Jil Matheson

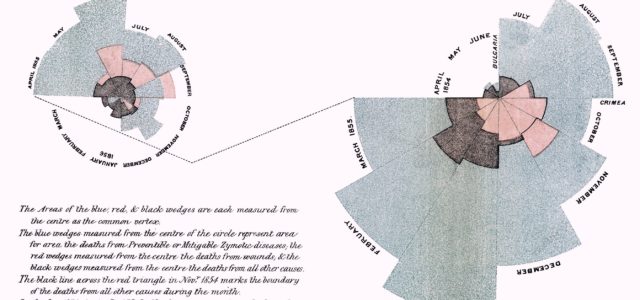

In celebrating women’s contribution to social science (and I include statistics) over the last 50 years we should acknowledge that our contribution did not begin in 1969. Florence Nightingale became the first female member of the the Royal Statistical Society (RSS) in 1858. She recognised the power of data, collected systematically and presented visually, to change, among other things, health policy and nursing practice. She lobbied the powerful relentlessly until the evidence could not be ignored.

Nevertheless it took until 1975 for the RSS to have its first female President, since when there have been four (with a fifth as President Elect). The changing role of women in the last 50 years can be traced in the working lives of female social scientists and statisticians, in methodological practice, and in the topics of research. NatCen Social Research is also celebrating its 50th birthday (founded as Social and Community Planning Research (SCPR) in 1969) and the list of surveys it and others, in particular the Social Survey Division (founded in 1941 and now part of the Office for National Statistics), have carried out over the last five decades is a fascinating resource for understanding the issues on the minds of government and policy makers. The growing debate in the late 1960s and 1970s about the role of women contributed to the development of statisticians who saw their role, in part at least, as being to shed light on the experiences of women, and of other groups, in the statistics they produced.

Recognition should be given too to a group who are often overlooked, but who have contributed hugely to the UK’s rich tradition of social surveys – interviewers. The Sex Discrimination Act in 1975 brought to an end, albeit slowly, the widespread practice of employing all-female interviewer field forces, widely believed to be working for ‘pin money’ – a phrase I heard often as I began my own career.

Data on the composition of the social sciences workforce are hard to come by. Even in my own part of that workforce, the Civil Service, figures on the numbers and characteristics of social researchers, statisticians and economists are not easy to track down for the whole of the period. But we do know that by 2015, 66% of social researchers, 45% of statisticians, and 35% of economists were women, increasing from 29%, 17% and 7% respectively in 1970. But only 29% per cent of economists at the most senior levels, the Senior Civil Service (SCS), are women. This isn’t just a cohort effect. It reflects the wider picture of a ‘leaky pipeline’ just below the SCS although there has been significant progress in recent years: in 2018, 43% of the SCS as a whole were female, compared with 32% 10 years earlier and just 21% in 2001.

Beyond the Civil Service the continuing challenges facing women in statistical careers are highlighted by the creation in 2019 of a new RSS ‘Women in statistics and data science’ group. Its remit is to:

- increase the visibility of women in statistics and data science careers

- advocate for opportunities for women in statistics and data science

- support women in the field of statistics and data science;

- share experiences to advocate for women

This is timely. Part of the response to the growth of data science has been to introduce a new ‘A’ level in computing. It is startling that this is now the most gendered A level of all. Twelve per cent of entrants were female in 2018, significantly lower even than the 22% for physics and 39% for maths. A 2019 report from the Royal Society, Dynamics of Data Science Skills, expresses the concerns well :

‘Women make up a disproportionately small fraction of the educational pipeline associated with data science positions…This is particularly relevant as the development of data science talent needs a wider set of skills, including those involved in identifying, understanding and interpreting real-world problems. A diverse pipeline of data scientists is more likely to pick up or be concerned by inadvertent biases in algorithms that can impact on many different types of people’.

An example of how feminist thinking impacted on statistical practice was the change to the definition of ‘Head of Household’ (HoH) which was used in official statistics until the 1990s although the ‘normative basis of the definition’ (Bruckweh) was beginning to be challenged from the 1960s onwards. The 1991 official Handbook for Interviewers continued to define the Head of Household as: ‘In a household containing only husband, wife and children under 16 (and boarders) the husband is always the HoH. Similarly when a couple have been recorded as living together/cohabiting the male partner should be treated as HoH’, even though a previous edition of the Handbook in 1984 had begun to sound apologetic . It observed that ‘these rules were necessary because the use of joint heads of household is not practical for analysis purposes. Because of this it is necessary to have consistency in the way in which definitions are made’.

Gerald Hoinville and Roger Jowell, founders of SCPR, wrote in 1982: ‘Some of these rules are increasingly under attack on the grounds of their male chauvinistic bias and the fact that they are anachronistic…Nevertheless current practice is still to define the head of household as the husband’. It wasn’t until the 1990s that options for change were seriously discussed in official statistics (Martin and Barton, SSD Survey Methodology Bulletin, 1996 ) and the Household Reference Person(HRP), the Householder, and Chief Wage Earner were suggested as additional or alternative classifications.

The HRP was introduced from 2001. ‘The household reference person is the household member who owns the accommodation, or is legally responsible for the rent; or occupies the accommodation as reward for their employment, or through some relationship to its owner who is not a member of the household. If there are joint householders, the one with the highest income is the household reference person. If their income is the same then the eldest one is the household reference person’. Whilst no longer explicitly gender-based, it is likely that the indirect effect is to favour men over women. The choice of classification matters when statistical series classify households and their members according to the characteristics of one person – whether its the HoH, HRP or Chief Wage Earner. One of the most important statistical series – life expectancy at birth by social class – was based on father’s occupation (where it is recorded on the birth certificate) because it was not until 1984 that the law was changed to enable mother’s occupation also to be recorded. Consistency over time is always an important consideration for statisticians, but the choice of classifications, and their underpinning assumptions, must be subject to regular scrutiny.

The history of Social Survey Division, published to mark its 60th anniversary, provides an insight into the policy concerns of the day. Many surveys covered both men and women, but some topics were clearly seen as relevant to one gender only. In the 1950s the survey programme included studies of ‘Food retailing and the Housewife’ (Moss 1957) and ‘The Housewife and the Garchey system of refuse disposal’ (1958), whilst in the early 1960s a survey was carried out on ‘Deterrents and Incentives to Crime Among Boys and Young Men aged 15 to 21’ (Willcock and Stokes, 1963). Surveys on smoking have been carried out regularly since the 1960s. Bynner’s ‘The Young Smoker’ would have been better called the Young Male Smoker. It wasn’t until the 1982 survey of Smoking among Secondary School Children (Dobbs and Marsh) that girls and boys were both included.

Surveys have for a long time tracked changing employment patterns and attention began to focus specifically on women at work towards the end of the 1950s, with a survey of the ‘Employment of women scientists in industry’ (Thomas and Morton Williams, 1959). This interest in women continued in to the 1960s and 1970s (Survey of Women’s Employment, Hunt, 1965; Management Attitudes and Practices Towards Women at Work, 1973; Fifth Form Girls: Their hopes for the Future, Rauta and Hunt; Women and Shiftwork, Marsh, 1979; Women in Employment: a lifetime perspective, Martin and Roberts). Men’s employment did not escape attention. In the 1960s surveys were carried out of ‘Attitudes towards a career in the regular army amongst young men aged 15-21’(Sillitoe, 1963), and ‘Factors associated with the movement of qualified men teachers from maintained schools’ (1969).

More recently attention has turned to measurement and reporting of the gender pay gap, and the continuing under representation of women in particular occupations and in senior positions. The most recent report, from the Equalities and Human Rights Commission, Is Britain Fairer? (2018) noted the lack of any regular statistical source on sexual harassment.

Florence Nightingale – with her systematic collection and graphical presentation of relevant data – is a founding mother worth celebrating.

References

Florence Nightingale, the Woman and her Legend. Bostridge, 2008

The Head of Household. A Long Normative History of a Statistical Category in the UK. Kerstin Bruckweh. Administry. Vol 1 Issue 1 2018

Acknowledgments

With thanks to Ross Young, Office for National Statistics, and Joy Dobbs, former Head of Social Survey Division, ONS for their help .

Jil Matheson served as National Statistician, Head of the Government Statistical Service and Chief Executive of the UK Statistics Authority from 2009 until her retirement in 2014, following a career in social research and statistics. During that time she also Chaired the OECD’s Committee on Statistics and Statistical Policy and the UN Statistical Commission. More recently, she led a group for the British Academy on the need for improved quantitative skills in the UK, and carried out a review of the BBC’s use and reporting of statistics, ‘Making Sense of Statistics’ published in August 2016. She is a Trustee of NatCen Social Research