Marika Jalovaara and Anette Fasang

Nordic countries are well known for introducing a range of policies to support work – family balance and to increase social and gender equality. But to what extent do they achieve the aim of minimizing the family and gender gaps in earnings? We set out to answer the question in a new study based on data on almost 13,000 people in Finland and find a rather disappointing answer.

A range of studies have already shown us how partnerships, marriage and parenthood can be related to our earnings. In the US, for example, men who are married with children enjoy a substantial earnings advantage known as the fatherhood premium, while divorced fathers and stepfathers have no earnings advantage compared to childless men.

A forthcoming study of women born between 1943 and 1963 in 22 European countries finds that married women with children have the lowest earnings in later life.

So how do the more generous and egalitarian policies in Nordic countries affect what people earn? Do they help compensate for any loss of earnings associated with becoming a wife and a mother? And if there are economic consequences to becoming a parent – in terms of earnings – how long do they last?

We already know that women in Finland, compared with those from other countries, are more likely to work after they have children. However, they do tend to take longer family leave than men, supported by a generous system of home-care allowances and job-protected rights to parental leave.

While earlier studies have tended to focus on the earnings of either men or women, we wanted to compare the earnings of men and women with different types of family lives over time. Our thinking was that, although in a country like Finland having children may not negatively affect women’s earnings so much compared with women who don’t have children, there could still be big gender gaps within family situations. This in turn might then counter the egalitarian goals of the Nordic welfare model, if men with specific family lives have much higher earnings compared to women with the same family lives.

Rich data

We analysed rich data on 6,621 men and 6,330 women born in 1969 and 1970 compiled by Statistics Finland. This represented an 11 per cent random sample of the population and linked the population register with data on employment, educational qualifications, demographic events, and income from taxation registers. Family histories from ages 18 to 39 were created using a technique called sequence analysis originally designed to group strands of DNA.

We found seven different family life course types:

- Late marriage, 2+ children (16%)

- Marriage, <2 children (11%)

- Early marriage, 2+ children (19%)

- Childless serial cohabitors (10%)

- Cohabiting parents (12%)

- Unpartnered parents (9%)

- (Almost) never-partnered childless (23%)

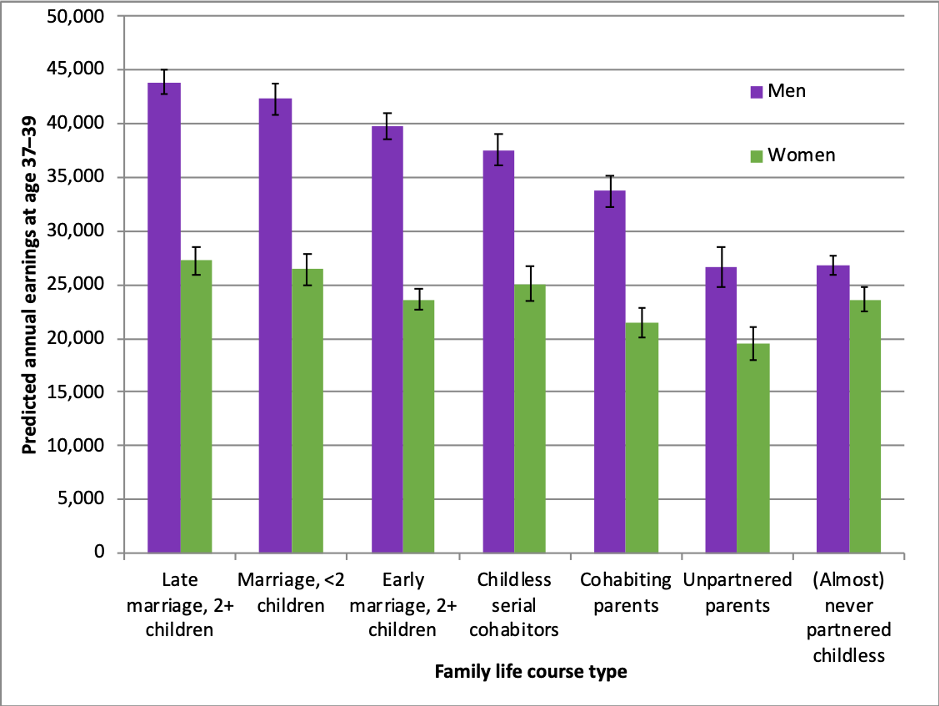

When it came to earnings, we looked at these for both men and women at around age 40 (Fig 1.) as well as their accumulated earnings from 18–39. Accumulated earnings sum up all earnings a person had between age 18 and 39. They are a better indicator of overall economic standing, because they show to what extent individuals could consume, save and invest during early adulthood.

Stable marriage and parenthood

As we expected, the first three family life course types involving stable marriage and parenthood were associated with higher mid-life earnings. Interestingly, the differences were much larger for men than for women, that is, men profit much from following being married and having children in terms of earnings.

Figure 1. Average earnings at ages 37–39 for men and women with different family life courses*

Women, too, benefited from marriage and parenthood, but not to the same extent as men. Their earnings were higher if they had children and a long marriage compared to unmarried mothers and childless women, but overall earnings differences between women were much smaller regardless of their family lives.

Why is this? Previous literature suggests that family instability is associated with lower earnings. But in our study the issue is not purely one of family stability – men who have never had a partner (or just very briefly cohabited) and remained childless, who might be thought to have had very stable lives in family terms – had lower mid-life earnings. This group (more than one in five of men in our study) is one we believe should be considered a social risk group by policy makers and researchers, because they have the lowest earnings among men and may not have a family network to fall back on.

The difference seems to be that the Finnish welfare state has facilitated and rewarded the combination of marriage, motherhood, and gainful employment more generously than most countries through its system of benefits and parental leave rights. However this appears to have done little to address the earnings disparity between married fathers and married mothers – another area we believe should become a focus for those interested in tackling inequality and creating fairer and more equal societies.

The Finnish system certainly supports family life and work, which might lead to mothers taking longer family leave, which in turn could lead to lower accumulated earnings. But it doesn’t really explain the large difference in earnings between men and women at near age 40, when employment rates are the same and when both women and men tend to work full-time. Neither does education play a major role here, because, on average, women in Finland are in fact higher educated than men.

What this tells us is that when we look at these issues we have to compare women’s situations with men’s, rather than simply comparing mothers with childless women, which has tended to be the focus to date.

We also need to better understand what is going on when it comes to the accumulated disadvantage faced by the lowest-earning group of men – those (almost) never-partnered and childless, especially because fertility has been falling with a remarkable level of lifetime childlessness in Finland. However, we should note that childless never partnered men earn on average as much as the women in the highest-earning family group, which underlines the remarkable gender earnings gap irrespective of family lives even in this Nordic egalitarian welfare state.

The main story

In the Nordic welfare states, the main story is not inequality between mothers and childless women but between married mothers and married fathers. In addition there are new social risk groups which have previously escaped notice and which need to come to the forefront of all those interested in tackling inequality.

Looking at how inequality develops within and across different family lives is key in terms of how we need to approach these problems going forward.

We set out to see if the Nordic egalitarian model really lives up to its promises. The answer is ‘not really’! There are some clues here about how policymakers with egalitarian goals might make the answer ’yes’.

* Note: The figure shows estimates from a regression model without additional covariates. The mean earnings differences remain similar when factoring out a number of covariates including education, childhood place of residence, and parental characteristics. The black lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Marika Jalovaara is a Senior Research Fellow at the Department of Social Research, University of Turku. She is the PI of the project ‘Falling Fertility and the Inequalities Involved’ (NEFER) and a CoPI in the ‘The Inequalities, Interventions, and New Welfare State’ (INVEST) Flagship, both funded by the Academy of Finland. Her research interests include linkages among family dynamics, social inequalities, gender, and the welfare state. Anette Eva Fasang is a Professor of Microsociology at Humboldt-University of Berlin and Head of the research group Demography and Inequality at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center. Her research interests include social demography, stratification, life course sociology, family demography, and methods for longitudinal data analysis.

Family Life Courses, Gender and Mid-Life Earnings is published in European Sociological Review and was produced as part of the NORFACE-funded Equal Lives Project which is taking a lifecourse approach to investigating the impact of inequality on young adults in 5 countries.

You can listen to Marika and Anette discussing the research on the Equal Lives Series of the DIAL Podcast.

Image: Kevin Lamarque