in their material conditions they will soon revert back to being the villains of the piece. Nor does it acknowledge the numbers of people whose lives could have been made better through the introduction of a basic income.

Of course, Orwell the pragmatic socialist would have quickly recognised why this road was not taken. Imagine if this measure had been introduced and been experienced by the mass population as genuinely popular. This would then have been much more difficult to remove in the future. Much easier to bail out companies and offer some help to stave off public disorder.

The silencing of criticism, dire warnings and feel good stories are all tried and tested strategies used to manipulate the public. Indeed, the idea we are ‘at war’ with a virus generates a level of fear and panic in the population making them much easier to control. Of course, the law has not been suspended, but there are now lots of stories about the police ‘over-reaching’ and interfering in daily life more generally We might also caution that democratic meetings that could have taken place in public spaces can now only occur over the net. But here, of course, post-Edward Snowden, we all know about the state’s ability to keep its citizens under surveillance.

Orwell would have warned us about the world we could be entering into if we are not careful. Where criticism of the state is seen as unpatriotic and letting the side down, and people who are seen to be behaving less than ‘heroically’ are routinely denounced as selfish and greedy. I noticed how many people online were angry about the so called hoarding of food and essential supplies. Friends got in touch worried about the food supplies running low and the stress of trying to find the basics. Again Orwell’s common touch was required as perhaps this was a perfectly understandable response by people buying food they might need as they struggle to look after loved ones, and that reassurances by the state of a plentiful supply might not turn out to be true. The storm created around so called ‘panic buying’ is a useful strategy encouraging people to blame each other rather than those in authority for mishandling the crisis.

It is not that Orwell would have refused the sensible advice coming from the state, but would have cautioned about where this all might lead. That during a temporary suspension of our liberties we become more used to being directed by the state and its capacity for cruelty. Notable over the past few weeks is that the citizenry (by and large) accept being told what do and to think. Orwell would have reminded us that it is precisely during a national crisis that we need defend our freedom to criticise and hold authority to account. There is never a good time to shut down disagreement and deeper forms of scepticism. If anything, we need it more now than ever. So far, some of the overly optimistic rhetoric being generated by certain sections of the liberal press might suggest that we had better wake up quickly before it is too late.

Nick Stevenson is Reader in Sociology at the University of Nottingham.

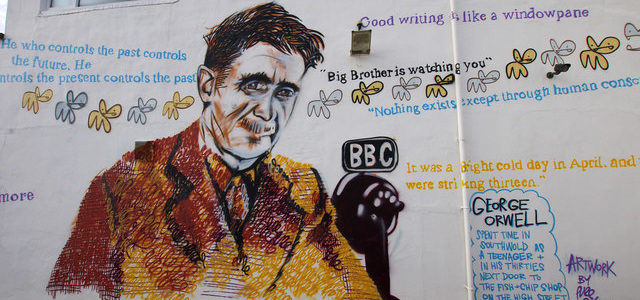

Image: George Orwell Mural, Southwold Pier. Ian Taylor