Dimos Sarantidis

The silencing of refugees’ voices has been discussed in various ways. For example, the refugee, Malkki argues, is commonly represented by virtue of being a refugee—a powerless subject suffering with no political voice. In Fassin’s words, refugees are not allowed to voice political rights, but to only appeal to a common humanity by showing their wounds. This appeal to compassion reproduces biopolitical power and reduces the refugee to a wounded body—to biological, bare life, that denies recognition of political agency. In this article, I will focus on the overlooked voices of refugees and the importance of these voices being heard, not only through intermediaries and activists showing solidarity towards refugees, but also directly by refugees themselves. By referring to some of my own experiences as a lawyer supporting border crossers in Greece until 2015 and as a researcher conducting fieldwork on Lesvos afterwards, I will refer to some characteristic examples showing how refugees’ voices have been silenced but also demonstrate the multiple ways in which their voices can be heard through some good practices. As I will argue, giving voice directly to refugees is an important prerequisite for a substantial change regarding refugees’ dignity, human rights and socio-political existence.

Some History

Before 2015 and the beginning of the so-called “refugee crisis” I worked as a lawyer and NGO worker at various refugee detention facilities in Greece by providing legal aid for refugees. During the period 2009-2010, I was working at the Pagani detention centre, perhaps the most infamous refugee camp in Europe during this period. Pagani, which had been operating since 2005, was a closed detention centre and a place in nowhere. Its existence and most importantly the human rights violations taking place within the camp had received minimal attention by the EU, the Greek state, the media and humanitarian actors. When I gained access at Pagani, I noticed that the appalling living conditions, the inadequate access to asylum, the social harm and violence refugees were experiencing were filtered and silenced to the outside world to a large extent by the authorities—the Greek police and Lesvos prefecture—administering the camp.

By witnessing this situation, a main aim on behalf of my colleagues and myself became the issue of raising awareness. After finishing our work at Pagani, we were arranging meetings with local grassroots movements and journalists in order to explain to them the situation and most importantly, to explore how we could give voice to refugees detained there. Simultaneously, we started sharing information with the NoBorder Network, consisting of associations of autonomous organisations, groups, and individuals in Europe and beyond. In summer 2009 hundreds of activists arrived on Lesvos and a NoBorder Camp started operating. Apart from the participation of international and local activists, former detainees from Pagani undertook a vital role by providing first-hand information on their experiences. Activists, working together with refugees through direct actions, demonstrations, anti-deportation campaigns and short videos taken by refugees detained inside Pagani, gave rise to refugees’ voices and unveiled the human rights violations, which were silenced for many years.

As NGO workers we were intimidated by the authorities for speaking publicly about the situation at Pagani, while the refugees undertaking hunger strikes, protesting inside the detention centre and speaking publicly about ill-treatment by the authorities were aware that this could affect their future treatment by the Greek authorities. Despite these difficulties, all of those protesting and campaigning were determined that this enduring injustice at Pagani should come to an end. Under this pressure, the Greek Minister for the Protection of Citizens visited Pagani in October 2019, and described it as “worse than Dante’s inferno”. Afterwards, the government announced the release of the almost 1,000 refugees detained and the closure of Pagani. The closure of Pagani would have been impossible if refugees, locals and international activists had not put their voices together to criticise the politics of refugees’ detention and raise awareness of issues such as the freedom of movement and human dignity. Pagani became for me an illustrative example showing that unjust border policies can come to an end and even a detention centre can close if the voices of the people affected by these policies are heard.

Present and Future

Present and Future

In September 2018 I visited Lesvos again, this time not as a lawyer but as a researcher conducting fieldwork for my PhD. In the aftermath of the 2015 “refugee crisis” Lesvos was transformed into an open prison, a “prison island” as refugees call it, where up to 12,000 refugees were stranded for months or even for years. The enforcement of the EU-Turkey Statement, followed by a “geographical restriction” of refugees’ movement on Lesvos had created a suffocating environment for refugees, but the main difference in comparison to the case of Pagani was that Lesvos had become a spectacle. The border became the spectacle of death and suffering to such an extent that Lesvos became suddenly a famous destination, attracting celebrities, volunteers, journalists, academics, and NGOs to observe the phenomenon themselves, provide solidarity to refugees and humanitarian aid. Before visiting Lesvos, I was systematically having conversations via Skype and email with members of my pre-established network consisting of activists and former colleagues. I was thus aware of the violence and injustices taking place inside the camps and wondering why all the above-mentioned actors, especially those working inside the camps, were not publicly speaking about these issues. In September 2018, three years after the beginning of the refugee crisis, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) finally broke the silence and spoke publicly about child refugees attempting suicide and self-harming, and the horrible conditions in Moria, the biggest refugee camp on Lesvos. The rest of the actors in Moria did not make any comments. As one of my interviewees told me “they just indirectly supported MSF, by not refuting their sayings”. A local activist and NGO worker commented, “some of the big international actors are trying to control activists and NGO workers. They told us ‘you are not allowed to put out information’. They are funded by the EU and they do not want to criticise the outcomes of the EU border policies”. Similarly, another interviewee referred to the restrictions he faces, as a representative of a well-known INGO; “currently my NGO participates in an advocacy group, where activists and NGOs participate. Activists condemn the EU-Turkey deal, but for us, as representatives of bigger NGOs this is not the case; we are telling them that, ‘we agree with you’, but we are not allowed to officially condemn these policies”.

The above are only a few examples of how some humanitarian actors can silence refugees’ voices, in the context of the refugee crisis in Greece. However, as in the past, Lesvos still serves as a case study suggesting that refugees voices can be heard in various ways. For example, in autumn 2017 several protests and demonstrations took place. Refugees had occupied the central square in Mytilene, the capital of Lesvos, for many weeks, in order to oppose the EU border policies and fight for freedom of movement and human dignity. The police finally evicted the square, but refugees and activists responded by occupying the local office of the ruling party SYRIZA. This initiative attracted much publicity and as a local lawyer assisting refugees told me, “this was a good practice, showing how refugees’ voices can be heard, because within a week the Greek state revoked the geographical restriction for many of them”.

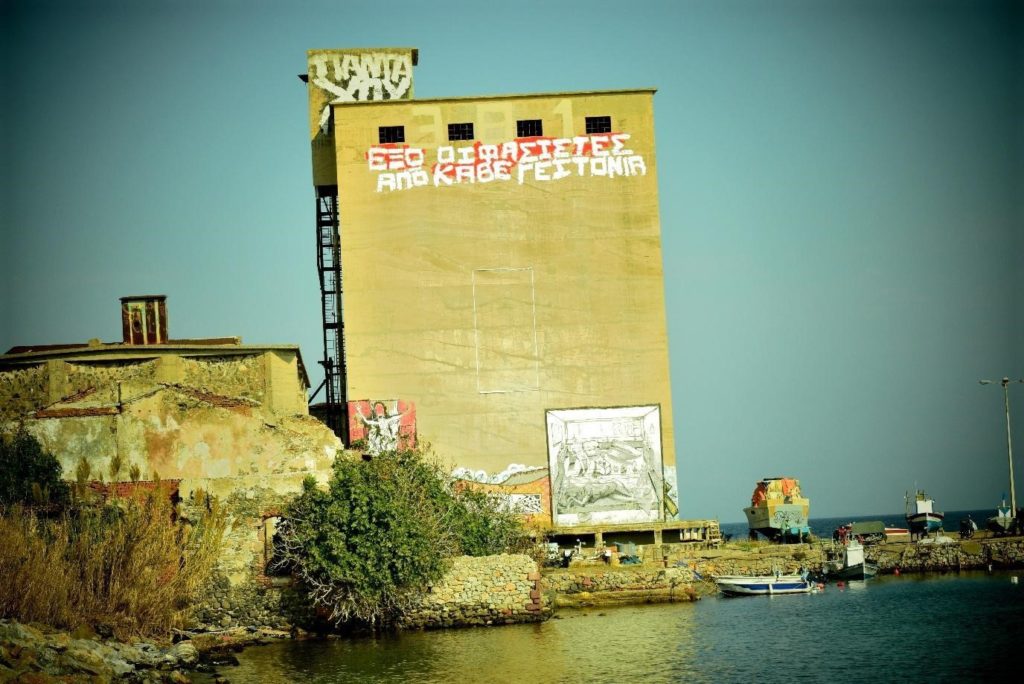

“Kick out fascists from every neighbourhood”, written on a Mytilene abandoned building. Picture taken by Dimos Sarantidis

According to the above-mentioned examples, there are multiple ways for refugees’ voices to be heard. Nevertheless, there is a need for collective actions, performed not only by activists, but most importantly through the participation of refugees themselves. In this way, refugees are not objectified and can become equal participants in debates concerning their own lives. Before 2015, when I was a member of grassroots movements in Lesvos, during assemblies we frequently discussed how we could resist unjust border policies. There were frequent disagreements and different opinions expressed. However, the answer was often very simple: “why don’t we ask refugees themselves to tell us? We cannot decide for them without them”. This collective process of engaging activists, local people and refugees led to structural changes, like the cancellation of deportations or even the establishment of open camps, administered by locals and refugees themselves. Until then the operation of closed detention facilities was the rule.

Regarding the humanitarian actors operating in border spaces like Lesvos, I strongly believe that they all need to be honest about what they really witness, instead of silencing injustices taking place within camps. Safeguarding human dignity and resisting obscene border policies should be prioritized over gaining access or securing EU funding to ensure genuine and effective humanitarian support. Regarding scholars and researchers, it would be ideal if refugees’ voices could directly be heard. Giving them the opportunity to participate and speak in conferences, workshops and debates, or encouraging them to individually or collectively contribute to academic journals and blogs will not just amplify their voices but will practically show that they are treated as equal participants in a debate, which mainly involves their own lives.

Dimos Sarantidis holds a BA in Law and an LLM in International Criminal Law. His research background is on human rights, refugee law, and critical criminology. In the past he has worked as a lawyer by providing legal aid to border crossers. His current research is on the “refugee crisis” and the overlooked voices of local populations on Lesvos/ Greece.

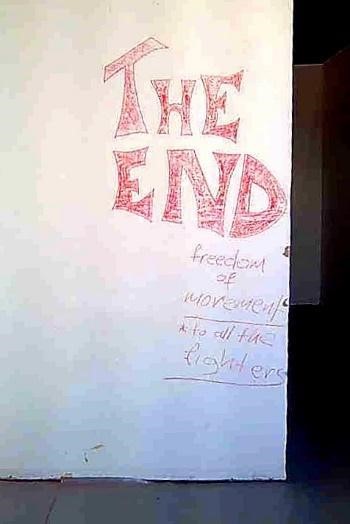

IMAGE CREDIT: “Destroy all prisons”: A part of Moria’s camp wall. Dimos Sarantidis