Ingo Gunther

When 5-year-old Bernie Krisher was taken by his parents on a ‘vacation’ to France in the wake of increasing violence in Germany, little did he know that authoritarianism would form the bookends of his life. The years-long journey that began just before 1938 took him and his parents to Paris, then Portugal and eventually ended in Queens, NYC in 1941, where he started his first newspaper at age 12. Journalism was his calling and it became the story his life. Mr Krisher’s latest chapter and likely most lasting achievement, The Cambodia Daily, got kneecapped and then executed in September. The authorities in Cambodia decided that they would no longer be willing to put up with the newspaper that Krisher had founded (and financed) in 1993. After printing 7,500 issues (6 days a week over the last 24 years) it is dead.

In 1993, the Japanese-led UNTAC mission (United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia) had given birth to the world’s newest democracy, crafted hastily out of what was left of Cambodia after two decades of war and civil strife and one of the greatest atrocities in modern history, an autogenocide that killed over two million Cambodians. As a holocaust survivor, who was acutely attuned to persecution and its victims, Mr Krisher immediately saw not just an opportunity but also a moral obligation to bring the so called Fourth Estate to Cambodia – exactly at this time.

He helped, too, with building schools (well over 500 at this point), orphanages, and hospitals that were critically needed. But the paper he founded in the ruins of Phnom Penh was the most unlikely and the most effective contribution he could have possibly made to the success of the country. The initially meager A4 formatted paper (so it could be copied or faxed) that never exceeded more than a 5,000 copy print run, turned out to be the definitive journalism school for hundreds of young Khmer and Western reporters who cut their teeth under Krisher’s very caring and protective as well as demanding and occasionally heavy-handed (micro-) management. More than one Pulitzer prize-winning writer graduated from The Cambodia Daily.

Rather than confronting authoritarianism, making accusations and leading an ideological battle in the name of freedom – Krisher became an expert in dealing with the realities on the ground, working with systems (or the lack thereof) that would frustrate and bog down most anybody else trying to help. Krisher himself was not immune to the appeal of a strong centralized government, one that he hoped to be a benevolent “dictatorship”. He saw this successfully played out in Singapore, arguably to the benefit of its citizens. He said he learned all about the way government works while covering New York City hall for the New York Herald Tribune in the 1950s.

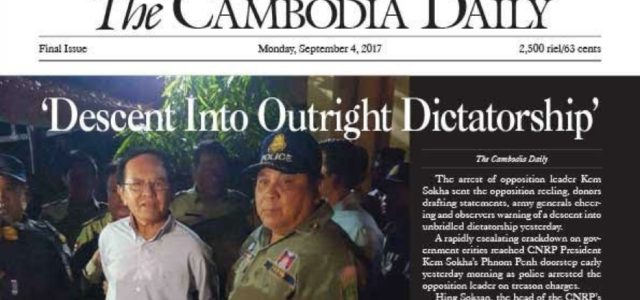

Cambodia has enjoyed a moderate but measurable improvement over the last few years in terms of income, reforms and even personal freedoms. For a few years it was considered ‘freer’ in expression than Thailand or Vietnam. Last year the political opposition parties merged and became a real threat to the ruling Cambodian People’s Party. The opposition’s success in this year’s local elections rang the alarm bells and a somewhat predictable crackdown began. One former head of the opposition in exile was sentenced in absentia; his successor, Kem Sokha, was arrested on treason charges just this month, his arrest making the front-page of The Cambodia Daily’s very last issue.

What on the surface appears like a sudden ham-fisted attempt to silence dissent is also the result of new economic realities. (The paper was presented with a USD 6 million retroactive tax bill and given mere days to pay or face asset forfeiture and prosecution). Western countries had poured millions into Cambodia since the early 90s. A ragtag army of NGOs and official foreign development aid as well as investments have provided an essential kickstart after two decades of war and civil strife. But that influx of money has been dwindling recently.

Following the current American policy trend (termed G–Zero by political scientist Ian Bremmer) the withdrawal of American financial presence and leadership has been felt in Cambodia. Aid contributions would be slashed 70% from 77 to 23 million, and the roughly $43 million of yearly development aid was to be cut to zero in 2018 according to a document that became widely known this April. Shortly after this came to light, Cambodia cancelled joint military exercises with US forces for 2017 and subsequent years.

It probably does not help matters that the U.S. government is unwilling to write off a loan that the US installed Lon Nol Government was forced to take during the Vietnam war as 2.75 million tons of American ordnance dropped on the Cambodian countryside and sent the rural population fleeing to the cities that quickly ran out of food. The original US $274 million ‘loan’ has mushroomed to over half a billion today, including interest and late fees. The U.S., while lending a hand with demining and removing unexploded bombs, has not offered any restitution for the carpet bombings and the thousands killed.

What was once a country at the very bottom of the economic and development ranking has, despite persisting problems, grown over the last few years at a very steady rate of 7%. On the surface it almost appears as if America and China had coordinated their actions in Cambodia. As American engagement has retreated, China, already the largest investor since 2010, has increased its investments and loans. It is now by far the largest donor and investor in the country, its billions eclipsing all other countries’ cumulative investments.

The often critical and investigative-oriented Cambodia Daily newspaper was tolerated by the ruling party at least in part as a demonstration to the international community that there is no censorship. The new Chinese money does not come with such strings attached. The fig leaf of a free press is no longer required. Cambodia’s strongman Hun Sen has wasted no time to praise and quote President Trump’s disdain for the media and vowed to “crush” media entities that endanger the “peace and security” of the kingdom, calling on all “foreign agents” to self-censor or be shut down.

China seems to be equally satisfied with what they get in return: A de-facto veto in all ASEAN affairs ever since the massive investments in 2012. Controlling Phnom Penh de-fanged ASEAN’s collective bargaining power. All disagreements with China will have to be resolved bilaterally, especially those maritime disputes in the South China Sea. This is clearly the end of an era. It is also the end of an era where printed newspapers played a central role for the rule of law in civic society and government in a democracy.

The Cambodia Daily never took money from any government and was as independent as a paper can possibly be. However, the dependence on advertising income also made it vulnerable. When Hun Sen publicly defamed the paper as “chief thief”, he sent a thinly veiled threat to advertisers: if you support the Cambodia Daily, we may come after you as well. The now out-of-work journalists and reporters have been advised that, should they continue to report for foreign media from inside Cambodia, they might be considered spies, facing legal action. It appears that this is the end of independent journalism in Cambodia.

As if to add insult to injury or incompetence to injustice, Mr Krisher’s charitable organizations, now run by his daughter Deborah, saw their accounts frozen as well. The authorities have thus either intentionally or by sheer incompetence also managed to shut down the strictly separated philanthropic foundations that Mr. Krisher has started over 20 years ago. All the while, the tax authorities are claiming that the accounts of Japan Relief for Cambodia and World Assistance to Cambodia were not frozen. The majority of the NGO’s 120 staff has had to be furloughed, school construction has had to be stopped, English teaching in 90 schools was suspended, and the orphanage for 40 children can operate only a few more weeks before it will run out of money. Thousands of students will be affected.

This is the most glaring example of what appears to be a concerted action against anything deemed foreign or critical, especially if associated with the US. Radio stations that would rebroadcast VOA lost their license, several democracy-promoting NGOs were ordered out of the country, even the Peace Corps had been asked to leave. The head of the opposition was arrested on treason charges. Yet almost none of these actions resulted in much more than a news story about the on-going crackdown in the context of an authoritarian regime getting ready to dig in its heels for next years’ national elections.

The closure of The Cambodia Daily, however, stands out, if only by the sheer amount of newspaper and magazine stories that nostalgically recall the challenges, and the adventures, as well as the Daily’s epic success and deeply meaningful impact on the country and those that produced it. The paper had been routinely quoted in the world’s most respected publications for a long time and had earned the right to call itself “The Newspaper of Record”. There has not been a single major international publication that has not written about its recent woe in detail and decried the end of the paper: Foreign Affairs, The Times, The Guardian, the BBC, and even its arch competitor, the Phnom Penh Post, to name but a few. Given the outpouring of grief, sadness, consternation, and anger, one hopes it will only be a matter of time before we see a Hollywood movie about this now legendary defender of the truth and the rule of law.

For now, the Daily is dead and a life’s work of humanitarian ingenuity and goodness is being systematically destroyed. But neither is this story quite yet done, nor are the seeds of independent journalism and competence lost. The echoes of The Cambodia Daily will reverberate in Cambodia and beyond for the future. At least one Khmer alumni of the CD has already publicly expressed hopes for a 2.0 version. It remains to be seen if there is somebody that can fill the mighty shoes of the legendary Mr Krisher in this new era.

Ingo Günther grew up in Germany. He studied Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology at Frankfurt University (1977) and sculpture and media at Kunstakademie, Düsseldorf. After blending sculptural media, journalism through TV, print and the art field he founded the first independent TV station (Kanal X) in former East Germany in 1989 and started the Worldprocessor project that same year, subsequently becoming a founding professor at the Academy of Media Arts in Cologne, professor for media economics at Zurich University of the Arts and visiting professor at the Tokyo University of the Arts and most recently at the Karlsruhe University of Arts and Design. A version of this article in Japanesewas originally published in Foresight magazine, Tokyo.

Image: The Cambodia Daily’s final issue, September 4th, 2017