Hannah Lewis, Majella Kilkey, Julie Walsh and Louise Ryan

The Brexit vote has plunged EU Nationals resident in the UK into uncertainty. For the first time many face profound feelings of rejection, betrayal and fear for their futures and those of their children and families. Whatever deal is struck during Brexit negotiations regarding the ‘settled status’ of EU nationals, the general trajectory of May’s Conservative Government on citizenship and immigration has been the deliberate and open pursuit of a ‘hostile environment’. The promotion of discrimination through bordering practices that permeate multiple areas of everyday life – housing, health, education, legal support and advocacy, banking services and work – has marginalised all migrants but also any person of colour. The Brexit campaign and vote has shattered the myth of Britain as an open, tolerant society.

EU nationals in the UK featured in the Brexit campaign largely as figures of unwanted immigration. But since the Brexit vote they have been used as a principle ‘bargaining chip’ in negotiations on the UK’s deal to leave the EU. The ‘Citizens Rights Agreement’ published on 8th December 2017 as part of the Brexit negotiations was presented as a major step forward. However, these promises were immediately undermined by David Davis, the Brexit secretary, stating it is ‘not legally binding’. This continues the Government’s track record of making weak promises and being unwilling to deliver security on the rights of EU Nationals resident in the UK. The agreement is therefore unlikely to have altered everyday insecurities and the feelings of rejection and betrayal experienced by ‘the 3 million’ EU nationals resident in the UK.

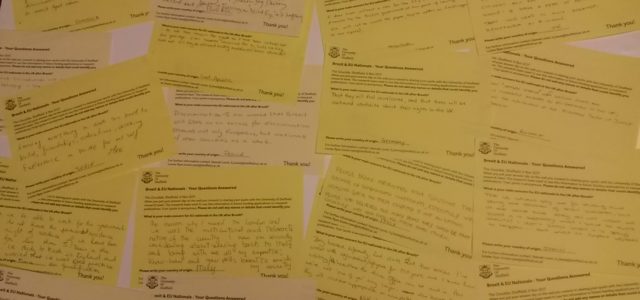

During a recent public Q&A event in Sheffield, on Brexit and the rights of EU nationals, as part of the ESRC funded Festival of Social Science, we collected the views of 37 EU nationals, from 14 countries. It is apparent that feelings of rejection and lack of trust in the government have become entrenched. Attendees voluntarily answered the question ‘What is your main concern for EU Nationals in the UK after Brexit?’. Here, we highlight their views, and points raised about the socio-legal status of EU Nationals during the Q&A discussion with three immigration lawyers, a senior advisor from Sheffield Citizens’ Advice, a Sheffield City Council cohesion, migration and diversity manager, and a Roma rights activist.

The discussion and attendee responses conveyed a palpable sense of a sudden, profound precarity manufactured by the tone of the Brexit campaign, the vote to leave, and subsequent tenor of UK government statements on the rights of EU nationals. These are summarised in the comment, ‘It feels like being a floating log in the middle of the ocean. I guess uncertainty is my biggest concern’ (no country given). Notably, while the anti-immigration elements in the campaign provoked anxiety about the social and economic effects of arrivals from the ‘new’ accession (A8 and A2) countries, ‘old’ Europeans from Spain, Germany, the Netherlands and Italy were prominent among our participants. Someone from Germany, who had ‘lived in and contributed to’ the UK for nearly 30 years said that after the Brexit vote they now feel ‘like a visitor’.

National statistics show a spike in hate crime during the EU referendum campaign, sustained into the highest ever rates of religious and racial discrimination in post-Brexit vote Britain. At the event, this was affirmed in testimonials of incidents of xenophobic street hostility. One woman was particularly upset that she was subject to such abuse in front of a queue of people at the bus stop, who said nothing. For her, the Brexit vote ‘lifted the lid’ on xenophobic racism usually concealed in the UK. In addition to the fear of being the target of discrimination, there was anxiety about a degradation of tolerance in wider society, triggered by the vote and Brexit process. Some feared unfair treatment in employment – ‘My main concern is employment and potential discrimination’ (Slovenia) – others showed concern for their immediate safety – ‘Brexit could promote physical, emotional and psychological abuse to my daughters, husband and myself. It represents a threat to consider UK my home’. (Spain) – and more broadly, some expressed a worry that ‘Brexit will work as an excuse for discrimination towards not only Europeans, but nationals of other countries as a whole’ (Poland).

Hand-in-hand with a fear of direct abuse were more profound statements regarding identity and feelings of belonging in post-Brexit-vote Britain. An attendee from the Netherlands, for example, who had ‘lived in the UK since age of 9’ said, ‘now we’re not one of you any longer’ (Netherlands). Another person showed concern that ‘that EU Nationals will no longer feel a sense of belonging in the UK’ (Ireland). Beyond generally feeling unwelcome, a Spanish participant also indicated that the Brexit vote had left them feeling valued only for their economic contribution: ‘The UK citizens pay me for studying and being the teacher of their children, but at the same time they do not want me’ (Spain)

Fear of losing individual rights and freedoms was coupled with a broader concern about losing the protections of the EU legal tier: ‘I fear that, without a role for the ECJ post-Brexit, the promises by the British government at the point of leaving the EU will not be worth the paper they’re written on (with regards to our rights)’ (Netherlands). Although EU nationals’ rights have not technically changed yet, these profound expressions of betrayal, loss, and insecurity, convey that life before the Brexit vote, at least for some, had been one where EU nationals could live and work in the UK, create families, and build careers, leading to long term settlement. The Brexit vote has abruptly ‘pulled the rug’ from underneath the feet of EU nationals in the UK, their partners, families, children and workplaces and, ‘people who believed for many years they could be part of this country [who] now find all their hopes stolen’ (Italy).

There have been indications that EU nationals are already voting with their feet by leaving the UK. Attendees at the event made it clear, however, that ‘return’ was not necessarily an option:

‘Moving back to one’s home country is by no means straightforward due to housing issues, finding qualified work, getting into health insurance, transfer savings without double taxation, etc. Staying in the UK is not straightforward either, so we are caught in some sort of limbo of indefinite duration’ (Germany)

Those that have previously thought of the UK as ‘home’ have been left in an almost impossible situation, resulting in a painful, liminal state.

Despite the Citizens Rights Agreement, EU nationals are likely to continue to be concerned about practical arrangements for formalising their status. The Q&A highlighted considerable concern about how the Home Office will cope with potentially more than three million applications for ‘settled status’. Despite assurances from the Immigration Minister, Brendan Lewis, history indicates that the existence of a widely acknowledged ‘culture of disbelief’ within the Home Office will lead to refusals, family break up, denial of basic rights and crushed dreams. From the first statement on the rights of EU Nationals in the UK, the phrase ‘legally here’ has been prominent. The Citizens Rights Agreement clarifies that the cut-off date for being ‘legally here’ will be Brexit Day, rather than Referendum Day – the government’s initial proposal. The ‘legally here’ proviso is, however, a line in the sand that adds to the armoury of the Home Office in producing an ever growing population of ‘undocumented’ (or ‘semi-compliant’) migrants in the UK whose position in terms of the vital three strands of socio-legal status (residence, welfare and work) do not line up. This will leave some more vulnerable than others.

Unequal care responsibilities now extend to the emotional and practical labour of securing EU nationals’ family rights and wellbeing. The maintenance of their nuclear family was as a clear theme highlighted by attendees at the event: ‘will my Canadian husband be able to stay as a family member if he is self employed?’ (Hungary) and ‘I have been naturalized… I am… concerned for my kids as they have not. Will they be allowed to stay and finish their studies?’ Interestingly and unusually, at the Sheffield Q&A event, the vast majority of those asking detailed technical questions were also women.

In highlighting the fears and anxieties of EU nationals about their current and future rights, we do not wish to convey any sense that EU mobility pre-Brexit vote was unproblematic. There have always been restrictions and limitations felt and experienced differently in relation to country of origin, migration history, class, gender, ‘race’, and so on. While EU mobility has always benefited some groups more than others, it is also clear that the Brexit vote will categorically diminish the rights and position of all EU nationals’ in the UK (and those of UK nationals living or wanting to live in other EU countries).

The Brexit process will reproduce ever more complex immigration rules and controls. This is likely to lead to increasing irregularity and clandestine forms of entry and stay. As one attendee from Slovakia noted, Brexit could produce a future of increased ‘people trafficking and modern day slavery’. This is far from the picture leading Brexiteers wanted to promote of the possibilities for immigration control and reduction in ‘undesirable’ immigrants within the UK offered by leaving the EU.

Hannah Lewis is Vice Chancellor’s Fellow in Sociological Studies at the University of Sheffield. She is co-author of Precarious Lives. She tweets in a personal capacity @drhjlewis Majella Kilkey is Reader in Social Policy in Sociological Studies at the University of Sheffield, where she co-directs the Migration Research Group – @SheffieldMRG Professor Louise Ryan is a professorial fellow in the Department of Sociological Studies and Co director of Migration Research Group at university of Sheffield. She has been researching intra- EU mobility for almost two decades. Julie Walsh is a Research Associate in Sociological Studies at the University of Sheffield with an interest in family and migration. She tweets in a personal capacity @JCWalsh5