Anupama Ranawana

It is time, as Priyamvada Gopal says, to become “difficult dissidents” and “uncooperative naysayers”. It is time to take the fight to alternative spaces. Or, as Dorothy Day, doyenne of the Catholic Worker movement would note, “there is so much work to be done.”

Although Gopal was writing shortly after the result of the 2019 British elections were announced, and Day was speaking and writing whilst joining in civil disobedience that protested the Vietnam War, both point us towards this idea of radical solidarity, of organizing for change that is at the heart of progressive movements, and, importantly, at the heart of religious thinking also. As a new decade begins, it has become imperative for the religious left to reclaim political narratives and political agency, and to bring to the forefront the radical justice and social reformist agendas that are at the heart of much religious thinking.

The year 2019 was one of strange upheavals, stagnations and frustrations. It was also been a year of elections. In Canada, a Liberal premier with troubling neo-liberal policies managed to cling on to a small minority. In Bolivia, the re-election of Evo Morales caused weeks of widespread protests, and in South Asia, authoritarian governments in India and Sri Lanka were voted in with overwhelming majorities. In Brazil, a far-right dictatorship came to power under Jair Bolsanaro. Against this global background of increasing populism and fragmentation, the British public voted in a right-wing Conservative government with an astounding majority. Since the few weeks since the election, we have seen the legislative targeting of Roma communities, horrific anti-Semitic attacks in North London, increased instances of Islamophobia, members of Britain First signing up for Tory membership and a Brexit deal that de-regularizes worker’s and environmental rights.

To describe the pre-election atmosphere as febrile and festering would be something of an understatement. Prior to the calling of the election itself, the polarizing sword of Brexit had already cut deep divisions between communities, families, and workplaces. During the election campaign, other, more pressing issues, also received much needed discussion. Amongst these are the need for justice for the victims of the Grenfell fire, rife homelessness, a struggling NHS, the hostile immigration environment, worker’s rights, security, as well as institutionalized racism and prejudice that appears to be prevalent on all sides of the political divide.

It is this last that has brought religion, and religious voices quite prominently to the fore in this election. It was catalyzed by the Chief Rabbi, of the UK’s 62 orthodox synagogues, who wrote to the Times regarding his concern over antisemitism in the Labour party. Shortly thereafter, the Archbishop of Canterbury added his support to this intervention, closely followed by a statement from the Council of Muslims in Britain who, while supporting the Rabbi, also noted the concerns regarding Islamophobia in the Conservative Party. Although not through an official platform, there was also evidence of British Hindus being asked via WhatsApp and social media not to vote for the Labour party due to perceived anti-Hindu sentiment.

The worrying and dangerous trend here, is that in arguing for the protection of one’s own community only, religious communities become more insular and exclusionary. Such cleavages would add to the already deep and seemingly insurmountable divisions that the past few post-referenda years have brought. There is hope when solidarity is extended to the Jewish community from the Anglican Church and the Council of Muslims, but, it also highlighted, as the academic Gus John noted, the ongoing needs of black and minority ethnic populations rendered vulnerable by the prevailing political environment, and that Islamophobia is also a prevalent problem.

Indeed, as each community fought for their own needs, there seemed to be a ‘hierarchy of worth’ at play. Which minority, which community, which vulnerability must be most protected? This ‘hierarchy of worth’ stifles debate and negates participation, allowing for the fragmenting of the fight for radical justice into cloisters. To choose one community or vulnerability over the other is to immediately negate any anti-capital, anti-imperial, anti-black and, arguably, pro-plurality resistance. Further to this, the ‘silo-ising’ of faith communities from each other and from vulnerable communities, is itself a tactic of the far right, one which successfully delivered the presidency of Donald Trump. As the theologian J. Kameron Carter has noted, this separation of struggle allowed for the Christian religious narrative in the United States to concretize the legitimacy of the “melancholy of whiteness, of whiteness losing itself and violently trying to save itself….of the crisis of the religion of whiteness.” As column inches in the United Kingdom devote themselves to the problems of the ‘white working class’ we see strains of this crisis, this melancholy. In South Asia too, it was this suggested loss of ‘national’ identity that delivered the majorities of Modi and Rajapaksa, a melancholia for the loss of ‘authentic belonging’.

There is a great need, in British, and global public life, for radical solidarity, and this is the key role that religion and religious communities can play. This requires, of course, for religion to become wholly involved in public life, and for there to be a resistance to the kind of ‘silo’-ing of religious communities. Insularity in religion makes it more open to abuse from both internal and external actors. Religious actors can work together to build and encourage ecumenical and interfaith (including secular, atheist and humanist voices), in order to foster outreach between communities and to fight systemic prejudice and injustice together. As many political theologians have pointed out, robust public policy is essential for many of the key desires of faiths to come to fruition, such as an economically viable home life, radical human dignity, the rooting out of horizontal inequalities, and the opposition of war and violence. A recent and excellent example already exists in how Muslim and Anglican communities in Kensington banded together to act as mediators between authorities and those affected by the Grenfell fire.

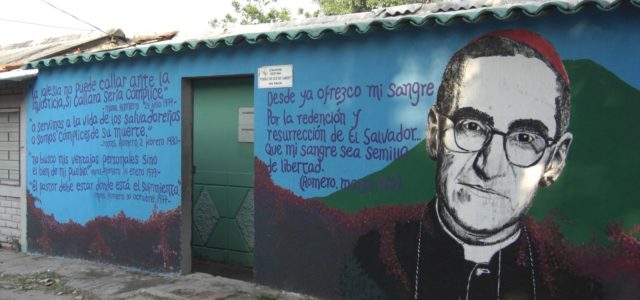

Extending radical solidarity and working across communities towards these collective goals of social justice is the liberative role that religion can play in public life. Interlocking, intersectional resistance can only occur through radical solidarity, something that is at the heart of much faith-lead thinking. For the sake of brevity, I will draw only from two specific examples – Catholicism and Buddhism. We have seen it in the liberation theology movements that stemmed from South America, where Gutierrez and others successfully, and theologically, rejected a static, bureaucratized religion and the separation between religion and politics, in order to grapple with dehumanizing socio-economic structures. Religious actors embraced their Marxist counterparts as members of a united struggle against injustice, within the understanding that neutrality and exclusivity were impossibilities. This, as the historian Hugh McDonnell has noted, is a tradition that needs revival as a necessary counterpart against the Christian evangelism that props up right wing governments.

This liberative stance is successful because, as Archbishop Oscar Romero urged, the focus was on being unafraid to “transform into flesh and blood, into living history”. Entering into history as lived and present is how radical solidarity begins. Another example can come from the South Asian theologians Aloy Peiris and George Soares-Prabhu when they note that the importance of the Christ figure is not his deity or his salvific role, but Christ the poor monk who teaches in the villages and organizes the struggle against Mammon, against the system that fosters injustice. Consider the nuns who broke into a nuclear facility as an act of protest, Christian activists who shut down oil pipelines, the nuns on the frontlines against misogynistic violence in India, and the religious actors on the front lines in America’s civil rights movements, who, in these instances are more in the person of Christ than a priest saying Mass.

In non-Abrahamic thinking, too, the fundamentals for this fight exist, as the anti-caste, anti-imperialist activist Dr B.R. Ambedkar realized in his harnessing of Buddhism as a ‘new vehicle’ through which the fight, at all levels of society, for human right can be channeled. As Ambedkar noted, the Buddha’s teaching was a religious revolution that became a social and political revolution exemplified by equal opportunity and the challenge to the infallibility of the Vedas. This understanding of Buddhism as a means for social reform comes from Gautama Buddha’s own thinking on anti-caste and anti-establishment matters, and influenced the Thict Nhat Hanh’s struggle against the Vietnam War, the struggle to free Tibet, and the establishment of the Sarvodaya movement in Sri Lanka.

It is no wonder that Ambedkar has become an icon for resistance against the CAA and the NRC in India this past December. Dr Ambedkar invited us to “Educate, Agitate and Organise”, a slogan that could be taken up again by the religious left in a broad, intersectional, interfaith movement.

Religions in the public sphere must take up this precise role, in the struggle against political division, and systems that perpetuate injustice. The religious left must reclaim their role in these struggles, and convince their communities to enter into living history, and work together to resist the right-wing establishment.

Anupama Ranawana is a theologian and writer who researches and teaches on South Asian Studies, faith and international development, liberation theology, feminist theology, race, ecological justice, feminist political thought and global political economics. Her doctoral work (Aberdeen) focuses on Buddhist feminist thought as an alternative site from which to understand the international. She is also a visiting researcher in the Department of Politics and International Relations at Oxford Brookes University.

Image Credit: Flikr- Alison McKellar