Jagdish Patel

When I was asked to write about the events in Southall, 79, history and art, I was drawn to the words uttered by bandleader of Misty in Roots, Smokes, on their live album recorded in 1979.

“When we trod this land, we walk for one reason. The reason is to try to help another man to think for himself. The music of our hearts is roots music: music which recalls history, because without the knowledge of your history, you cannot determine your destiny; the music about the present, because if you are not conscious of the present, you are like a cabbage in this society; music which tells about the future and the judgment which is to come.”

After these words the keyboard, played by Vernon Hunt, starts loudly, and we enter the black aesthetic that is reggae, with its revolutionary ferment on history, politics, culture, and society.

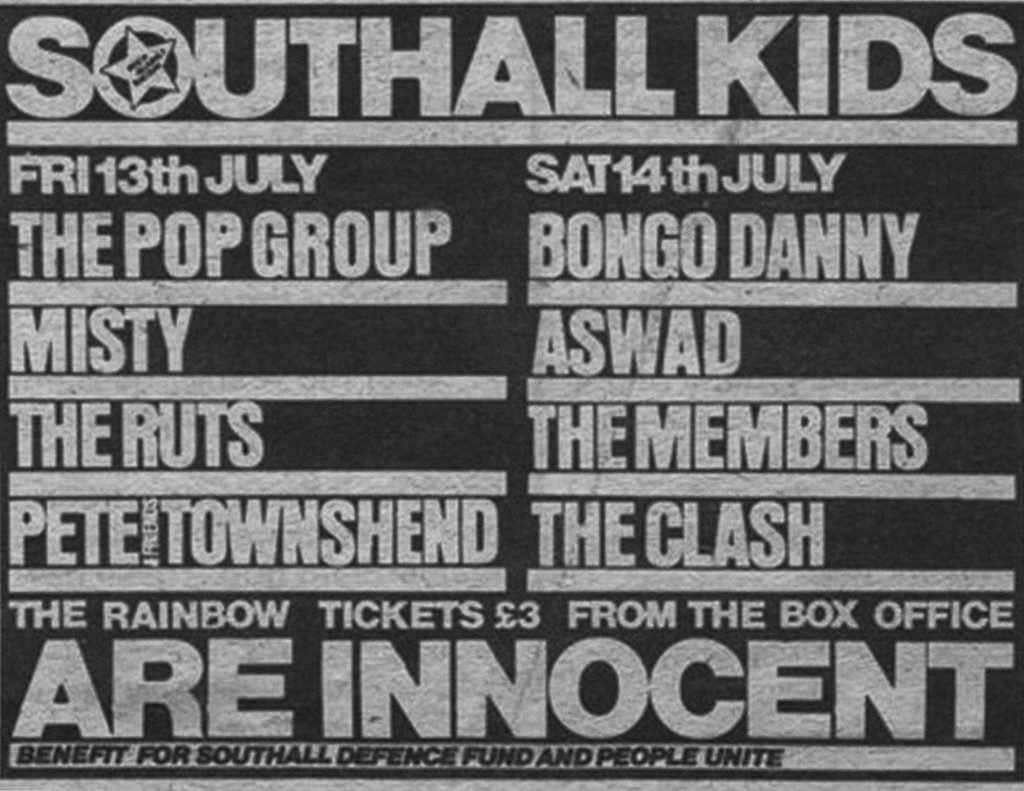

Misty in Roots come from Southall. Many of the members arrived in Southall from the Caribbean as children in the early 1960s and continue to live in the town. As most Southall residents, they were present on the 23rd April 1979. Many members were beaten by police in the Peoples Unite Creative and Art centre and falsely charged. Some like Vernon were also jailed, left prison broken and never played music again. Eve Turner was in the building and would later testify in defense for many of those arrested. This is just two of the hundreds of stories from Southall from that day.

We chart our lives with memories, and these determine how we see ourselves. The act of remembrance is also a social event, connecting us to other people and to places. However, a historical narrative not only frames the past, but its temporal relationship to us also tends to make it future-oriented. Politicians know this, and it was no accident that the Brexit slogan ‘Taking Back Control’, talks to a certain constituency both about the past and future.

If we accept that how we talk about Southall’s past is important, what issues should we consider?

Firstly, Southall, like Handsworth, Tottenham, Brixton and Toxteth are important cultural and political places, even for people who don’t actually live there. Mainstream media would let you believe that these are town are crime-ridden, poor and dangerous. This is so far from the actual reality. Southall contrasts to the drab west London towns of Ealing, Hayes or Hillingdon. It is a bustling place, with plazas, a shared Southall culture, often present on the streets, and a vibrant shopping centre which is as busy as Oxford street. People come here from all over the country just to experience this. Can you imagine how successful a cultural arts centre would be here?

Secondly, there is an absence of interesting art projects documenting Britain’s Black and Asian histories. One of the few is ‘Handsworth Songs’. It is about riots in Handsworth and London and was made by intermixing newsreel, still, photos and a sound mosaic, creating an experimental multi-layered narrative. The film led to a public argument between Stuart Hall, Darcus Howe and Salman Rushdie, with Rushdie remarking, “If we know why the caged bird sings, let’s listen to her song.” How local voices are documented and used publicly is important.

This is also important in research. In 1999 the sociologist Ben Bowling wrote ‘Violent Racism’ in which he studied everyday racism experienced by victims and the response from state agencies. He noted that there was a wide discrepancy between victims and state agencies in how a single racist incident may be interpreted, rooted in wider historical and ideological differences. Over recent years, this has worsened, especially in criminology.

Nowadays, the discourse around hate crime laws and policies disconnects the agencies from the actual racism present in people’s everyday lives. Bowling’s methodological approach was to listen to people. It is ironic that as more and more academic departments produce reports on ‘hate crime’, the use of critical ethnography to allow participants voices to be heard has slowly disappeared, as researchers tend to rely more and more on quantitative data. Moreover, as race equality councils and monitoring groups have disappeared, the discussion around tackling racism has become wholly sidelined.

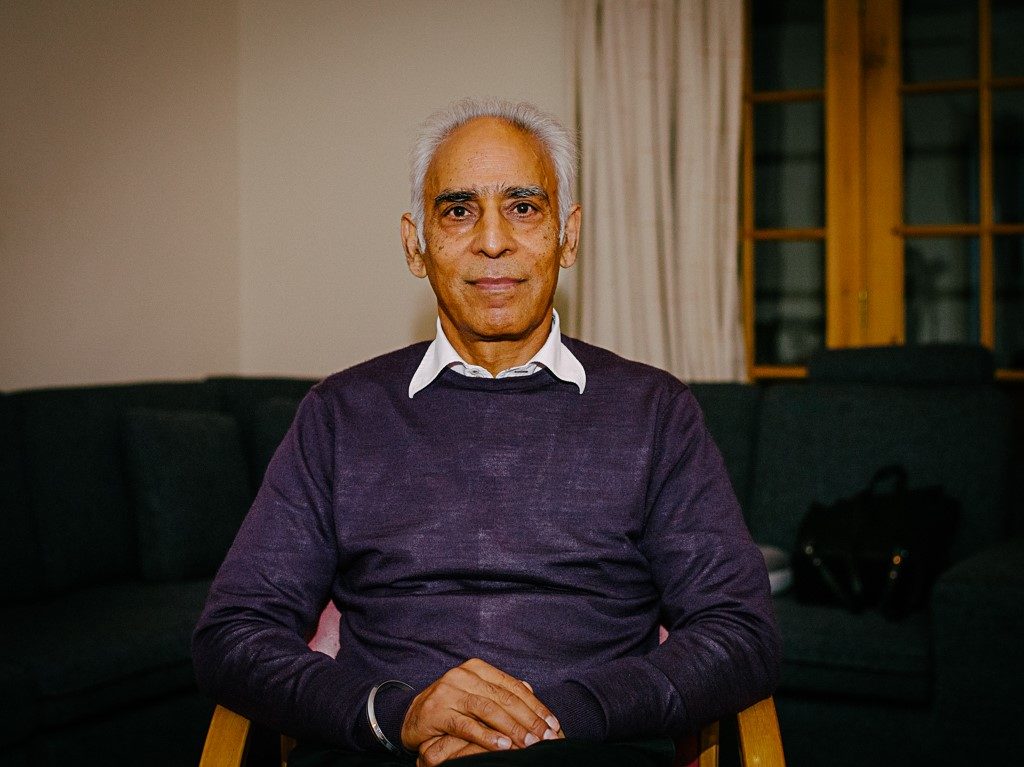

Listening to people is important in how you interpret the past. People came to Southall from India, Pakistan and the Caribbean onwards from the 1950s. Most of the incoming migrants came from rural areas, with a post-Independence optimism, and a sense of independence and self-reliance common amongst rural communities, even farmers in Britain today. They also bought with them the left progressive politics of the colonial movements, and the Indian Communist Party and this was reflected in how they saw themselves in Britain. One of the few people documenting this past is Balraj Purewal, former leader of Southall youth Movement.

These early settlers, like Vishnu Sharma campaigned within a variety of places including the Transport Workers Union, the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD), the West Indian Standing Conference and the Indian Workers Association. At the same time, they took participated with their faith community, temples, mosques and gurdwaras. In their eye, these competing identities worked together. If we look at the people invited to speak in Southall, we see people such as Fenner Brockway, Claudia Jones and George Pargiter. Not only are these early radical stories largely forgotten, but there is a tendency to argue that radical politics only started in 1976 with the second generation, the Southall Youth Movement and other groups. Forgetting, for example, the work of Mrs Lakhbir Bains who arrived in Southall in 1954 and set up the Southall Women’s & Girls Group in the early 1960s, or Avtar Brah, one of the founders of Southall Black Sisters, two stories of the many stories which are interlinked.

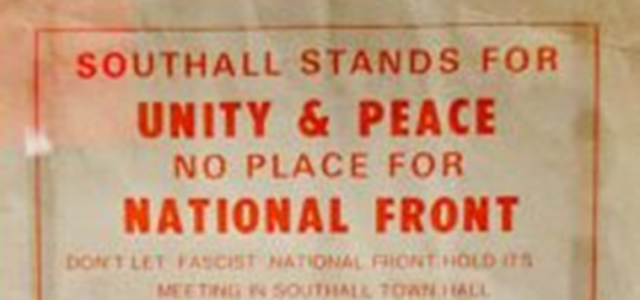

The story of Southall in 1979, is also part of Britain’s far-right legacy. The Southall Residents Association was set up in the early 1960s, and by 1963 the BNP was so popular in Southall that it gained 27% of the votes in the council sending the Tories to third place. During this period, conflict with either far-right members or far right rhetoric was a daily reality for Black and Asian families.

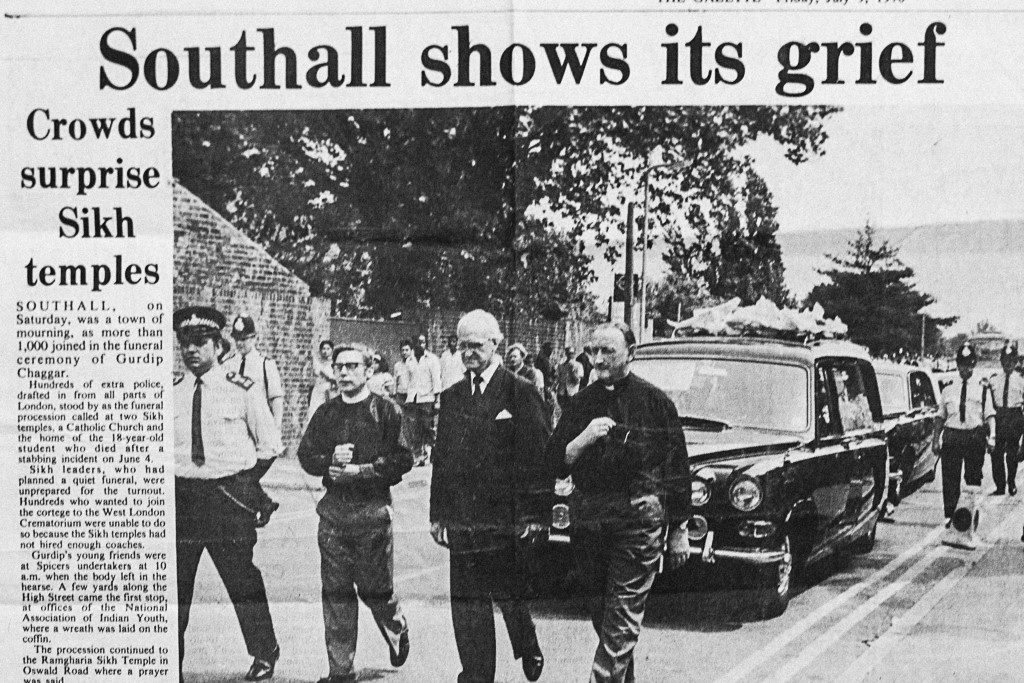

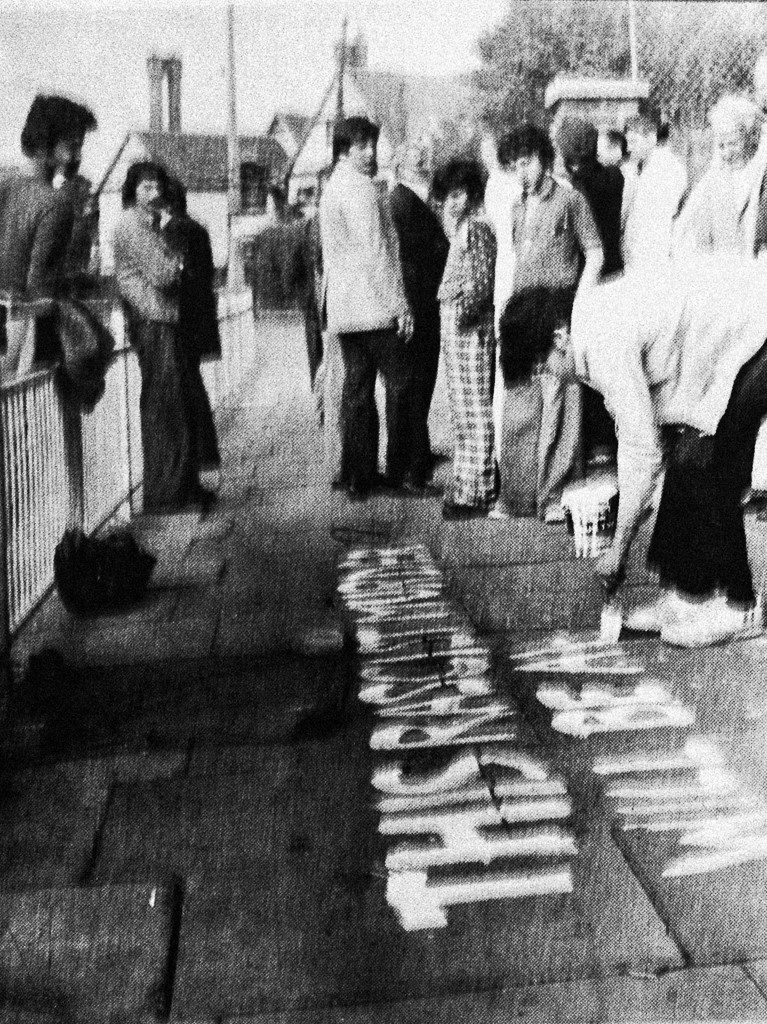

In 1976, a young Southallian named Gurdip Singh Chagger was stabbed to death by a group of white youths outside the Dominion Cinema and the headquarters of the IWA. There is a photograph showing a young Suresh Grover and his friend writing ‘this racist murder will be avenged’ on the pavement. Years later Suresh would be helping another family whose son was murdered in racist attacks, Stephen Lawrence killed on 22nd April 1993.

Image 9: Suresh Grover with friend at Chagger’s murder scene, June 1976 @ Archives of Chagger family

In April 1979, alongside Southall other communities also faced heavily policed National Front meetings. On April 20th, 2,000 police officers were deployed in Islington, on 21st April, 5,000 police officers were deployed in Leicester, in Southall, nearly 3,000 police officers were deployed, and on 28th April 5,000 police were deployed in West Bromwich.

Balwinder Rana, the main Steward in Southall had been in Leicester two days previously on the 21st, and even got arrested. Having seen the violence erupt in Leicester he was part of a delegation which tried to ban the march in Southall. Not only was this not successful, on the day he was totally ignored as the chief steward, having been hit and then chased by the police.

The Labour leader at the time was Jim Callaghan, nicknamed ‘Blue Jim’ because of his close relationship with the Police Federation. As Home Secretary he sent the troops to Northern Ireland, enacted the 1968 Commonwealth Act, effectively separating black and white commonwealth citizens, and established the Special Demonstration Squad, an undercover policing unit. In 2012 we learnt that the Unit was active in Southall, targeting Celia Stubbs, partner of Blair Peach, the Monitoring Group, and the Stephen Lawrence campaign. Ironically, the mock stamp produced by artist Peter Kennard in commemoration of Blair Peach was later remade to show the surveillance of activists by the police.

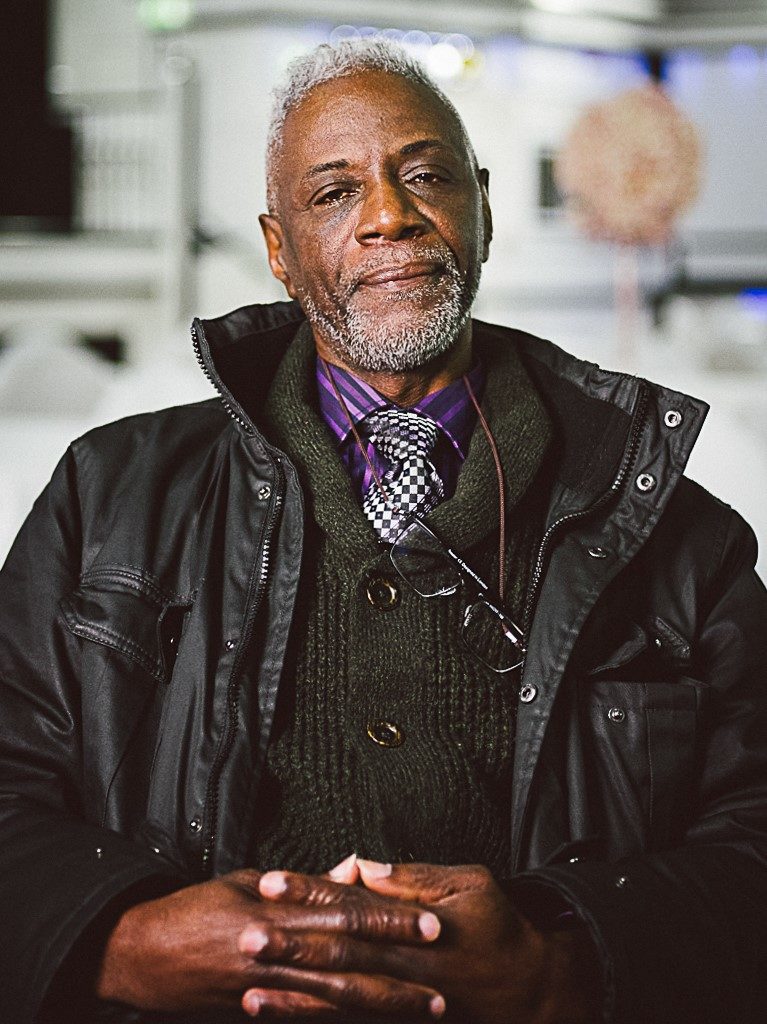

Clarence Baker, former manager of Misty in Roots, was beaten unconscious during the police raid on the People Unite Creative and Art centre. When he awoke Thatcher was the new Prime Minister of Britain. The story of heavy policing continued, and the events of 1981, the Miners Strike, the events of Tottenham in 1984 were a continuation of the Southall story.

The events in Southall resulted in a community becoming politicized and led to a whole generation campaign for justice for Blair Peach, and the people arrested. It represented a watershed in the creation of new youth politics, not just in Southall, but across the country, and this story is still largely unknown.

When a local primary school was named the Blair Peach school, it was quickly renamed by an incoming Conservative council, only to be renamed again when the Conservatives lost power. Now it is still called the Blair Peach, though without any reference to the events of 1979 present in the school. In 1985, artists Chila Kumari Burman and Keith Piper were commissioned to create the ’Southall Black Resistance Mural’. This became steeped in controversy after complaints. The council refused it planning permission for a permanent location, and after some time it was rumored to have been destroyed. A new generation of artists, like Philly K Bhambi, are still trying to revive this tradition.

The state has consistently refused to let the community tell their story for many years. The result is a younger generation talk about these events with the same language used in mainstream media, and a recent school art project still represents these events as a ‘race riot’, yet no one rioted on the day.

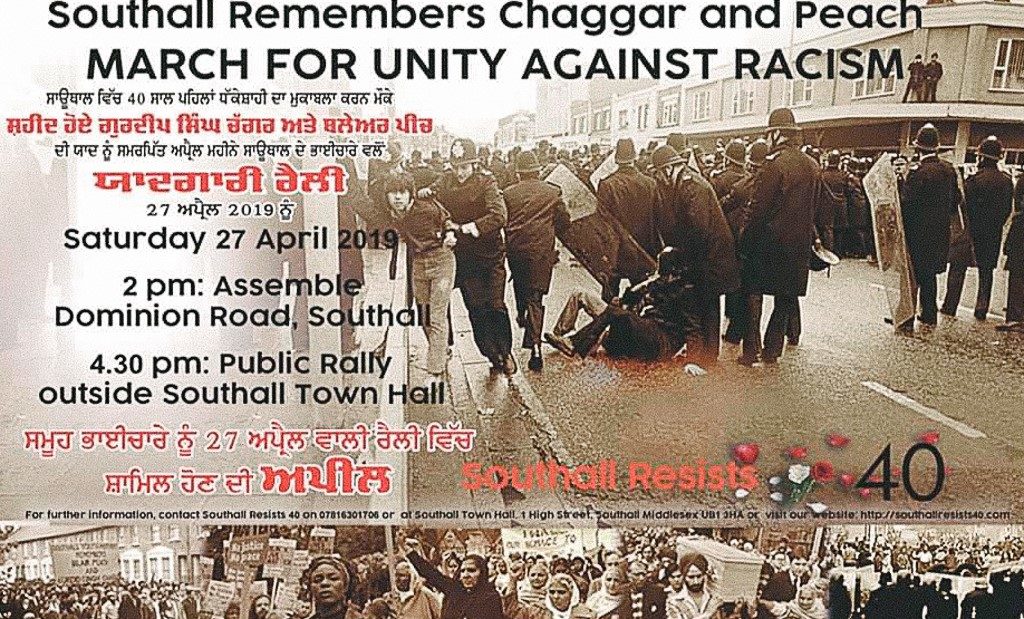

So, as we approach, Tuesday 23 April 2019, the 40th anniversary of the murder of a teacher and anti-racist activist, Blair Peach what and how we remember the past is being discussed again by the community.

Some individuals and groups have been meeting weekly to discuss past struggles under the name of Southall Resists (SR40). SR40 is a coordinating group, comprised of local residents, organisations, activists and artists who are seeking both to pay tribute to the past, but also to think about how to use this to build a foundation for the next generation. If you attend the meetings, one is struck both by the continuing, and persistent symbolic and material effects of the violence from the original event inflicted on their friends and family, but also connect this past to events in the present, such as the killings in New Zealand.

Some collective memories are not just significant locally, but globally, the events of 23rd April 1979 are one such global event, and the discussion from SR40 will hopefully result in a permanent memorial worthy of Southall.

Jagdish Patel is a Nottingham based artist, writer and researcher working in London and the Midlands. He previously worked with the anti-racist group, The Monitoring Group for many years and continues to research and write on issues relating to race, communities, policing, art and Black and Asian history.

Images Credits:

Image 1: Poster from April 1979 produced by Indian Workers Association @IWA

Image 2: Poster from benefit concert held to support Peoples Unite Centre

Image 3: Eve and Oliver Turner @Jagdish Patel

Image 4: Balraj Purewal @Jagdish Patel

Image 5: Vishnu Sharma @IWA

Image 6: Mrs Lakhbir Bains @Jagdish Patel

Image 7: Avtar Brah @Jagdish Patel

Image 8: The funeral of Gurdip Singh Chagger @ Archives of Chagger family

Image 9: Suresh Grover with friend at Chagger’s murder scene, June 1976 @ Archives of Chagger family

Image 10: News of the World, 22nd April 1979

Image 11: Balwinder Rana @Jagdish Patel

Image 12: Peter Kennard, Who killed Blair Peach? 1979 @Peter Kennard

Image 13: Clarence Baker @Jagdish Patel

Image 14: Philly K Bhambi @ Jagdish Patel

Image 15: SR 40 @ SR40